Rethinking the Campus: Balancing Tradition and Innovation

- Publish On 30 May 2024

- PCA-STREAM

- 15 minutes

At its core, the campus embodies an enduring quest for an ideal. Its form is fraught with tensions inherited from a long history that remain relevant even as it adapts to contemporary challenges. Driven by a race to maximize their appeal, campuses are transforming into architectural showcases, competing with corporate headquarters in embodying new values and attracting top talent. Their structures and functions are evolving to meet the shifting needs of education and society. By embracing the archetypes of the agora and the garden—the original dichotomy of campuses—these bastions of knowledge are forming the contours of a new era in higher education.

The Hellenic Roots of the Campus

The campus form traces its roots back to the very origins of higher education. While Socrates, who is often hailed as the father of Western philosophy, delivered his oral teachings in the heart of the Agora, in the bustling city center, his main disciple, Plato, founded his Academy in 387 BCE in Kolonos, in the suburbs of Athens. This “Platonic garden,” was deliberately kept separate from Athens, providing a dedicated space for teaching and living, where activities included not only research, but sports and cultural events as well. In turn, Aristotle, a former student of the Academy, founded the Lyceum northeast of Athens. In this “peripatetic” school, he dispensed teachings while walking along a planted gallery, within a closed space comprised of various educational buildings and a library. Athens was home to many such teaching “gardens,” one of the most famous being that of Epicurus, located just outside the city en route to the Academy. The Greek model, which was later embraced throughout Europe with the establishment of modern academies, underscores the central role of the garden in the origins of educational spaces, rivaling even classical architecture in importance. It also reveals that, from their very inception, campuses have cultivated a complex relationship between the agora and the garden, and between urban life and nature.

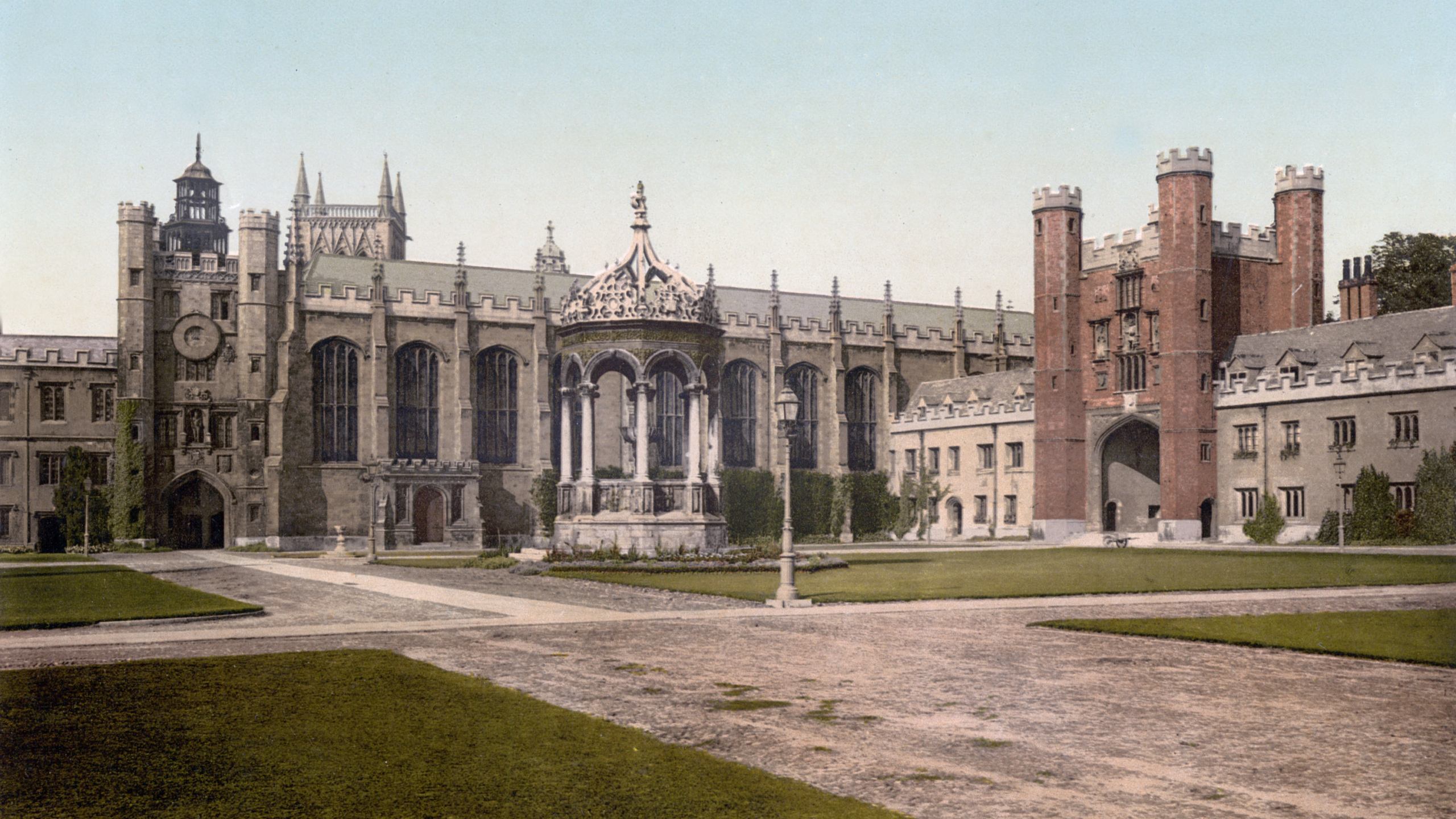

From the English quadrangle to the American campus

Modern campuses appeared in medieval Europe with the creation of the first great universities, in particular the English campuses of Oxford and Cambridge around the 12th century. Students were housed, studied and learned in libraries and museums grouped together on a single, quiet, pleasant site. The buildings are grouped seamlessly around a square courtyard, built on the model of religious cloisters, using a typology known as ‘quadrangles’. There is a close link with nature, but within an enclosed world dedicated to knowledge, as if protected from the outside world, which explains the elitist image projected by English universities.

However, our mental representations of campuses are more largely dominated by the image of the American campus, which is very present in popular culture. Largely inspired by English campuses, American higher education establishments differed from their origins – during the colonial period – from the Oxford or Cambridge model by rejecting the standard of the closed quadrangle. More city-oriented, in contrast to the closed, inward-looking English model, they embodied a desire to make culture accessible and to share it, a desire that would come to full fruition in a new model of their own, with the creation of the University of Virginia, conceived by Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson designed what he called an ‘academic village’ for the University of Virginia, encouraging exchange, enlightenment and collaboration, an environment of collective life where everyone learns from each other, which was to become the model for many of the American campuses that followed him. Driven by a desire for universality, the neo-classical or neo-Palladian ‘Jeffersonian’ style was influenced by the classical architecture he had discovered in Europe, particularly in France during his time as American ambassador in Paris, with the influence of the Château de Marly, for example, in its composition of pavilions scattered around a park, which he preferred to more massive buildings. Initially located outside the city, within a vast green space conducive to reflection, the campus brings together all the needs of students and teachers in a few hectares. Comprising accommodation and teaching spaces in separate buildings, positioned in a U-shape around a central parterre, the campus symbolically places the library in the main axis, with an iconic building topped by a rotunda. Even today, the University of Virginia is regularly voted as the most beautiful American campus, offering a reproducible and replicable stereotype of the ‘American-style’ campus model, based on the quality of the landscape, which has become emblematic in pop culture, particularly in the cinema, almost as a cinematographic and literary genre in itself, with, for example, the ‘campus novels’ by Philip Roth, Jonathan Coe or David Lodge.

The French Reluctance to Campuses

France’s peculiar relationship with the campus form is marked by ambiguity. French campuses often struggle to function effectively as ecosystems for study, life, and work, failing to generate a self-sustaining dynamic. The issue is partly rooted in the historical and symbolic weight of the Latin Quarter in Paris. Acting as a city within a city, the Latin Quarter gradually concentrated an impressive density of elite educational institutions, the grandes écoles, more so with the advent of science and technical schools in the eighteenth century. Yet, despite the encompassing geographical proximity of the Latin Quarter, the institutions and their buildings assert their prestige autonomously within the city.

In the post-World War II reconstruction period, the focus extended beyond rebuilding the universities that were destroyed by the conflict (such as the University of Caen). The democratization of higher education, driven by the increase in student numbers from the baby-boom generation and evolving pedagogy, led to the creation of suburban campuses. This movement was encouraged by pedagogical developments initiated by the Faure Law of November 1968 in the aftermath of the events of May 1968. This law advanced earlier ideas from the post-war period on expanding and democratizing access to higher education, promoting multidisciplinarity, enhanced autonomy, and student participation in university governance. The experimental university center in Vincennes epitomizes the spirit of that era to the extreme.

However, these new campuses have struggled with the persistence of the urban model consisting of adding new buildings within historical complexes and have faced early stigmatization due to their location and architecture. In Paris itself, Édouard Albert’s attempt to create a large modern urban campus in Jussieu has been unpopular due to its brutalist concrete design and isolation, drawing comparisons with the large housing estates that were being built in disconnected suburban areas. Similarly, the University of Nanterre was initially isolated and disconnected from the city where it is located.

French campuses have undergone a succession of development plans, beginning in the early 1990s with the “Université 2000” plan, which led to the establishment of four universities in the “new towns” surrounding Paris—Évry, Cergy, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, and Marne-la-Vallée. This was followed by the U3M plan of the 2000s and Plan Campus in 2009. Although the first suburban campuses of major cities such as Lyon and Bordeaux were eventually connected to the metro or tramway transit systems after a long period of isolation, they still largely lack vibrancy, and relocating to the suburbs is still perceived as a downgrade. The disillusionment with these modern campuses seems to mirror that of the large housing estates of the “new towns,” for similar reasons—the use of low-quality prefabrication systems and concrete, and a considerable lack of green spaces, amenities, and overall urbanity. These campuses leave in their midst a modernist legacy that requires rethinking, akin to the challenges around adapting and preserving twentieth-century built heritage, with its unloved buildings that are often unappreciated, even when they have formal architectural qualities, and, more fundamentally, that have become functionally outdated and unsuitable in terms of energy performance.

A new generation of campuses?

Launched in 2009 and still under construction, the huge science campus on the Saclay plateau is designed as a response to its Anglo-Saxon counterparts, which have a size advantage in the Shanghai international rankings, with the ambition of creating a mixed ecosystem of research and innovation in the spirit of a French-style ‘Sillicon Valley’. Currently ranked 15th in the Shanghai rankings, Saclay brings together the five faculties of the former Université Paris-Sud, an engineering school, four grandes écoles, three technological university institutes, two integrated universities and seven national research bodies, with a total of 48,000 students, 9,000 teachers and research professors and 11,000 technical and administrative staff. Despite these figures, the plateau remains divided into two poles, Paris-Saclay ‘vs’ Polytechnique, and is still perceived as relatively remote and lacking in life. Over and above the overall scientific performance of the campus, which has accumulated results from its various entities, the challenge is to create more synergies around a common culture, embodied in the campus space. Although Pierre Veltz, former president of the public institution in question, felt that the long-term success of the project would depend as much on academic results as on the presence of lively cafés and shops, there is still progress to be made. The fault lies in the fact that the buildings were designed independently, isolated and, like the institutions, had little to do with each other, without creating a public space. As it stands, the physical space of the campus is still failing to create a common spirit. So much so that at the beginning of 2024, the university was placed under provisional administration after failing to vote on its governance, mainly due to differences of opinion with those in favour of a ‘federal’ model between the schools.

In a mirror image, the Condorcet campus in Aubervilliers, Seine-Saint-Denis, aims to become the ‘Saclay of the social sciences’ by bringing together eleven Parisian social science research establishments on a former industrial wasteland. Here again, the aim is to contribute to the international reputation of the French social sciences, which had their heyday in the 1970s, by breaking down barriers and encouraging serendipity and proximity between laboratories. In this respect, the very shape and size of the campus contributes to greater interaction between players and disciplines by offering a greater variety of spaces than the historic Parisian premises, meeting rooms and convivial areas where people can meet and exchange ideas. The campus is completed by the GED, the Grand Equipement Documentaire, designed to provide a link between the various research establishments on site, but also with the local fabric and its historically working-class population. It brings together a large library, a bookshop and a café open to the street, as well as work and social rooms, and makes use of the exterior, deliberately creating public space and developing a large interior street.

The challenge for this new campus remains to ensure that it is territorially integrated and dynamic in terms of activity. Symptomatically, there was an initial rebellion from professors at EHESS and the Sorbonne, who saw the move as a well-known form of university downgrading. However, the context seems radically different from previous exurbanisation strategies, in the sense that a campus like Condorcet now embodies the hopes and dynamics of Greater Paris, of which it was conceived as a showcase. We therefore hypothesise that, for both Saclay and Condorcet, we are facing a new generation of campuses that is seeing an evolution from the paradigm of the periphery to that of a new, broader centrality, but also through a change of referent, where we see them sharing a community of destiny less with the model of the large estate than with that of contemporary innovative workspaces..

Competition challenges

As with the office, the very notion of the raison d’être of ‘face-to-face’ higher education, and therefore of its spaces, has been called into question by the widespread use of digital tools, particularly video-conferencing devices popularised by the Covid pandemic. It is a sign of the times that higher education institutions are now competing with businesses, both economically and scientifically, to attract their customers/students, just as businesses are struggling to attract and retain talent, in a context of globalisation and international competition for training, highlighted by national and international rankings. This global competition is reflected in the very names of institutions, which are often evolving towards more standardised, Anglo-Saxon forms, but also in their desire to develop campuses of international quality, to boost their visibility and appeal abroad.

Campuses are taking on a central role in the attractiveness of establishments, pushing towards iconic architecture in the image of corporate head offices, where the symbolic dimension of embodying values has become central. Ideally ‘Instagrammable’, the campus seeks to make a statement, develop a brand image, embody values and create a sense of pride and community. In this respect, it is interesting to note that PSL University – founded in 2010 and granted the status of Grand Établissement in 2022 – which brings together many of the major institutions in the Latin Quarter, still lacks a unique place of embodiment commensurate with its academic prestige, even though the original ambition was to raise the international profile of these institutions.

Responding to the hybridity of career paths

Today’s campuses have all the more in common with the new workspaces designed for innovation in that we are witnessing a trend towards the hybridisation of career paths. In a more complex and unstable world, the educational pathway can no longer be summed up in a given quantity of vertically delivered knowledge, the assimilation of which, sanctioned by a diploma, ensures status and employment. Education is no longer a given stage in life, in a traditionally typified space. The boundaries between company and school, but also between teacher, student and professional, are becoming porous. These discontinuous pathways reflect the changing profile and expectations of a new generation. The traditional student is becoming a learner who no longer receives a lecture but becomes an actor and co-creator of his learning. The on-demand approach, which has become the norm for cultural consumption, is being transposed to educational content to personalise learning paths.

The logic of on demand, which has become the norm in cultural consumption, is transposed to educational content in order to personalise learning paths. However, traditional teaching environments were designed to transmit knowledge in a vertical model, where a knowledgeable teacher inculcates knowledge in a learner on the basis of a hierarchical and subordinate relationship. The education system needs to adapt to these changes. Rethinking the shape and place of the campus offers unique opportunities to link the vertical of the traditional classroom or amphitheatre with the horizontal of the social and informal.

Creating experiential spaces

Another consequence of the general digitalisation of our societies for teaching spaces is that while we are seeing a generational trend towards greater skill with digital tools, at the same time these young students are finding it harder to concentrate and attend lectures. Almost all the grandes écoles are faced with the phenomenon of students deserting their lecture theatres in large numbers. This absenteeism calls into question the content and format of courses, which are necessarily more hybrid, but also the central place taken by community and festive life. In response, the challenge is to rethink hybrid spaces that combine the physical and the digital in buildings that offer a real experience, with a transformation of spaces that mirrors the changes we are seeing in the world of work.

Changes in our society are reflected in the transformation of our workspaces. More than ever before, the workplace must embody the culture of both the institution and the company. It is no longer simply a place of production, but is reinventing itself as a place for sharing and living together, for identifying with the institution and conveying its image. The trend towards hybrid working, a fundamental movement reinforced by the post-pandemic context, means that the physical experience of the office needs to be made more attractive, in the interests of cross-functionality and teamwork. To achieve this, spaces are becoming more diverse, richer, more flexible and more connected. The aim is no longer to accumulate square metres and workstations, but to enrich the user experience, and to pay close attention to the well-being of employees in order to encourage exchange, creativity and innovation. The development of shared spaces responds to the need to work together. Lastly, the office incorporates the environmental issues we are collectively facing, thereby responding to our ecological commitment and the need for employees to find meaning, which is essential to attracting and retaining the best talent.

Combining the digital and the physical, the contemporary campus offers an alternative to the temptation of the all-digital world and its limitations, notably the effects of isolation, a general lack of dynamism and the fatigue inherent in virtual teaching. In this way, dematerialisation does not erase the role of the space, but assigns it a role as a catalyst for community. It naturally helps to prevent students from becoming isolated and must be rethought at all levels to encourage mutual learning through informal group work and all forms of social interaction. The learner can only learn because he or she is in community with other learners, and the same goes for the teacher. Architecture must re-engage the senses and help to bridge the divide between theoretical and practical knowledge, the material and immaterial worlds. In line with the new paradigms of well-being in the workplace, comfort is of paramount importance, in terms of the size of spaces, lighting, acoustics, the quality and adaptability of furniture, using simple, warm solutions, and even the care taken to provide a variety of catering options. With knowledge available online, the differentiating aspect becomes the very experience of the campus for users. It’s about bringing people together in the same place, to develop a shared culture that involves face-to-face learning, and not just in the classroom. In this respect, the campus is an ideal way of combining formal and informal spaces.

Encouraging innovation, serendipity and multidisciplinarity

While digital technology is changing the way we teach and work every day, it is also being amplified by the beginnings of ubiquitous artificial intelligence, which is challenging the very limits of human intelligence. In a world where artificial intelligence automates tasks that can be predicted, the challenge is to encourage the assimilation of different skills, in particular ‘soft skills’, which enable the development of know-how in orchestrating collaborative action. In this context, innovation requires multidisciplinarity and teamwork. The role of the campus is to provide an environment conducive to encouraging multidisciplinarity and welcoming the happy accident of innovation. The campus space must therefore be redesigned to maximise the opportunities for different people and ideas to meet, by multiplying the number of common areas for exchange, work, leisure and informal encounters, right down to the living areas.

This means providing a range of creative and collaborative work spaces that can accommodate different group formats in a variety of configurations. Even ‘traditional’ classrooms need to offer a greater granularity of possible formats. They lend themselves to active, open exchanges and are modular, so that learners can shape their workspaces themselves. A coherent and innovative ecosystem is created by the furniture and the possible multiplicity of spatial arrangements, as much as by the technology. Multi-purpose spaces that promote well-being, flexibility and generosity, reproducing urban vitality, but also introspection, in order to vary the intensity of work.

In addition to its potential for flexibility, the campus must create new porosities with society through incubators, innovation centres, learning centres and other mixed reception areas that are more open to the city and businesses. Located at the centre of the campus of the Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, the Rolex Learning Center is a space dedicated to knowledge, a library and a place for cultural exchange. It is open to both students and the general public, offering services, libraries, information centres, social spaces, study areas, restaurants, cafés and high-quality outdoor areas. Aalto University in Finland, for its part, has created a ‘university of innovation’ by merging three existing institutions (a design school, a business school and an engineering school) and moving them to a single campus, financed by both public and private funds, where cross-disciplinary curricula, an entrepreneurial spirit and learning through prototyping are encouraged. Finally, we are seeing the emergence of resolutely hybrid models such as IXcampus, which houses CY école de design in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, around the grounds of the Château Saint-Leger, alongside an ecosystem of around fifteen start-ups.

Addressing environmental challenge

With global climate change, we are collectively faced with the challenge of a transition that preserves the Earth’s habitability. For higher education institutions, this means training a new generation of responsible citizens. Students want to contribute to a better world, they feel responsible for it and expect their school or university to prepare them for a career in line with their convictions. This represents an almost existential challenge for higher education establishments, which must meet these expectations if they wish to remain attractive and continue to train the talents of future generations. The more students are trained, the more they acquire the keys to understanding the mechanisms of life and the limits of the planet, the stronger their demands. Students and graduates of the leading engineering schools were among the first and most vocal in expressing the need for more ambitious training. This is borne out, for example, by the response to the famous speech by the graduates of AgroParisTech, or the equally emblematic protests against Total’s plan – finally abandoned – to set up a research centre on the Polytechnique campus at Saclay, but more generally and more quietly by the phenomenon of so-called ‘bifurcated’ students.

Faced with this challenge of responsibility, today’s campuses are faced with the challenge of adapting spaces that were not originally intended for this purpose, by renovating a heritage that is both classic and modern without betraying it. In addition to the need to upgrade the energy performance of buildings, architecture by its very nature always has an educational function, and the space itself must contribute to the body of environmental teaching. Both indoors and outdoors, campuses offer students and teachers opportunities to learn about the natural world: building design provides information on how to use resources, while the relationship with nature on campuses can be placed at the heart of the experience, as a place to live, teach and directly experience a relationship with living things, going beyond the somewhat manicured and decorative dimension of the vegetation on American campuses. This sensory quality is particularly noticeable in the integration of nature via the garden spaces. They enable a reconnection with the living world and provide a new quality of life, while responding to environmental issues in a way that inspires virtuous behaviour. Learning from and in nature is becoming a core strength of campuses

The new Artillerie campus, which is home to SciencePo in the heart of Paris, is a mixed-use, urban-intensity campus that includes an iconic pavilion dedicated to social life, as well as a ‘knowledge garden’ and a number of outdoor courtyards reminiscent of the ancient Athenian garden. On the Condorcet Campus, the project to build six new buildings, initially planned to encroach on the site’s green spaces, provoked an outcry from researchers and students alike, who emphasised the importance of these biodiversity reserves as places where campus users and local residents could enjoy each other’s company, all the more so in an underprivileged area that has historically been particularly mineral.

One of the keys to adapting educational campuses lies in a new paradigm of use, in the spirit of innovative contemporary workspaces, but also a re-reading of the original dialectic between agora and garden. The campus is based on a scale, a typology and a unity of place that gives it its strength, halfway between the built, the urban and the natural. This is the case, for example, of the CY campus project, the former university of Cergy Pontoise, which seeks to reinforce the campus effect within the city, which suffers from its new town dimension, notably due to a lack of centrality. Here, university renewal and urban regeneration are being considered together. The project is based on linking up the scattered establishments and improving their integration into the city, as well as enhancing the quality of life, using the 8-hectare François-Mitterrand park as a structuring axis. These various initiatives, among many others, are the sign of a general movement that we suspect and hope will be fruitful, inviting us to go beyond the traditional dichotomy between urban campus and garden campus by hybridizing the figures of the agora and the garden.

François Collet, Editorial Director at PCA-STREAM