Building Consensus on AI-driven Urban Design

- Publish On 7 October 2021

- Kent Larson

- 8 minutes

Though AI is revolutionizing the practice of architecture, it follows the increasing digitalization that has been unfolding since the 1980s. Kent Larson was one of its pioneers. Alongside the City Science research group at MIT, he explores how data can help imagine production processes and innovative forms of urban governance stemming from an evidence-based approach and favoring consensus-building through modeling. He views this holistic approach to the complexity of urban reality as the only one that could bring about genuine change, though it raises the issue of the quality and control of data. He also calls for community databases offering an alternative to surveillance capitalism.

Could you describe the origins of the MIT City Science group and your activity within the laboratory?

The City Science research group at MIT Media Lab is working to bring together the three largely separate worlds of social science, design, and technology with the goal of enabling better cities. All three reflect aspects of my background. Our work to recognize and respond to complex human behavior builds on my interest in anthropology for which i received my first degree. Certainly, design is key to everything we do with my research group, and this reflects my years of practicing architecture in Manhattan. And our efforts to develop useful technology for cities is an extension of the work I began in the late-1980s to explore the transition of the practice of architecture from analog to digital. In those years, I happened to be one of the first architects to experiment with radiosity-based lighting and material simulation for architecture before commercial software was available for this. This journey led me to create a book on what I conceived of as a digital photographic essay on how the unbuilt masterworks of Louis Kahn might have been experienced, followed by several exhibitions, and eventually to an invitation from Bill Mitchell, Dean of the MIT School of Architecture and Planning, to help explore the new and fascinating world of computational design. MIT is, of course, at the center of the universe for technology, and it led the way in developing what we now call IoT, or Internet of Things technology. But rather than focusing on technology embedded in the systems that people use in the city, I was far more interested in leveraging technology to develop novel data-driven, evidence-based city-making processes. Today, we are focused on developing hyperlocal solutions to global problems. Our work is based on the premise that the planet is becoming a network of cities, and that successful cities in the future will evolve into a network of livable, highperformance, entrepreneurial, resilient communities. I believe that to solve our great transnational challenges— from global warming to equity to public health—we need a new model for creating communities that makes use of more sophisticated data-driven processes.

After the shift from analog to computational architecture, we are now experiencing a new evolution from intelligence and machine learning. Do you think social science can help us envision this transition?

Cities can be thought of as places and systems that support complex human activity, and social science is absolutely crucial to better understand what is at play. Different domains impacting cities exist in silos. First of all, there’s the world of politics and public policy, primarily made of governmental entities that focus on such things as tax policy and zoning regulations, and these are largely independent of design and technology. Then you have the world of design— urban planners, architects, and the process of creating master plans for a city. Formally, the design may be highly sophisticated, but the solutions are often simplistic and naive in that they don’t acknowledge the human dynamics of a city in any fundamental way, and indeed rarely take advantage of sophisticated modelling and simulation with respect to human behavior. Finally, there are the thousands of smart city solutions offered by companies that make IoT devices. They argue that by optimizing the flows of vehicles and energy in the city, for example, we can dramatically improve performance. The work in each domain is useful, but in isolation, they have limited impact. These worlds all need to come together in some holistic way. Yet, there are precious few entities trying to unite them so as to lead to meaningful change. Hopefully, this is an area where we can contribute.

Cities are the future—where most of the population growth will take place, most of the wealth and ideas will be created, where the problems are most visible, and where solutions can have the most impact. The question is, can we develop a new approach, a new process for cities that responds to the grand challenges of our era? We delineate five key elements in this process which do not necessarily occur in a linear way, but it can be useful to differentiate them.

We think of the first step in the process as insight, or understanding current conditions. This is where we make use of so-called “big data” to get a fine-grained understanding of economic conditions, demographic profiles of residents, the status of existing infrastructure, flows of energy, CO2 emissions from buildings and vehicles, and knowledge about where people live and work and the mobility modes that take them between places. Collectively, this delineates the urban metabolism, which is defined broadly to include the behavior of humans. Insight is an essential first step, but it is only useful to the degree that it informs the development of interventions. Transformation is the second step, where we ask: How can we identify the interventions that improve social, environmental, and economic conditions? These may include architecture and urban design proposals, and our urban programming work to tune the density, proximity, and diversity of urban components falls into this category. It also may include a variety of new systems, and our efforts to develop lightweight autonomous mobility, compact transformable housing, and soilless food production are examples of emerging systems that could be incorporated. At this stage, there are thousands of possible interventions that could potentially improve the lives of people and solve societal problems, but they are just ideas without the third component: prediction.

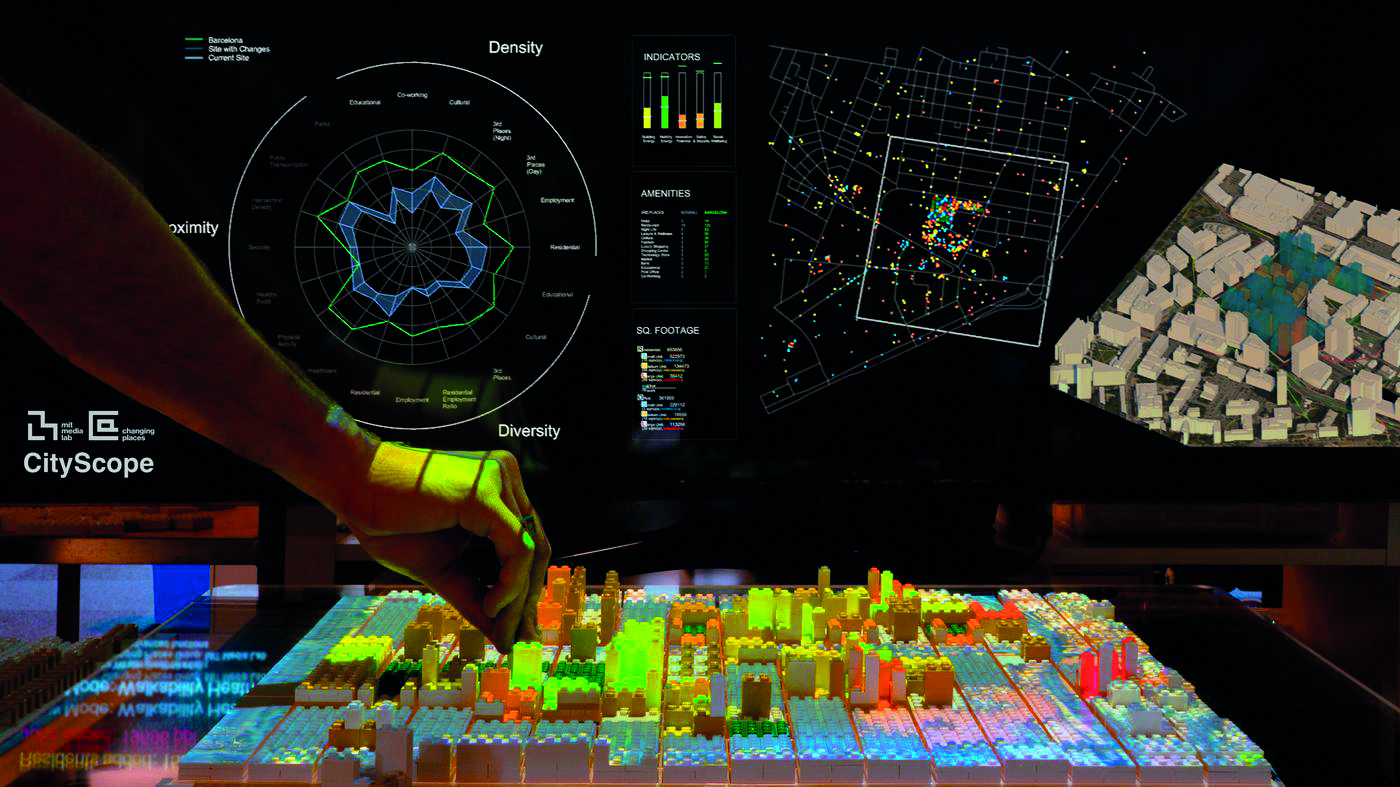

It is a staggering reality that trillions of dollars are invested into urban infrastructure without the benefit of credible predictions of their impact. In this third phase, we ask : How can we develop simulation models that are sophisticated enough to give us confidence that the proposed interventions will have a positive impact ? We are developing the metrics to quantify the social, environmental, and economic performance of a community, and a suite of simulation and agent-based modeling tools to interactively study a range of urban interventions in realtime. Our CityScope platform allows us to interactively visualize scenarios of possible futures.

At this point in the process, we understand current conditions (insight). We have identified the interventions that could improve on those conditions (transformation). And now we have modeled their impact on a community (prediction). But as powerful as this is, a fourth step is required : consensus.

The consensus phase asks the question : How can we bring the stakeholders—the people who live and work in a community, the politicians, the companies that might provide products or services—together to reach a shared vision of their future ? This can be a very complicated process, and many of the best ideas for cities never get implemented due to opposition within the community and a lack of understanding of the impact of proposals. A recent example is Sidewalk Labs’ failed Quayside1 project in Toronto, where the company did not, in my opinion, effectively communicate the value proposition to the community. They did not build trust with the residents, and did not build strong relationships with the authorities in charge of the review and approval process. Building consensus is often key to deploying new and better ideas. I often think of our CityScope platform as a consensus-building machine.

The fifth step of our process involves the deployment of innovations related to governance, where we ask : How can a community deploy dynamic systems that can adapt and evolve over time as economic, technological, and social conditions change? Related to this, we are expanding our scope to investigate how dynamic algorithmic zoning regulations might create incentives for prosocial real estate development, or how local token economies can drive prosocial behavior. In this way, we might achieve a kind of civic homeostasis that is analogous to the predator-prey feedback mechanisms found in natural ecosystems.

And so, in essence, the City Science Initiative is trying to develop each of these key elements of a new model for cities and their communities : insight, transformation, prediction, consensus, and governance.

Regarding these last two phases—consensus and the governance model— ultimately these are very human and socially rooted. Does that mean that the more for urban design, the more human and social interactions you should have to bring in to make sure they are well understood?

These systems are only as good as the people that develop them and the data that is used to drive them— “garbage in, garbage out ” as the cliché goes. AI systems alone aren’t the be-all and end-all, but they can be very useful if they’re developed carefully. Humans are particularly good at certain things : making value judgments, establishing priorities, or identifying creative or unexpected connections between things. Machines are typically terrible at that. Conversely, AI systems are good at doing certain things that humans cannot do well, such as processing vast amounts of information and identifying subtle patterns. AI can be much better at optimization than humans, but creating cities is not an optimization problem.

When you bring together what humans do best with what machines do best, you can create something very powerful. AI is like any other tool, which can ultimately be used constructively or destructively. Ideally, hybrid systems will make use of machine learning intelligence to, for example, present humans with ranked alternatives and carefully presented information at the point of decision to give people more control, rather than less. You might more properly call such AI systems augmented intelligence rather than artificial intelligence. We’re working toward developing such a system.

In the end, it is essential that humans trust this AI technology. Black-box systems, even when fantastic, can potentially represent a step backward when there’s no transparency, and when trust-building isn’t a fundamental aspect of their design. And, as previously mentioned, an AI system is only as good as the data that goes in and the sensitivity and skills of the people who develop the algorithms. There are many examples of AI systems that inadvertently capture the biases and blind spots of their designers, or that make use of unrepresentative training data that skews the results, with unintended and potentially harmful consequences.

Planning and architecture typically involve top-down process controlled by experts who engage in only superficial ways with people in a community about decisions that can profoundly impact their lives. In many cases, this involves a problematic zero-sum game that leads to confusion and conflict. For instance, real estate developers may want to maximize the density of high value uses such as corporate offcies to achieve a higher return on investment. City officials may support increased density that will increase the tax base, but may prefer affordable housing to improve equity. Environmentalists might advocate for parks or lower density in order to maintain the light and air that reaches street level. Existing residents way worry about gentrification, loss of parking, or an increased congestion that often accompanies development. A pet owner might object to a project that eliminates their neighborhood dog park, etc. Ideally, all of these stakeholders with different values and objectives would come together to agree on a shared vision of the future—to discuss, compromise, and search for win-win solutions. In this example, a new and responsive process may reveal to everyone involved that a higher density community, where the supply of housing is in sync with local jobs, may all but eliminate rush hour commuting and traffic congestion. It may create a walkable community with local access to resources, support better restaurants and schools, provide new job opportunities, and increase the creative human interactions and innovation potential that, over time, build community wealth. Machines will never replace this most human of processes, but they can greatly help people reach an informed consensus by providing real-time information and visualizations when and where people need it.

Our CityScope Hamburg project was an early step toward this new process, and a real-world success story. My MIT team and our collaborators at Hafencity University built a platform that was used by the residents of Hamburg to identify sites to build housing for refugees. Mayor Scholz established three very clear and compelling criteria for this project : 1. every district, rich and poor, had to shoulder an equal share; 2. there must be an even assimilation of refugees without a concentration in any location; and 3. the local communities, not the government, would decide where refugee housing was to be built in a bottom-up process. We created a platform that revealed the suitability of various sites, and allowed up to thirty participants at a time from each community to interactively and collectively experiment by moving opticallytagged LEGO modules that represented housing from site to site, receiving computationally generated feedback with respect to access to schools, jobs, mass transit, shopping, etc. This issue of where to build housing for refugees from the war in Syria was emotionally and politically charged, but this process brought out the best in people. Although each person arrived at the workshop with their opinions and prejudices, this transparent and data-driven process empowered those who came to solve a problem, and disempowered those who came to disrupt—just the opposite of a typical open-mic community session. It allowed each community to reach a consensus on which sites would be best suited for refugee housing based on their needs and the values of the existing residents.

I believe that some version of the various platforms that we have prototyped will be used for community consensus building in the future for most urban design projects. Of course, the issues that we explored in Hamburg were fairly focused. More complex projects with many variables make the design of a computational consensus building platform far more challenging. And this is precisely what makes it an excellent MIT research project.

The increasing role of AI in urban design also raises the issues of data standards and governance…

Data is the fuel for all of the systems that we are building, and unfortunately, the data that we most need is not widely available. In the United States, we have a good system for publicly available census data, the National Household Travel Survey, and many other datasets. This provides a good start, but most are only crude snapshots in time with small sample sizes. Many developing countries lack even this limited open data. The unfortunate reality is that the best datasets are locked down by corporations such as Facebook, Google, Amazon, and banks that collect mobile phone location and transaction data for their own commercial purposes, but do not widely share data with researchers, designers, or even with cities for the public good.

I am quite excited about the prospect of creating an alternative to this surveillance capitalism—a new way of capturing data of this quality of the public’s benefit. We are envisioning a community data exchange or data co-op, where people voluntarily contribute their mobile phone location data and other information, which is stored by a trusted entity such as a bank or credit union. People now trust banks to securely store their money, and to restrict access to only those transactions that they approve. Why not do the same with highly personal data? Individuals can establish permissions for who can check out, but not own or sell, properly anonymized data for the benefit of the individual and their community.

We happened to face this problem recently as we were working on the development of contact tracing applications for the pandemic to flag when an infected person might come in contact with non-infected people. It took many months of negotiation with Apple and Google to get access to the information of mobile phones running on iOS and Android and ultimately, due to the complex privacy requirements, it wasn’t even very useful. There is an important societal question we must ask : How can the right people or organizations get access to rich human behavior data, while simultaneously protecting the privacy of the people who generate the data? It is imperative that we find answers to this question, and community data exchanges may offer a partial solution.

How do you envision the evolution of mobility and transportation systems ? Do you think that they are currently undergoing renewal and will reshape the city as they have in the past?

I think that we are now transitioning into the third mobility revolution. The first happened between roughly 1880 and 1920, when trams and subways came into the city. Prior to that, the neighborhoods within cities were compact, and fairly high density. These new systems connected neighborhoods and allowed the city to extend out in linear ways along these rail and subway corridors. The second mobility revolution involved the transition to affordable automobiles after Henry Ford commercialized the low-cost production of vehicles. This started in the early twentieth century, but accelerated after World War II, which saw the suburbans fill in gaps between rail corridors and the surrounding farmland in a low-density, auto-centric manner with zoning ordinances that mandated separated land uses which were only accessible by car. The U.S. led the way in exploring the premise that people could find freedom, autonomy, and opportunity by living where they pleased, with every place connected to every other place by roadways and plentiful free parking.

Many parts of the world are now largely rejecting that model as we recognize its negative impacts, and are returning to the notion of community—as evidenced by the fifteen minute city movement. We see, first of all, an emphasis on improving the functional autonomy of communities, where people have local access to what they need in daily life— schools, shopping, recreation, healthcare, and so on. We also see the dawn of a third mobility revolution, which involves the transition away from top-down centralized systems to much more distributed, lightweight, and ultimately autonomous community-scale systems. I envision a future with mobility systems that have an even greater efficiency than mass transit, with the responsiveness of a ride share model like Uber, and that generate few emissions. In compact communities, walking and biking will be the most important modes of travel. I believe that we will also see an explosion of lightweight autonomous vehicles, such as our three-wheel Persuasive Electric Vehicle or our Autonomous Bicycle that its ridden like a conventional twowheel bicycle, but that converts to a self-driving three-wheeler for autonomous pickup and rebalancing.

Ultimately, I envision new types of ultra-light autonomous vehicles that can pick up individuals at their origin, be tethered digitally to form something like a train to move between districts, and then each unit can branch off as needed and deliver people or goods to specific locations with ease—combining highly responsive mobility that picks you up wherever you are, and delivers you wherever you want to go, but over longer distance mass transit. These systems could be extremely low energy, and could be designed to encourage physical activity.

Going back to the City Science group, it is organized within an international network of laboratories. What is the role of collaborative processes inside this network, and what did you learn about collective intelligence?

I decided about five years ago that we needed to focus on getting our ideas out of the lab and into the world. We do that in two very different ways. First of all, we launch spin-off companies to commercialize work that we feel is ready for prime time. In addition, we have developed an international network of affiliated City Science Labs in Shanghai, Taipei, Ho Chi Minh City, Toronto, Hamburg, Helsinki, Andorra, and Guadalajara.

With our network, we can leverage our efforts and gain intimate knowledge about the unique challenges and opportunities in cities in Asia, North America, Latin America, Europe, and hopefully soon, the Middle East. There are fundamental problems that are common to communities everywhere—food, water, employment, and access to mobility—and there are also endless variations due to the unique locations, history, economies, politics, and culture of each place.

If we’re doing our job well, we can focus on the development of design strategies, technology, and methodologies, while our collaborators can adapt, deploy, test, and evaluate the effectiveness of what we all co-create. We’ve been at this long enough that many of the labs are developing their own innovations that respond more directly to unique needs. Ideally, innovation developed in our lab at Tongji University in Shanghai or Taipei Tech in Taiwan, for example, can be adopted by our newest City Science Labs in Ho Chi Minh City or the University of Guadalajara in Mexico. There are a number of other city networks who share ideas and best practices. We want to go well beyond this by creating a network that shares models, data, code, algorithms, electronics, and design solutions as well. We put these ideas out into the world by using an opensource GitHub repository. The idea is to collectively build the systems that will enable better urban places, and to make open urban innovation freely available to everyone in the network.

(This article was initially published in Stream 05, in 2021)