Coactivity : Notes for The Great Acceleration, Taipei Biennial 2014

- Publish On 19 April 2017

- Nicolas Bourriaud

- 15 minutes

As a prelude to the Taipei Biennial, Nicolas Bourriaud presents a panorama of contemporary art and its transformations in the era of the Anthropocene. The impact of human activities on the Earth system has led us to the geophysical epoch of the Anthropocene. This condition affects our world view and is bringing about new philosophical perceptions on the world, considered in terms of substance, as the speculative realists invite us to do with their holistic school of thought in which human beings, animals, plants and objects must be treated in the same way. This philosophy resonates strongly with contemporary art, as the relationship between biological life and the inert seems to be the main tension within contemporary culture, creating a “space of coactivity” that provides a new meaning to form and gives birth to what he calls “exformes.”

Nicolas Bourriaud is an art historian, art critic, theorist and exhibition curator. Since 2016, he is the director of the future Montpellier Contemporain (MoCo).

Mechanical activity

1. The extent and acceleration of the industrialization of the planet has prompted a number of scientists to hypothesize the advent of a new geophysical era, the Anthropocene. Following the ten thousand years of the Holocene era, this new age reflects the impact of human activity on the terrestrial system: climate change, deforestation, soil pollution—even the structure of the planet has been modified by humankind, whose effects now outweigh any other geological or natural force.

But the idea of the Anthropocene also points up a paradox: as the collective impact of the species becomes more real and more powerful, so the contemporary individual feels less and less capable of having any effect on his or her surrounding reality. This feeling of individual impotence thus goes hand in hand with the massive, measurable effects of the species, while the techno-structure we have generated seems impossible to control. The human scale has collapsed. Powerless before a computerized economic system where decisions are determined by algorithms capable of performing operations at the speed of light (high-frequency trading already accounts for three quarters of financial operations in the United States), human beings have become spectators or victims of their own infrastructure. We are thus witnessing the emergence of an unprecedented political coalition between the individual/citizen and a new underclass: animals, plants, minerals, and the atmosphere, all attacked by a techno-industrial apparatus that is now clearly detached from civil society.

2. Nearly twenty-five years after its public inception, the Internet, though generally considered a tool for freeing information and generating interaction and knowledge, now hosts more machine-driven activity than human activity. Search engines, ad servers, and algorithms used to collect personal data are now the dominant population of a network in which each human user—reduced essentially to the “data” that constitute the main value of his presence for the economic system—is like a hunted animal. Here, it is the individual who is profoundly modified by a massive apparatus, just as natural ecosystems have been.

The modernist art of the twentieth century took on mechanical and industrial processes, either as a motif (Picabia, Duchamp) or as a material (Moholy-Nagy, Tinguely). Today, technology is seen as one “other” among others, one more subject that abusively considers itself as the center of the world. And artists live at the heart of the technosphere, as if in a second ecosystem, putting search engines and living cells, minerals, and artworks, all on the same utilitarian level. What matters most to artists today is not things in themselves but the networks that distribute them and link them together.

Ghoslty round

3. In Das Kapital, Karl Marx formulated a strange image, that of “goblin tricks,” which may well represent the symbolic essence of capitalism: a concrete element, the social relations of production, is reduced to an abstraction; and, conversely, the abstract (the exchange value) is transformed into something concrete. Thus, human beings actually live in an abstract world, that of exchange and capital flows, and, at the same time, experience the concrete world of work as an abstraction in which they turn out to be interchangeable. Such is are the goblin tricks described by Marx: inanimate things start to dance like specters, while humans become the ghosts of themselves. Subjects become objects and objects, subjects; things become persons and relations of production are reified.

In these early years of the twenty-first century, a period we could describe as the Political Anthropocene, these goblin tricks concern not only persons and things in a relationship of industrial production, but also the subjects of the global economy and planetary environment as part of an even more spectacular reversal: the immaterial economy is taking over concrete geophysics, and the material planet is being transformed into a sub-product of the abstraction of capital. In an earlier stage of the capitalist system, when he was discovering commodity fetishism, Marx described workers as alienated, in that they did not have a living relation to the product of their work. Today, this alienation, which is inseparable from the accumulation of capital, extends to the biological and physico-chemical: when a company files a patent to claim ownership of an Amazonian plant, when seeds become products, when natural resources are pure objects of speculation, it is capitalism that is becoming the environment, while the environment is becoming capital.

4. This is the historical context in which speculative realism has emerged. According to this holistic way of thinking, human beings and animals, plants, and objects should all be treated equally. Bruno Latour, for example speaks of a “parliament of things,” and Levi Bryant a “democracy of objects.” With his “object-oriented philosophy,” Graham Harman is trying to bring objects out of the shadow cast by our consciousness, bestowing on them a metaphysical autonomy by placing collisions between things and relations between thinking subjects in the same category, separated only by degrees of complexity. If we consider the world in terms of substance, as the speculative realists invite us to do, we of course cease viewing it as a network of relations. Being takes precedence over knowledge, the thing over the consciousness considering it. A recent essay by Levi Bryant, The Democracy of Objects, attempts to “think an object-for-itself that isn’t an object for the gaze of a subject, representation, or a cultural discourse. . . . The claim that all objects equally exist is the claim that no object can be treated as constructed by another object. . . . In short, no object, such as the subject or culture, is the ground of all others.”(2)

5. It is no coincidence, therefore, if the art world has recently taken up the not unrelated concept of animism. An exhibition with this title, organized by Anselm Franke in Bern, Antwerp, Vienna, Berlin, and New York, invoked Félix Guattari in addressing the subject of animation outside political or post-colonial norms. What does it mean to say an object has a soul? In fact, is this not precisely the essence of a colonial process? To pin human properties on an object, or attribute speech to an animal—these are things that argue in favor of an extension of the human domain. Contemporary art is constantly oscillating between reification (the transformation of the living into a thing) and prosopopoeia (a figure of speech that represents a thing as endowed with a voice). The relation between the living and the inert seems to constitute the main tension in contemporary culture, and artificial intelligence is at the center of it all, like an arbiter. Indeed, ever since Philip K. Dick, science fiction has been constantly exploring the theme of the borders between the human and the machine. But artists today exhibit poetic machines, robotic or vegetal humans, connected plants, animals at work, etc. What we see in these artworks of the early twenty-first century is the circuit of life-forms, but from a political angle: all things and all beings are presented here as convectors of energy, as catalysts or messengers. Animism is unidirectional: it credits inanimate entities with a soul, whereas contemporary art explores life in every direction.

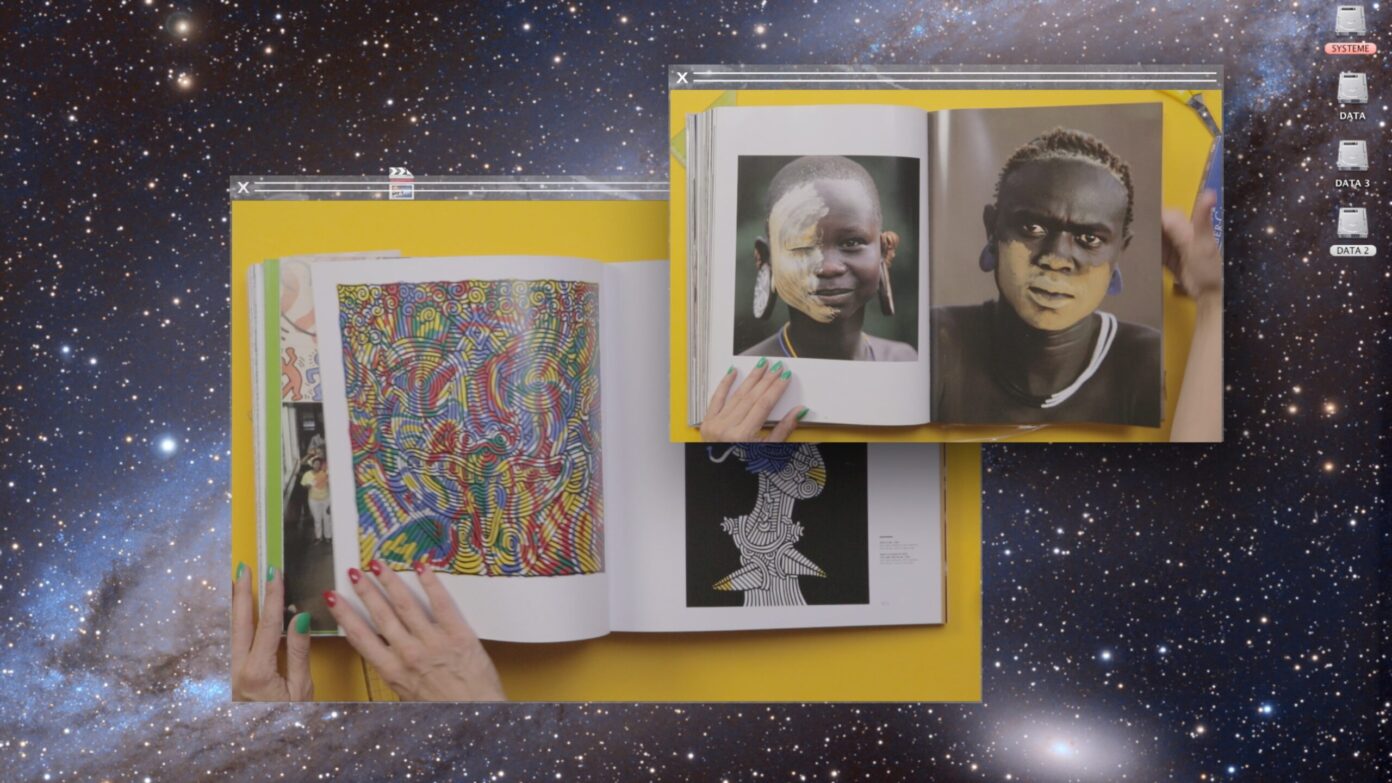

A new generation of artists is exploring the intrinsic properties of materials “informed” by human activity, notably polymers (Roger Hiorns, Marlie Mul, Sterling Ruby, Alisa Baremboym, Neil Beloufa, Pamela Rosenkranz) or critical states of matter (pulverization in Peter Buggenhout, Harold Ancart, or Hiorns). But polymerization has become a principle of composition, the invention of supple and artificial combinations of heterogeneous elements, as evident in the videos of Laure Prouvost, Ian Cheng, Rachel Rose, and Camille Henrot, the installations of Mika Rottenberg, Nathaniel Mellors, and Charles Avery, and the paintings of Roberto Cabot and Tala Madani. Others exploit the effect of weight, transposing the lightness of pixels into monumental objects (David Douard, Beloufa, Matheus Rocha Pitta, etc.).

6. Central to the context in which these “object-oriented” modes of thought are emerging is economic globalization. This has been accompanied by a process of reification which now seems so “natural” that bestowing a soul on objects would be to inoculate them with our own servility and, in a way, to contaminate them with our own alienation. In a world that is capitalist through and through, the living is none other than a moment of the commodity, and the being a moment of the Great Reification. An alienated humanity proves incapable of freeing the world of things: on the contrary, all it can do is contagiously propagate its own alienation. Whereas the whole world has become a potential commodity, to consider it philosophically as a set of objects is to go in the same direction as global capitalism. “There is only one type of beings,” writes Levi Bryant: “objects.”(3) All living things and the whole domain of the inert are thus drawn into the goblin tricks with as their only protagonists, back in Marx’s day, the workers and their products.

Anthropocentric activities

7. Today, in the name of the critique of anthropocentrism, the subject is under attack from all sides. More generally, we may note that ever since post-structuralism ran out of steam, the invisible motor of contemporary thought has been the systematic critique of the notion of the “center.” Ethnocentrism, phallocentrism, or anthropocentrism—the proliferation of these highly derogatory terms indicates that the a priori rejection of any kind of centrality constitutes the great battle of our times. Deconstruction can exist only in the approach to a centrality, of whatever kind. The center, as a figure, represents the absolute bête noire of contemporary thought. But then isn’t the human subject itself the supreme center? It was therefore bound to be caught up in this general suspicion whereby today’s thought metes out justice on any kind of pretension. The true crime of humanity, after all, lies in its colonial essence: since the dawn of time, human populations have invaded and occupied those on the fringes, reducing other forms of life to slavery, exploiting their environment to an absurd extent. But, instead of trying to redefine relations between their fellow creatures and other beings, rather than helping to formulate other kinds of relations between the human and the world, contemporary thinkers have merely ended up reducing philosophy to a constantly ruminating bad conscience, to a simple act of contrition, and sometimes even a fetishism of the peripheral. Is not this spectacle of humility, which we call contrition, an extension and reversal of the old Western humanism?

8. Since the 1990s, art has highlighted the relational sphere and taken inter-human relations as its main sphere of reference, whether individual or societal, convivial or antagonistic. Judging by the immediate success of speculative realism in art, however, it would seem that the aesthetic atmosphere has changed. In fact, the criticism leveled at relational art is that it is too anthropocentric, or even too humanist. Envisaging the human as an aesthetic and political horizon, or even extending its domain to those of the object, networks, nature, and machines—to some, these things appear intolerable or outdated.

There is a degree of bad faith here, for art generally consists in advocacy for the human. And the major political challenge of the twenty-first century is, precisely, to reintroduce the human wherever it is in abeyance. In computerizedfinance, in markets given over to mechanical regulation, but above all in policies whose sole criterion is profit.

9. By extension, what would an exhibition be like if emptied of all “correlationism”? This term is used by Quentin Meillassoux to indicate that all knowledge of the world is always the result of a correlation between a subject and an object, a view typical of Western philosophy. The hypothesis is fascinating, but leads only to an impossibility. The notion of art itself would disintegrate here, for it is founded, precisely, on and within correlationism. As Duchamp said, it is the beholder who makes the picture: no sooner is it withdrawn from the gaze than it goes back to being an object. The difference lies in what an activity generates: collisions between objects, data that can be analyzed by an intelligence, or what artworks produce, that is to say, unpredictable and fertile Brownian motion.

10. Quentin Meillassoux raises a fundamental question: how do we grasp the meaning of an utterance that bears on data existing before any kind of human relation to the world, before the existence of any kind of subject/object relation? In a word, how do we think about what exists totally outside human thought? He goes on to develop the concept of the “arche-fossil,” designating a reality that existed before the presence of any kind of observer.(4) Human consciousness is, in effect, a universal measure, in which regard it can be compared to money, which Marx defined as the “abstract general equivalent” in use in the economy. By raising the theoretical question of the “arche-fossil,” Meillassoux positions philosophy in a relation to the absolute, which here is envisaged in the form of pure contingency. Now, art is only the “currency of the absolute,” to borrow André Malraux’s remarkable expression: that is to say, what remains from human commerce with what is outside it, the surplus from humanity’s relation to the world.

11. Art is also the place where the human and the non-human are entangled, a presentation of coactivity as such: multiple energies are at work there, logics of organic growth work side by side with machines; the set of relations between regimes of the living or inert remain active there, in tension. Contemporary art is a point of transition between the human and the non-human, where the binary opposition between subject and object dissolves into multiple figures: from the reified to the speaking, from the animated to the petrified, from the illusion of life to that of inertia, the maps of the biological are constantly being redrawn.

“The Great Acceleration” is presented as a paean to this coactivity, to the embraced parallel between the different kingdoms and the negotiations between them. The exhibition is organized around the cohabitation of human consciousness and animal profusion, the processing of data, rapid plant growth, and the slow movements of matter. We thus find prehistory (the world before human consciousness) and its mineral landscapes alongside vegetal grafts or couplings between humans, machines, and animals. Reality is at the center: the human being is simply one element among others in an extensive network, which is why we need to rethink our relational universe by including new interlocutors.

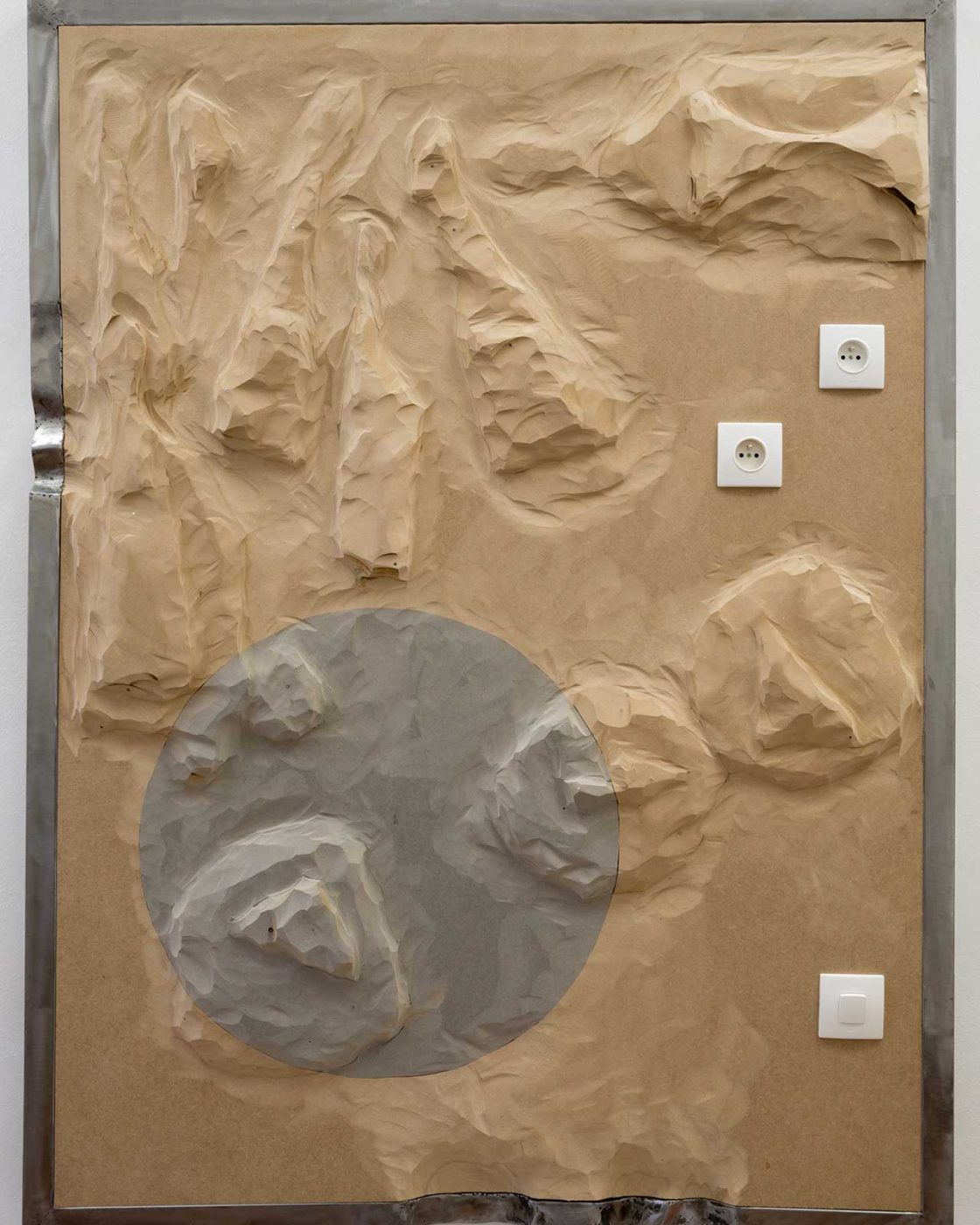

12. In this space of coactivity, the term form takes on new meanings. How do we define it so as to go beyond Roger Caillois’ famous classification, which distinguished between forms born from growth, by accident, out of will, or by molding? How do we define the subset within which, in an exhibition, these different regimes interact? What I call exforme is the arena of a struggle between a center and a periphery, form as something caught up in a process of exclusion or inclusion, that is to say, any sign in transit between dissidence and power, the excluded and the admitted, object and discard, nature and culture. From Courbet’s Stonebreakers to the pop aesthetic, via the subjects of Manet and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, the history of art is rich in exformes. Over these last two centuries the links between aesthetics and politics come down to a series of movements of inclusion and exclusion: on one side, a constantly reiterated sharing between the signifying and the unsignifying in art, and, on the other, the ideological frontiers traced by biopolitics, the government of human bodies. The ontology proposed by speculative realism brings with it new examples of exformes, and that is its main impact on contemporary art.

13. The engine of economic globalization is the ideology of “growth,” in other words, the narrative of an exponential development that is purportedly crucial to the future of humanity. For Jean-François Lyotard, “Development is not attached to an Idea, like that of the emancipation of reason and of human freedoms. It is reproduced by accelerating and extending itself according to its internal dynamic alone.”(5) “The Great Acceleration” is also this process of the naturalization of capitalism: having become organic and universal, it is the natural law of the Anthropocene; its major tool is the algorithm, on which the world economy is now founded. For Lyotard, the only known limit of industrial “development” is given by the life expectancy of the sun, “the only challenge objectively posed to development.” In a world governed by the ideology of infinite growth, what might be the place of individual emancipation, which has been the horizon of culture since the Enlightenment?

14. The foremost ambition of speculative realism is to blur the border between nature and culture. The former, it would seem, is governed by mechanical causality, while the second is the domain of meaning, of freewill, of representation, of language, etc. But wasn’t this subject/object dichotomy which, according to its proponents, governs Western thought, overturned in earlier periods? In his famous text from 1969, “What Is an Author?”, Michel Foucault unhitched the discursive field from the notion of the subject, using the alternative notion of “fields of subjectivation,” defined as a combination of heterogeneous elements. Structure already constituted an alternative to the humanist subject: “the text is a historical object, like a tree trunk,” said Foucault. But isn’t the most surprising postulate of speculative realism the eradication of the concept of structure, the disappearance of which creates a short circuit creating direct contact between human beings and the world of things? However, it is surely difficult to address economics or politics if we cannot envisage them as structures.

15. In the “flat ontology” claimed by speculative realism, which places all the objects that make up the world on the same level, art is bound to enjoy exceptional status, because it exists only in the dimension of the encounter. Its mathematical essence is the figure Omega, which means the infinity of primes +1. It is this “+1” which defines art, that is to say, when a unique encounter, virtual or otherwise, transforms an object (speech, action, sound, drawing, etc.) into a work that revives this infinite conversation we call “art.” Art could then be viewed as the cardinal place of the signifying (everything here makes sense), since meaning is the precondition of art’s existence. In this space, objects are essentially transitional. In art, nothing remains reified for long.

(This article was published in Stream 03 in 2014.)