Implementing Public Space

- Publish On 3 January 2017

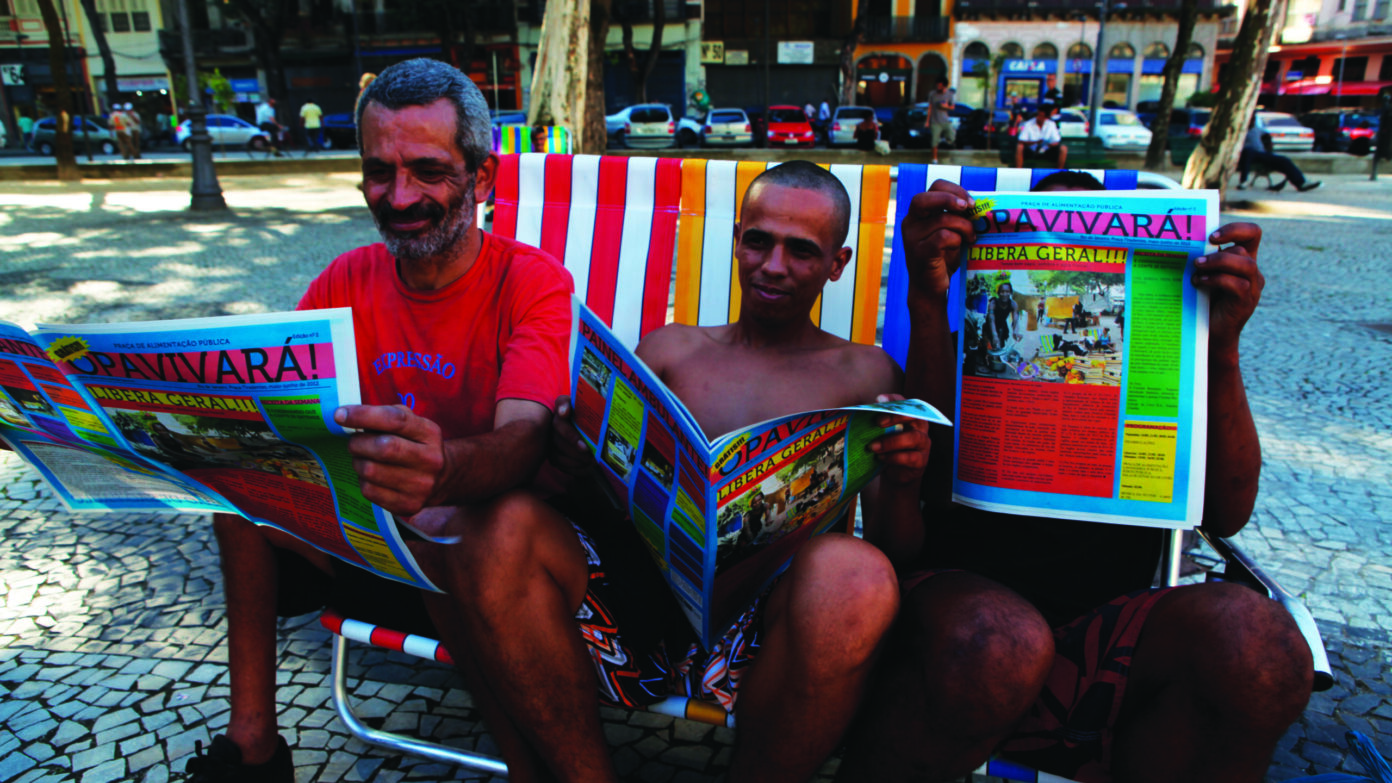

- OPAVIVARÁ !

- 9 minutes

Re-emerging in the context of Brazil’s economic boom, Rio is fascinating for contemporary urban thought and possible models of the city of tomorrow, due to the ubiquity of nature in its urban fabric, the often informal dimension of its urban development, and its lively public space. Artists are the most apt at rendering this lively carioca “spirit”. In this case, the members of the Opavivará collective exhibit their performance work within public space, thereby questioning the absence of an urban project, the notion of collaboration, the balance of power, social imbalances and the issue of mobility in Rio.

OPAVIVARÁ! is a collective of Brazilian artists who conceives performances in the public space to question the absence of an urban project, the notion of collaboration or the relations of power in Rio de Janeiro.

Roberto Cabot is a painter, sculptor and musician.

Roberto Cabot : I feel that you create more places than actions in your works. How would you define this idea of “place” in your work?

Opavivará : More than places, it is a question of “situ-action”Situ-ação in the original Brazilian Portuguese.—the place is given by an action in space. We create an envelope which receives an action—a space designed for the intimate relationships which are instigated there, a membrane between the public space and the intimate space. It is a social experiment. The place is thus based more on the relationship between things and people than on its architecture or its vegetation. In our interventions, the space is kept as open as possible to what can happen or not happen. For a space to be genuinely public, it must keep this openness.

Rephrase public space

There are different strata in our work: we choose a public space in the city and insert a device that is either quite minimal or very complex, but which doesn’t replace the people circulating in the place. Sometimes, the device is even camouflaged in the urban fabric and is only brought to life on contact with people. The public is an integral part of the work. For instance, Cozinha Coletiva was described as: “table, gas cooker, chairs, dishes, food, and people.” Individuals are the very bricks and mortar of the architecture of our works. In a way, that runs in direct contrast with modern thought and its very concrete vision of urban planning where the city is a stack of architectural elements, of concrete, etc. Our architecture is based on living cement.

Roberto Cabot: Regarding this issue of public space, there is a phenomenon I find very interesting at this moment in Brazil: rolêzinho2, because it questions the border between public and private space. A mall is something private in legal terms, but at the very same time, access to it is open. As a result, aren’t these inter-relationships between people and things what decide whether something is public or not?

Opavivará: There is also the issue of the use of public places which have often been designed for a specific purpose—whether it has been achieved or not—and which transform over time. But yes, our work explores this issue, the way in which participants take control over the work and appropriate public space. People start saying to themselves “Ja é nosso” (This is ours) and the private becomes public.

Our works do not only reaffirm the public sense of public space but also create a tension in the relationship between the public spaces and private spaces which form the city. When we set up a kitchen on a public square—a device which is usually found in a private space, governed by its own strict laws—this domestic situation clashes with that of the plaza. That leads to a long series of questions: what is it which makes a public space public? What kind of relationships develop in a kitchen? On a public square? What if we mix both environments? What is certain is that it breaks the parameters which govern the public space: the domestic domain and the public domain are immediately swapped around.

The urban environment—which is regulated by the laws of labor, of commerce, etc.—is contaminated by the most subjective laws of the kitchen, which are specific to each family. As soon as you set up a kitchen, the city square becomes more subjective, relationships which are more affective and less commercial emerge, and it becomes a social experiment. Our work blurs the rules and actually people start out not knowing how to behave, not knowing what they can or cannot do. That is the transformation of space we put forward, because people don’t know how to use public squares and gardens anymore—the public space doesn’t belong to anyone anymore.

Roberto Cabot: You work in Rio de Janeiro, a very special city where there is considerable confusion between public and private spaces. Does that idiosyncrasy influence your work?

Opavivará: Yes, there is this confusion which forms part of Rio’s identity, but we also work in private and institutional spaces which have their own rules that we put under tension. We are constantly playing on what can or cannot happen in a given place. For instance, the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo invited us for an event combining art and cuisine; they expected to see chefs whereas we wanted to have a kitchen which was open to the public—something they were very concerned about, for health reasons among others. We had to negotiate toe-to-toe with them because their institutional vision went against our understanding of a work of art that interacts with the public.

Part of the concern of our work lies in this reformulation of the spaces where we intervene. The objective is to disrupt the rules governing a given space, to create tensions and membranes enabling other connections. When we intervene in a public space or an institutional place, there is always a regulatory bureaucratic framework which we have to deal with—it’s very much part of our work. There is a form of negotiation where we are told: “Hey, artists! You can do this, but you can’t do that.” We reply that it doesn’t make any sense if we don’t do this, but, OK, we can drop that.

To come back to the rolêzinho phenomenon, it is really interesting because fundamentally the arbitration between public and private spheres is linked to what you want to see in a place. Malls have always wanted to attract as many people as possible, to have people consume things, but suddenly there is the rise of the lower middle-class, which now has some purchasing power, but that creates an issue because they “invade” the place with an unexpected behavior and because they have a different skin tone and another culture. Discriminatory reflexes are never far away. I remember a meeting at the subprefecture, when we had this kitchen on the plaza, they said: “That isn’t cool, you’re attracting hobos to the plaza.” And the City Hall had the same attitude: they hadn’t understood all the facets of this artistic project; they took us for a soup kitchen.

Roberto Cabot: That is the main difficulty with the system. That being said, your relationship with the municipal authorities is very peculiar—they often say that in a way you represent Rio, that you are their darlings, and at the same time you irritate them.

Opavivará: We certainly aren’t the darlings of the City Hall. As a matter of fact, we nearly don’t have anything to do with them. Although, maybe we are cherished by them in a way. (Laughter) After all, if we don’t encounter so many problems, it must be that in some way they need us.

Suggest an experiment

Roberto Cabot: Exactly. You are dodging the issue a bit but I can understand that. Furthermore, it is very amusing to see that they keep pushing you to do things despite the fact that you are making their life more difficult. In your way of transforming spaces, there is something else which is very carioca: transience.3 Is that a strategy within your work?

Opavivará: Opavivará is doing some historic work—not historic in the sense that we are inscribing it in the history of art but rather because our works have a very strong historic component. This issue of transience also comes from the fact that we propose a sort of ritual, an experience which differs from the continuous flow of daily life. People do the same thing everyday and then there is an event, a day of the year where the tribe gathers, does something exceptional which becomes a kind of ritual and we work on that. There lies the meaning of our urban interventions: we suddenly take control of a space, transform it for a short time and make a ritual out of it. Just like with the kitchen on the public square: people start doing things they don’t usually do, understanding the urban space and the world in another way, understanding themselves through the lens of this transformation. That creates a historic moment because it distances itself from repetitive daily routine. Transience is something fundamental in our approach: we aren’t trying to build a large imposing monument and make it last forever.

Roberto Cabot: In a way, transience represents genuine duration. Classical three-thousand-year-old buildings have crumbled and humanity continues to exist. I feel this organic approach will last longer than marble.

Opavivará: Probably. One of our works is very much within that spirit: Eu amo o camelô4. It was an immediate reaction to the new beach regulations, which ban just about everything, including hawking. Overnight, the camelô became a delinquent and became poorly considered, and we wanted to put that in tension. Why wouldn’t the image and spirit of the city take form in this transient figure, in this camelô, this guy who goes back and forth but has been in the city forever. The Morro do Castelo (Castle Hill) has fallen but the camelôs are still there. Our culture is fundamentally transient and ambulant. The importance of this campaign was to highlight this figure of the transient city, to shift public perception so that people, including in the City Hall, realize that the ambulant mate hawker forms part of Rio’s intangible heritage.

Roberto Cabot: Yes, it is a fundamental characteristic of Rio: everything is ephemeral and transient. Nothing is built with the idea of duration; it is always assumed that things will crumble, disappear, be transformed—there is no culture of maintenance.

Opavivará: Still under construction, already in ruins. This is something very important in the way we conceive the occupation of public spaces: the aim isn’t to create monuments aiming for eternity but things which can be camouflaged and contaminate the urban fabric. The camouflage is ephemeral because the city changes and our way of occupying it adapts to this change. What is interesting right now in Brazil is that the multitude, or rather certain social classes, are starting to have more say, to engage in dialogue with the state. This year’s demonstrations have carried much more weight in decision-making because the state now must take into account the importance of social networks and the media.

Roberto Cabot: This is a fundamental issue. In our segregationist society, nobody was expecting that suburbia would demonstrate in Leblon,5 but that happens because all of a sudden there is some mobility available, a structure to come in from the periphery, people can pay for tickets, they have a GPS in their phone and the Internet to gather, to get organized. I take this opportunity to address the issue of mobility because you have created a sensational work on the subject: the Transporte Coletivo. I would like you to talk a bit about that work, while recalling that Rio de Janeiro is one of the world’s most complicated cities in terms of mobility because you have the sea, mountains, a tunnel. It is a very complex topography and the history of the city is one of a struggle for expansion in every nook and corner, with these gigantic monsters in the middle of our landscape.

Opavivará: It is a work which was conceived as a proposition of public transport and which must really be experienced to be understood. In that way, you perceive the city in a different fashion—you don’t have a protective glass panel and you have more time. This work puts into tension the idea of mobility itself as well as the public space because it is also an open and free form of transport which goes in places buses cannot reach. We put a great deal of thought in creating a ride which would make it possible to see the city with fresh eyes, especially the city center, with the idea of considering it as a whole. We created several transit loops starting from the Tiradentes Square. We also wanted to see how people would organize with a driver at the front as well as different intermediary drivers. There is an aspect of this work that people didn’t understand because they were convinced that we had built these tricycles when in fact they already existed—they can be borrowed on weekends on the Aterro do Flamengo6 to cycle around and have fun. It is therefore also a transient work in the sense that it is a ready-made, a shift in an existing structure with a purely recreational application to another context where it becomes a tool for the observation of the city. It also creates a clash with the city—we wage a war against buses but with fairly strange weapons. In the end, we are taking hold of a recreational tool, placing it in an urban context in a fairly playful manner and when we place it right in the middle of the road, bus drivers step down from their buses to come and cycle with us.

Another important thing, linked to the specific topography of the city, is that it enables us to imagine more hybrid transport systems. You cannot move around the morro or favelas in the same way as on the asphalt. The interconnection of different forms of hybrid transport adapted to each environment would make the city much more fluid. We wanted to show just that: that it is possible to have a strong public, collective transport which is completely different from what exists.

The idea of trying to slow down the production process is also present in our work. From the standpoint of urban planning, mobility is only conceived in a functional way, for people to go to work. Going from home to work, from work to home—always with this logic of production. On the other hand, our poetics also deals with the other side: pleasure, because people nowadays are afraid of pleasure. In the case of Rio de Janeiro, there is also a nearly historical dimension to this because the means of transport which bring the masses to work have always been instruments of daily torture: Rio’s buses and trains are really horrendous. So instead of simply switching production and leisure, the objective was also to replace suffering with pleasure. This is a work which is emblematic of our approach, our methodology, because it is a means of transport with collaborative propulsion. It asks a collective question; it is a means of transport where you aren’t a passive passenger waiting for the driver to perform his job well—you are there together.

Bring together all social classes

Roberto Cabot: What are the relationships between the types of actions you are doing and these spontaneous things which are happening in the population—do you think it is in the spirit of the times, that things are happening by themselves? Is this a phenomenon you notice and that you integrate into your work, or is it a much more risky relationship?

Opavivará: We think a lot about that dimension. For instance, for the installation of the kitchen on Tiradentes Square, the work was called Opavivará Ao Vivo (Opavivarà Live), but the kitchen itself was called Praça de Alimentação Pública (Public Food Plaza), in direct reference to the mall’s food plaza: an ironic name for a space where people will meet and share among themselves. But there are a lot of things in our actions which are purely coincidental, for instance our work on the camelô. The fundamental underpinning of our work is communicating with the population, because we only intervene in the public space and we want to reach as wide and diverse an audience as possible. We seek a language of camouflage to blend with the language of the city. It would be meaningless to show up with a fully completed project in this place which is a delirium, a mix of languages. Opavivará looks like a variety theatre: we appropriate the major news topics or things we catch in mid-air and then suddenly make headlines with them.

Roberto Cabot: Most of today’s conflicts, these spontaneous movements of society, are nearly always linked to issues of public space and mobility. But strangely there are very few specific demands on the subject. In my opinion, the central issue is the right to make use of the city—we now have an entire population who wants to enjoy its city.

Opavivará: Bearing in mind that enjoying means being able to consume. What’s the use in coming and going? Consuming. Mobility itself is a consumer item. For that matter, there is a major automobile boom in Brazil, with the lower middle-class starting to purchase cars.

Roberto Cabot: There has been segregation in mobility in Brazil with expensive, comfortable buses with air-conditioning on the one hand, and cheap, old things for the masses on the other hand.

Opavivará: This price difference was true until last year, but since the protests prices have been controlled. There is a lot of discussion about consumption but we have to take care because one quickly falls into an anti-consumerist Marxist rhetoric while Opavivará has always perceived trade as a moment of exchange, of interconnection. If we understand the city as a place for relationships, we must work with trade, with the market.

Roberto Cabot: To conclude, I want to talk about an emblematic space for Rio which you think about a lot: the beachfront. It is a very strange space because it is public and, once more, we had problems: with the arrival of the metro, of mobility, suddenly the elite found itself invaded on its beaches. Given that constitutionally, the beachfront is a public domain administrated by the Navy—that is to say, it belongs to everyone. But then suddenly, there is this problem: the “invasion.”

Opavivará: Our beachfront has never been calm, it has always been very noisy. And there has always been a bit of diversity due to the favelas embedded within the posh districts, but it was different because the inhabitants of these favelas worked for the rich.

Roberto Cabot: Yes, in the end, this serving “middle-class” had adopted the habits of the rich—a way of behaving, not being too noisy, not touching people, etc. They had assimilated the restrictions of that education. Everything has changed with the arrival of the suburbans: people with very different bodies, educations, and behaviors; it was disturbing. The elite still had retained old-fashioned attitudes. That is why it is interesting to work on bodies and their appropriation of space as you are doing.

Opavivará: Yes, an aspect of our work is dedicated to fostering these relationships, building an impossible and unhoped for context where all the social classes within the city meet in the public space and also fight against bias and fears. I think the beach is a perfect urban model. In Rio, the entire city is on the beachfront: there is the mall, several clubs. It is like an extension of people’s homes because they are there in the public space yet stay in their own intimacy, naked, lying down. It is an open space, with this geographic condition: the city stops here, it goes no further.

Roberto Cabot: Even the clothing is different: the dress style changes from the moment you set foot on the sand. On the sidewalk, everyone is dressing up, cleaning their feet to put their shoes on; on the sand, bare feet reign supreme, you stay naked and everything goes well. But if you walk around naked in the city center. That’s something very interesting: the setting isn’t the only thing which counts but also what happens in people’s heads. When a guy arrives at the beach, he transforms himself.

Opavivará: What is interesting is also the pattern of occupancy: when the beach is full and you are looking for the best spot. It is a completely organic occupation because the City Hall could also mark off a dedicated accessway to the sea, parcel out the beach, etc. Maybe it will become like that because, day after day, they are giving in a little more to the market. I find it incredible to see how the beach, despite all its invisible membranes, its social clubs, its locations, is a gathering place. You have the space for families, the space for gays, the space for the lower working-class, the clubs—if you want to cross any space, you just need to walk through.

But I think our beachfront has a characteristic: it isn’t calm. Many people come from a long way, they get there and don’t find quiet because there are hawkers, altinho players.7 The beach is full of activities. It is imbued with Rio’s life. The beach is really a unique and marvelous place and ultimately it becomes strange when it is too calm.

Roberto Cabot: I think the beach also determines what Rio is in the sense that, to come back to economics, the entire logic of real estate prices is under its influence.

Opavivará: But that is also ephemeral and transient: the city hasn’t always been like that. São Cristóvão was the poshest district during the Empire, and then Catete and Grajaú became more trendy.

Roberto Cabot: And there they discovered the beach.

This article was published in Stream 03 in 2014.