Beyond Singular Intelligence

- Publish On 7 October 2021

- Agnieszka Kurant

- 11 minutes

By experimenting with forms of collective intelligence in her work, Agniezska Kurant fosters the emergence of novel forms based on a multitude of interactions between agents. She thus “metabolizes” the production processes of the living and calls for complex, hybrid, and collective works that are never complete, continue evolving in real time, and involve a “polyphony of agencies.” By setting up processes she intentionally loses control over, and working with AI, geological, or living processes, her works break free from fixed and stable forms.

Agnieszka, rather than producing static forms, you set up networks. The first thing I see in your works are their structure, made of multiple agents who interacted with you. There is always a multiplicity of interventions gathering to a point: the artwork. Why do you insist on collective intelligence, or co-activity, at the center of your practice?

I started experimenting with collective intelligence to undermine the paradigm of individual, singular intelligence and of creativity understood as an individual process, as well as the concept of fixed stable forms. Collective intelligence is always in motion so it can never be fully captured, it is an object in flux. I was also investigating the new kind of extractivism: the ways in which the 21st century digital economy developed systems of value extraction from the collective intelligence of the entire society and from every currently accessible part of the universe. In the post-digital world the so-called “third nature“, as McKenzie Wark recently named it, treats every possible future state of nature as well as synthetic nature as quantifiable, computable and configurable resources. These possible futures can be calculated, hedged, simulated, valorized and monetized.

What first struck me in the phenomenon of collective intelligence, which I started investigating about 13 years ago, was the fact that it disrupts some fundamental concepts in philosophy and anthropology. It produces an ontological shift based on questioning of the notion of the human as an individual intelligence. Today we realize that the contemporary human is in fact an assemblage, a multitude, or a polyphony of simultaneously operating agencies and intelligences, from microbes and viruses to AI. Bacteria and viruses are necessary actors in our immune system and our microbiome impacts our mental states and all decisions that we make. At the same time our decision-making processes are automated and optimized by corporations through algorithmic data mining. In a way we are being hacked both from the inside—by microbes and viruses —and from the outside — by algorithms. As a result, the concept of the “self” as a singular, autonomous individual begins to collapse. It is not a single “self” but various forms of plural subjectivity. On the other hand, it turns out that intelligence can exist without central control or without a unified subject, without a unified self. For example, the slime mold is an example of nonintentional sentience —a form of collective intelligence. Slime mold can solve a complex maze despite the fact that it has no brain and no nervous system.

Science has proven in many different ways that intelligence is never individual, but always distributed. Some cognitive scientists, such as Andy Clarke, talk about the extended mind. And the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio traces the basis of human feelings and conscious minds to the exchanges of chemical signals in the collective intelligence of bacterial colonies at the inception of life. Around 2008 my research brought me to complexity science, which is a field studying complex systems and among others, the phenomena of collective intelligence and emergence. Collective intelligence basically means a group intelligence, where novel forms emerge in nonlinear and unpredictable ways from interactions between thousands or millions of elements or agents or molecules in a complex system. It can be observed for example in slime molds, termite colonies, the internet, social movements, the stock exchange, cities, and in our brains. Complex phenomena such as hurricanes, consciousness or inception of life are products of emergence —a property of collective intelligence, which is based on self-organization. This spontaneous self-organization exists in both physical and social systems: from the living systems and geology, to economy and AI. Complexity science discovered that groups of organisms such as termites, or bacteria, or social movements display diverse personality traits as super organisms or “collective persons.” Groups may have minds in much the same way that individuals have minds.

One of my areas of research is futurity and the evolution of culture. I am trying to imagine in which direction we are currently evolving as a species. Since culture and art can be seen as evolutionary adaptations so with the current transformations of the human in response to rapid technological, social and climate changes art might evolve into something else in the future, into a different evolutionary adaptation. And some aspects of this evolution of culture can be perceived already today. If we look at Wikipedia or Reddit and the circulation of internet memes and crowdsourcing, we realize that they resemble the ways in which knowledge and creativity functioned a few thousand years ago when the Bible and the mythologies were created over the millennia by generations of anonymous authors, by entire societies. Creativity and the production of culture can be seen as the labor of the multitude, and not of single individuals.

It seems that contemporary culture is slowly evolving into that direction again, although it might bifurcate at some point in a completely unexpected way. The current form of artmaking primes individual authors, but culture might evolve into different, more complex, hybrid, collective forms involving not only multitudes of humans but also machines, minerals, living organisms and viruses. A polyphony of agencies. That seems like a possible evolutionary change comparable to the advent of writing. I also think that the nature of cultural products might change: in the near future artworks or books may not be considered finished products as artists and writers will be able to continuously change and update them in real time. There will be no fixed forms, which we can actually observe already today with the perpetually evolving technical objects constantly updated by their creators and users.

In many ways today’s technology produces very palpable examples of the concepts of collective agency, such as Marx’s notion of the general intellect, Simondon’s concept of the transindividual, or Antonio Negri’s idea of the labor of the multitude. A lot of contemporary thinkers whose work was important for me, including Manuel de Landa, Bifo Berrardi, Bernard Stiegler, Yuk Hui, Catherine Malabou, Graham Harman or Achille Mbembe see collective intelligence as a truly crucial phenomenon for understanding the contemporary world. Some philosophers, such as Matteo Pasquinelli, describe machine intelligence and AI not as anthropomorphic but as sociomorphic. Machine intelligence essentially mirrors social collective intelligence, and therefore it uses similar mechanisms of social control.

Basically AI, with the use of neural networks, can also be seen as a form of collective intelligence. We could compare an evolutionary algorithm used in AI optimization of tools or synthetic bones, to an evolution of a tool, a meme or a revolution as a product of collective intelligence of an entire society, over time, or an evolution of an organism in its environment. AI is a product of the capitalist economy and the neoliberal ideology based on individualism. And that’s why AI engineers are imposing on us the view of anthropomorphized singular intelligence (including the fear of Singularity). The resources that allowed for this technology to be developed are connected to imperialism and to the modern concept of human exceptionalism, which transpires in the language used by AI engineers and theorists to describe intelligence in general. That paradigm certainly needs to be questioned.

And once the notions of the autonomous, integrated self and individual intelligence and agency start to collapse, we also need to question the idea of creativity as an individual process and the notion of individual, singular authorship.

My recent hologram work – Errorism – presents a simulation of several artworks which I never authored but could potentially create. The artificial intelligence algorithm GPT3 generated a set of descriptions of new works based on the descriptions of my works created to date and the entire corpus of the English language online. The algorithm revealed patterns in my ideas, of which I am not aware and produced the works which were perhaps rejected by my unconscious or the alternative configuration of my work.

The concept of the “author” is to some extend a construct created to appropriate the labor of the multitude and to extract profits from the general intellect. It is a mechanism devised to appropriate value produced in a dispersed and networked creative process. The emergence of the individual author was part of the process of privatization of the commons, privatization of land, water, knowledge, education which turned things held in common into commodities. I tried to analyze this in one of my recent projects —Emergence, which is a conceptual font realized in collaboration with the typographer Radim Pesko. We fused together 26 fonts from the entire history of typography. From the earliest fonts without authors, to fonts owned and licensed by corporations. The first identified font appeared on the Trajan column in ancient Rome. It “crystallized” as a result of the labor of the multitude of thousands of anonymous stone masons. Today Microsoft claims ownership of the Trajan font —the digital version of the font from Trajan column. That font can’t even be bought from Microsoft, it can only be licensed or rented. That shows the long way from the Trajan font as part of the commons, of the common good, like language and writing, to the same font (digitized) as a product owned by a private corporation.

It is especially important to talk about collective intelligence in times when artificial intelligence became an important defining factor in our lives and when the entire humanity is confronted with major collective intelligence phenomena such as the pandemic and the uprisings and protest movements around the globe. Without doubt we are witnessing a planetary scale social experiment of collective intelligence, which might result in a form of plasticity of the social brain or perhaps even some evolutionary change, or an unexpected bifurcation within capitalism.

I was thinking about all these complex phenomena and then I started applying collective intelligence to art production, which allowed me to develop an alternative method of producing forms, based on complexity and on a polyphony of agencies and intelligences. I started to grow or evolve artworks like living organisms or geological formations or new languages, crowdsourced to the collective intelligence of thousands of non-human and human agents, from molecules, to bacteria, to animals, to online workers and protest movements, to AI neural networks. Quite often I’m not working with the form of the artwork but with the molecular composition of matter or with the organization of a system or ecosystem that crystalizes forms. These forms are often unstable and evolving.

The final form of your works is generally determined by informations gathering, but they are very distinct one from another. What about forms? What is the role of forms in your practice, the value you give them?

I try to produce forms, which allude ontological classification. I use forms to encourage the abandonment of any ontologies and to draw attention to a paradigm shift: the distinctions between natural and artificial, sentient and nonsentient, real and synthetic, life and nonlife do not exist or are starting to crumble. All life forms and all inert things, receive, store, and process information. Everything computes: bacteria, fungi, whales, forests, crystals, rocks, seas, planets, stars, galaxies, cities, nations. The whole universe can be seen as a giant information processor and I work a lot with information processing and with aggregation of information and its conversion into matter and energy and into capital. We have to rethink how any forms are created in the world as most of them are not created by individuals but by entire ecosystems or societies. This fact has important economic, ecological and political ramifications.

In order to talk about these questions I developed a way of producing forms which are outsourced or crowdsourced to thousands of nonhuman and human agents. I create assemblages or polyphonies of intelligences and agencies, involving bacteria, animals, viruses, geological processes, synthetic biology, online workers, social movements, AIs, robots, chemical and physical reactions etc as well as processes of profit sharing and redistribution of capital. This leads to the production of hybrid forms oscillating between different states and realms, evolving or dissolving. Between natural occurring formations and sculpture, between real and synthetic processes, between artificial and natural products, between human and nonhuman, between nature and technology, between life and nonlife, between singular and plural subjectivity. Essentially the distinctions and boundaries between these realms have already permanently dissolved.

My works often consist in either identifying or creating systems, which result is emergence or crystallization of forms. I simply set up a system or program and deliberately lose control over the process. I wanted to create an alternative way of producing artworks based on various forms of collective intelligence, collective agency, as an alternative to a single individual author. I started to observe parallels between the ways in which different forms crystallize and emerge in living systems, in geology and in society: a mineral crystalizes in a similar manner to a sign, a tool, a rumor, a currency, a meme, a crowd, a social movement.

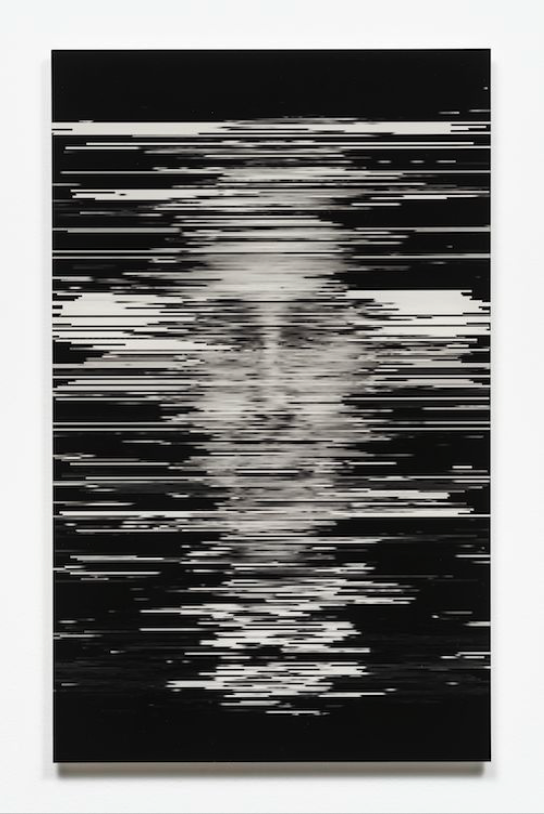

The works such as A.A.I. are built by entire societies —in that case societies of termites. I grow them a bit like geological formations. But each mound form can actually tell us something about the collective personality of that particular society or colony. Each of these natural-artificial mound forms consists of millions of grains of colorful sand, gold and crystals, amalgamated together by millions of living organisms, and the final form is a product of this collective intelligence. My other works are based on amalgamations or aggregations of social capital —for example The End of Signature is an aggregation of thousands of signatures of members of one community or one social movement, fused together by an AI algorithm. Other crowd sourced works such as Assembly Line or Production Line or Aggregated Ghost are based on aggregations of labor of thousands of online workers of the crowdsourcing platforms —the so-called ghost workers, which contribute single lines or selfies that I fused with AI into composite, compound forms. Conversions and Animal Internet use AI to harvest and aggregate emotions or digital footprints of thousands of people around the globe, for example the members of protest movements.

The forms of my works try to capture the fact that objects in the world have no fixed identity, they constantly oscillate between artificial and natural, life and non-life, sentient and non-sentient, synthetic and real, fiction and reality, impossible and probable. What was unthinkable or considered science-fiction yesterday seems very real today. Contemporary science measures the so called “half-life of facts”, the pace at which what we considered as scientific truth is disproved and turns into a fiction. Every single day we are witnessing how objects of knowledge transform, evolve and change their status. My work tries to embody these evolving, unstable objects of analysis of knowledge as they constantly mutate or dissolve. Objects in permanent flux, permanent plasticity or evolution. That is why some of my works physically change their forms in response to changes happening in society.

Both Bernard Stiegler and Yuk Hui, whose writings influenced my work, talked about the emergence of digital objects as assemblages that can be tracked in time and space and they are part of a network of collective intelligence. Digital objects are orientated to the future, constantly in the process of renegotiating their relations with other objects, systems, and users within their milieux, their environment, which is both natural and artificial. They are not able to function on their own without the activities of human beings, who create and modify them. Perhaps in the near future artworks, novels and films will be constantly changed and updated by both their authors and audiences.

On the other hand today we have other concepts of atemporal objects such as the arche-fossils of Quentin Meillasoux or hyperobjects of Timothy Morton. All these concepts try to capture these new phenomena and new hybrid objects with which we are confronted in the 21st century. Objects which are both natural and artificial, living and not, real and synthetic. What is nature if you can easily add a few letters to the DNA of a worm or make a new organism from scratch?

The forms that I’ve been producing try to evoke this oscillation between states, realms and temporalities. Some of these works are both biological, geological and algorithmic, effectively annihilating the boundaries between the human, nature and technology or between natural and artificial and highlighting the obsoleteness of these distinctions. The installation Chemical Garden for example is based on the emergence of new crystalline forms resembling plants from a mixture of inorganic chemicals – salts of metals present in contemporary computers – the industrial extraction of which destroys entire ecosystems and geologies. These exact metal salts generated similar plant structures at the inception of life on Earth. The virtual, the geological and the biological are intertwined.

Some of the forms I worked with recently are connecting changes in society with the physical changes of matter. For example, the digital footprints of thousands of people cause the transformations of physical matter of the Conversions paintings, which perpetually evolve in response to decisions and emotions of people around the globe. Conversions are like living organisms or ecosystems, ever-morphing, evolving, and oscillating between forms. The forms that emerge on the surface of the paintings oscillate between a map, a bacterial colony, a galaxy, the skin of cuttle fish, a geology, the sunspots, or a hyperspectral image from remote sensing. They are between micro and macro scale.

My background is in curating and in philosophy, which has shaped the way I think about forms. My earliest works were conceptual group exhibitions with a multitude of agencies. Over time it became apparent that I was simply interested in various complex and hybrid forms and agencies, and artworks of other artists arranged into a form were only one kind of complex agency that interested me, among many.

Your work Post-Fordite summons archeology, anthropology, geology… I define « molecular anthropology » as « the study of the effects, traces and marks left by human beings on the universe, and on their interactions with non-humans », and your work seems to be a perfect example of it. Why is this molecular level of reality relevant today?

Humans are manipulating matter on the molecular level. We cause rewiring or plasticity of the brain through automation of our decision-making and we cause mutations of biological and geological matter with our emissions and technology. Big corporations are computing and programming both nature and society on the macro and micro scale, on the molecular level. Therefore it was important for me to address these questions with a different work method. The molecular level puts all forms on a par. On the molecular level there is no difference between life and nonlife, between natural and artificial or real and synthetic. When we study the molecular level we see similar patterns and phenomena in nature and in society. And that is the basis of most of my works which are created through amalgamation or aggregation of various molecules, elements or agents: amalgamated capital, labor, signatures, footprints, emotions, agencies or signs. Post-Fordite for example is an amalgamation of aggregated labor of generations of workers who spray-painted cars in now-defunct car factories for 100 years. I combined fragments of Fordite, which is a recently discovered quasi-geological formation created through the fossilization of automotive paint accumulated on car-production lines at factories. Fordite is often used like gemstones to produce jewelry. Post- Fordite relates to the digital footprints, which we all leave in the virtual geology through our online behaviors mined by corporations, which contribute to geological footprints and climate change. The virtual connects to the mineral.

To approach your production method, I used the term metabolization. Metabolism is the series of chemical reactions within a living being. And to metabolize is to incorporate those biochemical reactions. For me, your work is about metabolizing production processes, materializing phenomena which happen in life and embodying them within an artwork. Would you agree with that?

Yes, indeed. What interests me is the fact that metabolism is not limited to living organisms. It circulates and generates new forms in all strata of matter. Organic and inorganic substances are continually reorganized into various forms. And today mineralogists are talking about ‘mineral evolution’ in which the networks of matter and energy flows are connecting living organisms to minerals. So organisms and minerals are no longer clearly separated. This radically changes the field of what is considered life. The installation Chemical Garden explores precisely these relationships of the mineral with the biological and the virtual.

Today there are actually four times more mineral species than before live emerged because life contributes to the formation of most minerals on Earth. Ecosystems are created by the coevolution of minerals with life. And nowadays it is also ourselves who influence the formation of new minerals and geological formations. It fascinates me that the circulation of elements and chemical compounds in some cases creates connections between long-extinct species, the species living today, and species from the future. So the new life forms created by synthetic biology will have an impact on the minerals of the future. After the end of carbon-based life the evolution of minerals will still continue and it will only change its direction. But it is very possible that new forms of matter-energy and non-carbon based life would emerge.

And in my work I am experimenting with hybrid forms that present these diachronic atemporal circulations and fusions, mutations and alchemic transmutations of organisms, minerals and technologies, from the past, present and future. I think about production of natural or social forms as different expressions of matter-energy in flux, along Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the “machinic phylum”. I work with energy as a substance in motion. What interests me is the fact that the contemporary global economy is also based on flows and conversions of energy, which is transformed into information and into capital. Today bitcoin farms are powered by windfarms and water dams which is essentially nature. It is as close as we can get to a perpetual motion machine: free energy generated by nature used to produce value. Of course human labor still exists in these frameworks but turns into hidden, offshore slave labor in coltan mines where minerals for digital devices are being extracted.

The circulation as a form is very interesting to me because networks of matter and energy flows can be observed both in natural and cultural systems. Capitalist economic systems, for example, organize energy and information into market surges and bubbles. The public sphere of social and political mobilization generates crowd forces that are both controllable and unforeseeable. At a still larger scale, the effects of political economies of fossil fuel extraction shape the planet’s geology and the biosphere. I investigate such geo-sociological composite forms based on flows, conversions and metabolisms.

What inspired some of my works such as Conversions is the fact that today, social energies have also to some extent become part of the global energy market. Just as coal, oil and gas are extracted from the natural world, social energies are being mined and precisely quantified by algorithms which harvest data. And my works analyze these flows, conversions and exploitations of social energies in late capitalism, transformations of energy and matter into and out of form. That is why Conversions change and mutate in reaction to what happens in society. I wanted to connect social phenomena with physical transformations of matter, physical metabolisms of the artwork. For the same reason I am sculpting matter on a molecular level to create intentionally produced fossils such as Chemical Garden, Still Life, Fossilized Future or Post-Fordite.

The A.A.I. sculptures are definitely products of metabolization because the millions of termites, which build them use their saliva and feces to glue together the grains of sand, gold and crystals. So the sculptures are the products of the termites’ metabolism. Still Life on the other hand is playing with the “mineral evolution”. It is a synthetic rock that could emerge in the future as a result of a certain sequence of catastrophic events. I used geology as a form of fiction writing. I worked with a geologist to generate synthetic processes to create strata which would emerge as results of events such as nuclear explosions, extinctions of species, disappearance of humans, an impact of a giant meteorite, the death of the sun. I created footprints of events that never happened. I “wrote” these fictional events into the geology and the resulting strata of this synthetic rock are indistinguishable from natural. This rock is both a simulation of the geological future and a materialization or metabolization of human fears.

With A.A.I, you have been collaborating with termites. Is art part of a broader production? More specifically, what could be our relationship, as humans, to animal emissions?

Today animals also became workers. A.A.I. was, among other things, inspired by the ways in which mining corporations use blind, unaware termites to help companies look for new mining locations as termites would always bring to the top any minerals or metals they encounter underground. So the corporations replaced some portion of the slave labor they usually use at the mines with nonhuman labor of the termites. A.A.I is obviously my way of comparing the labor of the bling termite societies building my sculptures to the exploitation of entire human societies, which perform digital, invisible labor for corporations.

Today in a similar manner, thousands of completely unaware animals became digital ghost workers. The phenomenon of Animal Internet identifies the ways in which close to 100.000 of completely unaware, wild animals, are tagged with chips inserted under their skin and then tracked on animal tracker apps, which provides, in aggregate, the data that can allow us to anticipate earthquakes, tsunamis and floods. Tens of thousands of creatures around the globe, including whales, leopards, flamingoes, bats, and snails, are equipped with digital tracking devices and can be followed on animal tracker apps. Data about their behavior is gathered and studied by scientific institutes and is used to predict and prevent phenomena such as volcanic eruptions or epidemics. Elephants in Sri Lanka could warn us about future tsunamis; toads can anticipate earthquakes such as the one in L’Aquila in Italy in 2009; tracking geese’s altitude could forecast large-scale avalanches and an Ebola epidemic could be predicted by fruit bats. This is certainly a paradigm shift in the human understanding and experience of nature through digital means. May people watch nature only on webcams. And these animals which are being filmed unbeknownst to them are having double lives: their wild life and a second life on the computer screens of thousands of people around the world who create websites and facebook pages for these real animals and give them names.

On the other hand, collective intelligence of bacteria helped us develop Crispr so this is certainly another participation of the non-humans in contemporary technology. These involvements of nonhumans in human environmental, political or economic predictions and in new technologies can help understand the collapsing boundary between the human, nature and technology, between the natural and artificial, biological and digital.