Cities of Information

- Publish On 19 April 2017

- Carlo Ratti

- 6 minutes

An ever-increasing number of economic and institutional entities have taken up the subject of digital urbanism to conceive and design the smart cities of tomorrow, but also to program the technological shift that affects the cities of today. Spearheading this research is Professor Carlo Ratti, who describes the central role played by information in the development of cities and the way it is redefining their vision, their very nature and their day-to-day operations. He then describes for Stream the urban data processing experiments that his MIT laboratory, the SENSEable Lab, has conducted. These have led to the concept of the “real-time city”, which is equipped with sensors to capture and process data in addition to being characterized by “opportunistic remote sensing” of data that is generated by the behavior of the residents themselves. Managing and inhabiting cities becomes more efficient through this open-source approach.

Carlo Ratti is an architect, founder of the Carlo Ratti Associati design firm. He is a researcher and teaches at the MIT SENSEable City Lab.

Stream : As often in history, we feel that we are living in a new era. But what are the major changes that suggest that we are living in a real “anthropological rupture”?

Carlo Ratti : The profound “rupture,” as you called it, that sets today apart as a new anthropological era, is information. Through new ubiquitous technologies that suffuse urban space, we have developed a capacity not only to gather information, but also to impact the city. This forms a kind of sensing and actuating loop: feedback and response in real time. We have an unprecedented ability to understand and react to the world around us—whether that is the natural world, the built environment, or the social and connective landscapes of human networks.

Open urban data

Stream : Could you explain the idea of a “real-time city”?

Carlo Ratti : The concept of a real-time city is built on two different modes of “sensing” urban space. One is the idea of deploying a large number of sensors to generate a certain dataset—for example, air quality sensors taking measurements in a city. The other, called opportunistic sensing, is to utilize existing systems or devices to gather data—such as mobile phones or social media.

The key to the real-time city idea is that, given one of these sources of data, analytic systems can process and feed back information at the same time as it generated. This ongoing exchange of information will provide us, as planners, engineers, designers, and—most importantly—citizens themselves, with more data. The real-time city will become a platform onto which we can build tools that enable us to design, manage, and live in the city more efficiently.

Stream : We live with a complex set of changes that we sometimes have difficulty understanding: what new models, or conceptual tools do we have to develop in order to understand these mutations?

Carlo Ratti : I agree—these changes are becoming increasingly elaborate and diverse. Yet there is a model for adapting to complex circumstances that has existed for hundreds of thousands of years: open sourcing. Take biology as an example: evolution is a sophisticated means of arriving at the best possible solutions to any condition. Or, in the case of human action, consider vernacular architecture: the way man has always built spaces of habitation, over generations of design-by-trial. Architectural problem solving forms a continuum that delivers a unique structural response to local culture and environment.

In the same way, open sourcing—that is, a model in which the crowd is empowered to contribute acts of design towards the broader complexities of a challenge—could provide us with a comprehensive understanding of “modern mutations,” given its inclusive and collaborative nature.

Next possibilities

Stream : We started from the idea that all these revolutions (globalization, digital technology, general urbanization, environmental crises) changed our relationship to space and time, which must affect our architecture. How would you describe the evolution of the relationship between space and time?

Carlo Ratti : Architecture is only now beginning to become “smart” and responsive—that is, dynamic through both space and time, in tandem with people. Rather than a mute structure for keeping out the elements, it will engage dynamically with its users. One small example is a project we are doing now to address the asymmetry between building occupation and climate control by creating personal climates—a system that could improve energy efficiency by orders of magnitude. Through motion-tracking and infrared lenses, an individual thermal cloud follows each person, ensuring ubiquitous comfort while minimizing overall heat requirements, and ultimately sparking vibrant encounters in physical space as people share their climates. Man no longer seeks heat—heat seeks man. In a broad sense, digital technologies allow us to create and interact with architecture in new ways, on the scale of the building, and to evolve or adapt urban operations on the metropolitan scale.

Stream : Can you describe your work and research at MIT with the SENSEable City Lab? How do sensors lead us to a new approach to the city and to a radical evolution of urban space?

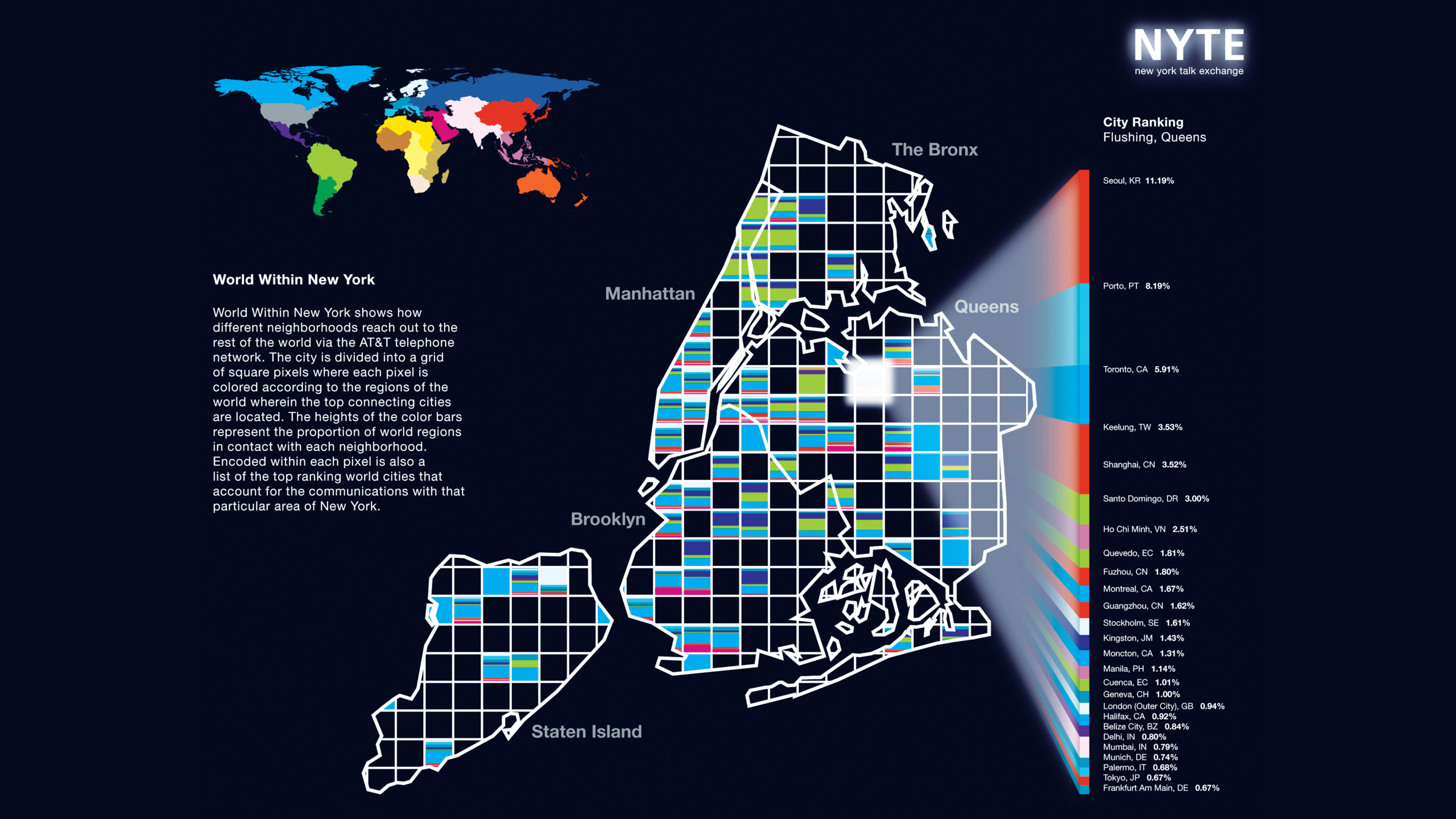

Carlo Ratti : We chose the name SENSEable City Lab to describe our methodology: moving beyond “smart cities,” which imply a city-scale computer. We are more interested in “sensing” the city. To do this, we look at how both active and opportunistic sensing can provide us with a better understanding of the dynamics in our built environment. Urban data can provide citizens with information that empowers them to take better-informed decisions or even to have a role in changing the city around them, which result in more livable urban conditions for all. By investigating and anticipating the changes in the relationship between cities, new technologies and people can work to deliver new solutions, research, or applications, and ultimately address urban challenges through science and design.

Stream : Can you tell us about the singularity and strengths of MIT’s cross-disciplinary work, which seems so crucial today?

Carlo Ratti : It’s simple—our goal is to achieve truly paradigm-disruptive results and to push innovation, whether it is digital, biological, or even participatory, and to create interfaces for people to have an active stake in their built environment. To do that, we bring together a team of talented researchers and designers from a wide spectrum of fields, and create an environment where they can work collaboratively toward a single goal.

Stream : What has changed the most in your architectural practice with this continuous evolution of technology and with the increase of computational power?

Carlo Ratti : New technologies and their increasing computational power are changing the scope of an architect’s role. Until today, architects have thought of static structures, but now we are designing interactions, experiences. Buildings are almost coming alive. When we consider the brief for a new project, we find ourselves with a whole new toolkit of possibilities.

Stream : One hypothesis is that contemporary mutations reactivate the idea of the living, the metabolic metaphor in our approach to the city. This return to nature as a growth model is recurrent in the history of art, but it seems that it has taken on a new dimension with the potential of digital technologies. Do you think this metaphor of a metabolic city has become more relevant?

Carlo Ratti : What has truly changed is the possibility of co-creation within communities—recalling what I said earlier about open-source design, this is the idea of “hacking the city.” Through new modes of connection, design, and fabrication, the process of creating spaces and events has been democratized. This inclusive, almost evolutionary process resembles natural or metabolic growth.

(This article was published in Stream 03 in 2014.)