Artificial worlds

As a philosopher, do you feel that we are living in a time of rupture or revolution? If so, then what do you see as its major characteristics ?

In certain respects, we are always living in a time of rupture. We have to be clear about the terms we use and clearly define what we mean by “rupture” and “revolution.” What we can be sure of, however, is that beyond the obvious phenomena such as globalization, aging in the Global North, and urbanization, the major event in the Western world is the accumulation of technical innovations. Three successive industrial revolutions have left their mark: that of 1800, with the engine and the railway network; that of 1900, with electricity, gasoline, and automobiles; and that of the present day, with the onset of information technology and its encounter with the world of telecommunications, which together I call tele-computerization.

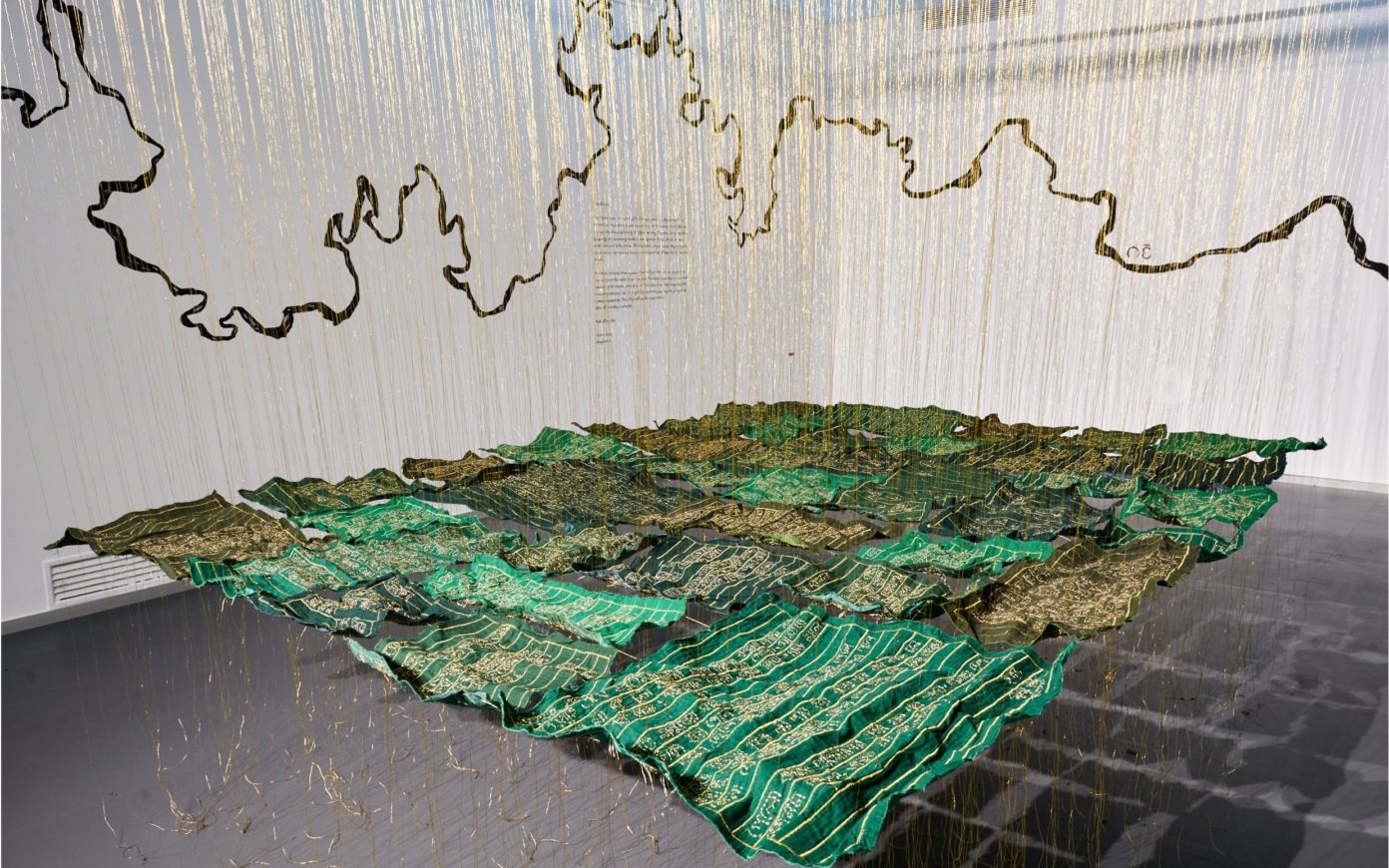

Not only are these technical innovations accumulating, but they are also accelerating. Everything is happening very fast and we must think at the same time as we create these artifacts—a challenge that we have never faced in our history. We are continually creating technical innovations that we don’t have time to understand or assimilate. One thing comes after another, and moreover, international economic competition (especially between large companies) happens at the speed of technological innovation. From a more philosophical point of view, to quote Georges Balandier, we are constructing new New Worlds, artificial worlds.

Cultural and anthropological transformation is the order of the day. But rather than a rupture, let’s think of it as a generalized form of accelerated technologization of society, individuals, cities, and places. A transformation of technology that leads to the augmented human, the connected city, and perhaps in the future, the Internet of objects and nano-biotechnologies.

The techno-scientific economy is an extremely powerful new reference point. The distinction between research and applied science has almost completely disappeared. Yet, paradoxically, this economy is coupled with a symbolic shortcoming, because we have lost the founding myth of progress along the way.

Scientists still believe in scientific progress and technicians still believe in technical progress, except that this grand narrative is shattering and caving in. The power of technology has thus lost its role as a provider of meaning. Quite the contrary—it systematically creates not well-being but a sense of unease, as well as cultural, social, and economic inequality. A gap exists between the power of technology (which was generated in the Western world as a function of an essentially Christian view of the world, before being revisited by Descartes, Bacon, and Marx, and then transferred into the secular god of techno-science) and a certain type of dismay, because we have both conquered power and lost sight of meaning.

Our history is inextricably linked to techno-science, which involved the domination of nature in addition to the spirit of conquest. It began in 1492, with America. Conquering the external and not simply nature—anything weaker, outside of us—is a centerpiece in the history of Western Christianity. It was not, as Max Weber would have it, simply a case of Calvinist sects (an interesting phenomenon, but one which remains relatively secondary). We have always looked at other populations in a Western and dominating way. Today, globalization has put a mirror up to the West that poses the question, “What is my vision of the world? Does it still hold firm?” This is due to its own internal crisis, the collapse of its myths, and its confrontation with civilizations that do not share the same vision of the world. It forms part of the identity crisis in the Western world and an interesting potentiality of globalization, in a cultural sense, above and beyond the economic-industrial competition that often takes the limelight. Our world is full of uncertainty; our symbolic references have crumbled in the face of powerful worldviews that are not the product of the domination of nature, or scientific and technical forms of rationality.

Another important component of this shift, this upheaval at the heart of the philosophy of progress itself, is that when it was being theorized, particularly by Condorcet at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it opened up two paths: one of capitalism, which was to be pursued by way of the economy of techno-science, and one of socialist utopias, on which I have done quite a bit of work—Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, and many others. These two different worldviews structured the two previous centuries, between the French revolution in 1789 and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Yet they have given way to the dogma of efficiency. Social and political utopias have been absorbed by technological utopias.

At the most, what we’re living is the triumph of science fiction, of Jules Verne, of Hollywood blockbuster films—that is to say a vision of the world in which otherness (the symbolic is otherness, the great Other, God, etc.) is no longer a dividing point for the world as it was for at least a century, roughly speaking between the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Berlin Wall, when it reached its climax during the Cold War.

Today, otherness is technology—it’s the robot, the technologically-infused living forms, the human-machine. The alter ego is within us in this new form of otherness—it is scientific and technical production. That’s what accounts for its symbolic weakness. We’ve taken what little symbolism remains of the celestial, spiritual, and ideological realms and transferred it to technical objects. This fall is broken into three strata—strata, because I’ve never learned history in terms of linearity, but in terms of geological layers—on the surface is 1989, and then another sedimentary layer just below which was a longer period, that of the secularized techno-scientific vision of the world, and finally, another deeper stratum, roughly one thousand years ago in the case of the Western world, which was the shift from religious otherness to techno-scientific otherness. One advantage of thinking in terms of historical strata is being able to see that those things that are buried can surface again, not unlike the lava in a volcano.

That is what we have partly forgotten, because that’s how technology works: newer technology replaces the old. Innovation is rather intensive, for example with the iPad, smartphones, and connected cars. Yet old forms of technology are coming back, right inside of technological development itself. All too often, we have a present bias and think in terms of tabula rasa, of ruptures.

Meaning works deep within. For example, the Saint-Simonean schism thinks of the industrial revolution in reference to the Gregorian schism of 1075, when Pope Gregory distinguished temporal power from spiritual power. On one side, there is the spiritual, the symbolic; and on the other, the temporal power that we’ve brought together in techno-science, primarily from the seventeenth century onwards with Galileo, Bacon, Descartes, etc. These debates have gone on quietly for a thousand years and we tend to forget that. Not everything started with the Internet, or in the 1980s, even if there was indeed an intense acceleration of technical innovation over the course of that decade. Nothing can be understood without referring to history. Memory and forgetting must be combined.