In Search of Nature-Based Solutions

- Publish On 7 October 2021

- Frédéric Ségur

Increasing the place of plants in cities plays a key role in mitigating the urban heat island effect, but trees must be addressed as a systemic issue, interfacing with the air, the ground, and water. For Frédéric Ségur, we must re-engage with the knowledge of urban forestry in order to regain our intelligence of trees and counter the mistaken assumptions on their life expectancy in urban settings. Beyond political declarations, the idea is to plant well rather than simply a lot, and to provide adequate conditions for them to develop—including space and living soil—and to take into account the ecotypes, but also to get the plant palette to change in relation to climate change.

You work as an “urban forester” for the Greater Lyon Metropolis and head its Plan Canopée, a project that brings together a plurality of urban stakeholders. Could you tell us more about this occupation, which isn’t very well known in France, as well as about what you are doing in Lyon?

When I started my studies, the discipline of “urban forestry,” which had been developed some fifty years ago in North America, didn’t exist in France. All the vegetation in an urban territory must be considered together as a scattered forest, and a comprehensive and cross- disciplinary vision must be adopted to manage it properly. Models, techniques, and principles from forestry sciences are applied, including pedology, phytosociology, botanics, and sylviculture… But given that we are operating in urban territories that are populated by humans, it is becoming critical to complete this forestry-first approach through the inclusion of the dimensions of landscape, architecture, urban planning, and geography, as well as sociology, anthropology, and psychology. “Urban forestry” is this disciplinary mix that has unfortunately always had trouble developing in France. That is why I did part of my training abroad, in Canada, in the UK, and in Australia, before returning to France with the intention of developing this approach centered on the urban tree. That is how I started collaborating with the Lyon metropolis at the turn of the 1990s, at a time when the question of nature in the city wasn’t a priority given that the Trente Glorieuses post-war economic boom was just ending and that the functional and utilitarian vision of the city was still very present. Since then, I’ve been working on elaborating strategies to introduce issues relating to nature and the landscape in the culture of urban planning of the metropolis. I develop projects that try to go beyond the institutional logic and edge towards a territorial one. Plants, water, and soils become tools to devise “nature-based solutions” and increase urban resilience to climate change.

The Lyon Metropolis is currently implementing a project called Plan Canopée, which builds on the Charte de l’arbre [Charter for Trees], the first version of which was drawn up in the 1990s. At that time, the completion of the Cité Internationale neighborhood designed by the landscape designer Michel Corajoud revealed a new way of building the city to the public. There was considerable stir among the population, generating strong social demand for projects giving a new place to the landscape and urban nature. But the change in the municipal team almost halted the momentum. That was

when we started working on drafting a document that, with political buy-in, would establish a firm grounding for the urban landscape policy of the metropolis in the long run. Our second objective was to create a dialogue between strategy, design, implementation, and management, involving a great number of stakeholders with sometimes competing interests. The focus was on creating a tool for dialogue and consensus-building with private contractors we’d be called to work with. The Charter for Trees was born. Passed unanimously, it enabled us to build a metropolitan thought defining shared objectives, that wouldn’t be reconsidered at the end of each political term. The charter laid down guiding principles of diversity, sustainability, and economy that map out the outlines of a long- term philosophy. The idea wasn’t to impose constraints that would bring about a stranglehold on creativity but rather, to define a direction we should be taking collectively, though leaving everyone free to chart their own course.

This charter faces three major limitations however. First, it focused on topiary trees, which had historically fallen under the purview of the metropolis, and therefore didn’t account for landscape issues at the metropolitan scale, nor natural spaces, or a whole range of diverse environments. Second, the charter wasn’t sufficiently well known or shared by key players in the territory. Finally, new objectives that hadn’t been identified during the drafting of the charter had cropped up. The initial drafting in the 1990s was primarily driven by social demand, but issues such as biodiversity loss and the effects of climate change gradually took center stage. This led us to draft a second version in 2011, in order to take a new territorial approach, updated, better shared, and more comprehensive. There are now more than one hundred and twenty signatories, including municipalities, developers, social landlords, trade federations, construction companies, engineering consultancies, business incubators, and neighborhood councils… All these stakeholders form a network sharing a philosophy, ambitions, and experiences.

In order to go beyond the mere ethical and philosophical dimension however, the Charter for Trees had to be augmented with an operational application, which led to Plan Canopée, which strives to take practical action to adapt the city to climate change, in particular by fighting against urban heat islands. The biggest vulnerability of the Lyon territory is indeed its exposure to heatwaves, which have increasingly severe health consequences. From the tree, we have extended our intervention perspectives to rewilding and shading, with a view to increase urban heat resilience.

How does this objective of expanding the shaded canopy cover at the metropolitan scale involve a systemic approach?

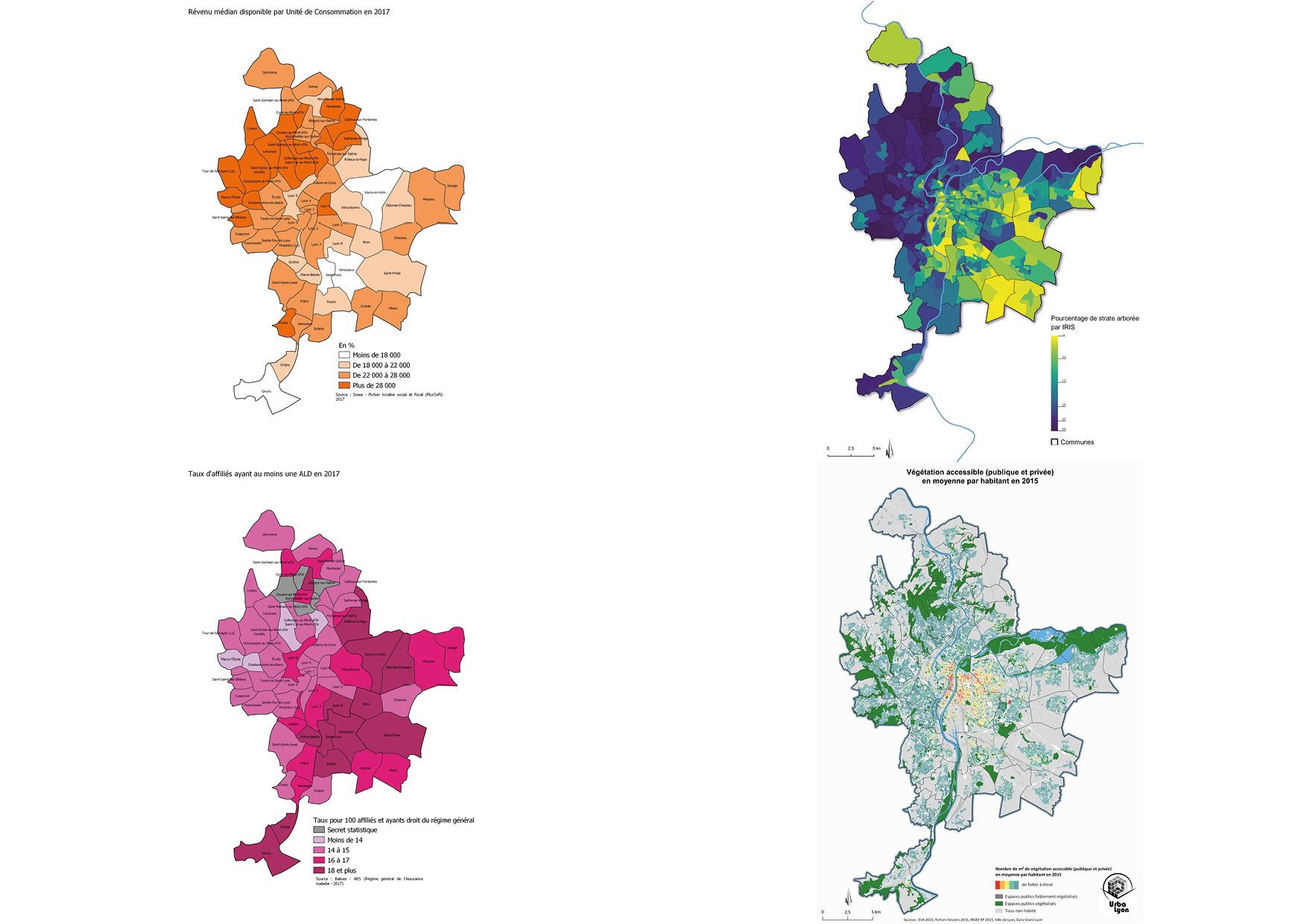

Plan Canopée seeks to engage all public and private stakeholders around a shared, comprehensive effort to rewild the city and adapt it to climate change. This involves planting new trees, but also preserving and tending to the existing tree heritage, protecting and recreating soils, proper water management… Everything is connected, trees aren’t isolated elements. In more technical terms, by cross-tabulating infrared photointerpretation data (which highlights plants coverage) and Lidar imaging (which is capable of measuring the size of objects), it is currently possible to visualize very accurately the distribution of trees within a territory, what is called the “urban forest.” We were thus able to determine that 27% of the metropolis is covered by canopy, which

is very much in line with the average “canopy index” of large North-American cities, a qualitative indicator developed to assess the situation of cities, especially regarding urban heat islands. Urban forestry is very advanced in the United States, and federal services have acquired substantial expertise in that field, which they then apply at municipal level. According to their studies, cities with 30 to 40% of urban tree canopy cover have high levels of heat resilience. The Lyon Metropolis is therefore on the good side of average, though the question is then of course whether there is an upward or a downward trend.

As it turns out, 70% of the canopy of Greater Lyon is located on private property. Only 10% is under direct control of the Lyon Metropolis, 10% under that

of the 59 municipalities, and 10% of other public entities, social landlords, and domains of the state… Moreover, the canopy’s growth potential is also mostly located on private land. Gathering all these stakeholders around the understanding of the need for a comprehensive effort towards rewilding and adapting the territory to climate change was therefore crucial. Canopy analysis has also revealed how unequal its distribution is. The municipalities to the west have an average canopy cover that often exceeds 40%, whereas municipalities to the east have covers below the 27% average, and sometimes even less than 10%. Concurrently, correspondences between canopy surface and other indicators such as heat islands can be noted, but also, more astonishingly, with life expectancy, heart disease, and the exposure to pollutants… Even if these aren’t scientifically established correlations, they are “relational loops.” There is no direct causal relationship but there is a connection between these social and environmental factors. The search for environmental equity, in order to help address this territorial divide that is linked to a wide range of factors related to history, topography, or land use is therefore central to this debate.

In order to increase the canopy surface, the Lyon Metropolis is aiming to have planted at least three hundred thousand trees by 2030 in order to achieve a total canopy surface of 30%. But the number of trees isn’t a good indicator: if you plant ten trees on a supermarket parking lot that don’t develop and die off after ten years, the end result is zero. If you plant a tree under proper conditions and it ends up offering 100 m2 of shaded area after twenty years or so, this is a clear benefit. Developing the canopy thus amounts to improving the quality of the plantations in order to achieve sustainability goals in a context of climate change that impacts the very nature of vegetation. Based on that observation, we have defined a program of roughly thirty actions at the nexus between trees and urbanism, health, economic development, biodiversity, diet, street maintenance, sanitation, water management, land use, and so on. The idea was to introduce a series of financial and technical tools to stimulate and support initiatives at different territorial scales. We are currently developing new processes for civic engagement, as well as partnerships with businesses, following new economic and governance models around sponsorship, in order to speed up the development of the canopy both in the public and private domain.

The distinctive character of this plan lies in the change in attitude of the metropolis. Previously, it would assume the posture of an expert carrying out its own development projects and regulating external projects. It wasn’t instilling a collective and educational dynamic. We wanted to shift from this posture of a “knowing” protagonist to that of a supporter, facilitator, instigator, advisory… in order to enter into a dynamic of ownership by all the territorial stakeholders.

Ecology and the rewilding of cities are now major concerns for urbanites. Does this movement give rise to new urban knowledge and know-how related to tree cultivation?

PWe are paradoxically confronted with a loss of knowledge in certain fields compared with Alphand’s1 times. Alphand had a very interesting holistic vision, informed by the multidisciplinary skills of his team. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the knowledge base in terms of arboriculture developed in the seventeenth, and especially in the nineteenth century, were quite brutally lost with the rupture of the First World War. A major plantation effort had already been carried out, and because nature was at the city’s doorstep, there wasn’t a need to do more. The tree, which had become a key element in urban development strategy receded into the background. Urban forestry competence gradually disappeared due to a lack of training, research, and interest, eventually being redirected only towards natural habitats and forests. The city lost its overall perspective of nature in favor of a vision proceeding more from horticulture, to quantitative greening, and an ornamental approach. This loss of knowledge is clearly discernible. The majority of trees planted in the postwar period are indeed withering, while the trees planted in Alphand’s times, one hundred and fifty years ago, are often still in perfect shape. It is wrong to assume that the city, as an environment, isn’t conducive to the proper development of trees, or that a topiary tree would have a life expectancy limited to thirty years or so: the city is an artificial environment, so the living situation of trees are those we are willing to give them. There is no foregone conclusion.

So why do certain trees die off early while others survive? The answer lies in the soil and its fertility. Alphand’s success comes from the fact that trees were planted in continuous trenches three meters wide and a meter and a half deep, in order to get around the constraint of compacted, polluted urban land that is unfit for plantation. Soil volume and fertility formed the basis of the plantation project. Due to the compartmentalization of knowledge, this comprehensive vision ended up being split among single- purpose service departments focused only on water, street maintenance, plantation… each having developed their own specialities, lingos, and standards, erecting borders rather than thinking of their interconnection. At a time when cars reigned supreme, roads chipped away at the space dedicated to trees, particularly regarding the soil that is supposed to ensure their stability and prevent deformation. When I started working in Lyon in the early 1990s, the standard for planting a tree was 1 m3 of soil, hence the “supermarket parking lot tree” syndrome.

To make up for this lost knowledge, we are trying to return to the quality of the plantations of the nineteenth century by trying to understand the mistakes made in the twentieth century, all the while developing research partnerships drawing on the scientific knowledge accrued during the twenty-first century. The city of the twenty-first century is much more complex than that of the nineteenth century, and it simply isn’t enough to reestablish the technical standards of the past to cure its ills. To overcome this loss of knowledge, we have therefore developed new directions for “nature-based solutions.”

A good illustration of this is the issue of soil use, which truly requires a paradigm shift. The Buttes-Chaumont Park is a prime example: a former gypsum quarry transformed into an urban park during the Second Empire, huge amounts of fertile soil were needed to transform the chalk cliffs into rolling green hills. That soil was imported from the Saint-Denis plain, where urbanization was gradually taking over market gardening plots. Upwards of 200,000 m3 of this high-quality soil was therefore carried away in wagons. Buttes-Chaumont demonstrates the use of a product that arose from a way of conceiving of the city based on urban sprawl. The product is topsoil, and it is produced only through the destruction of natural sites. In order to fashion thirty centimeters of topsoil, which corresponds to ordinary tillage depth on farmland, it took three thousand years of weathering of parent rock and the accumulation of humus by a forest. This process is called “pedogenesis.” When we erect a building, we are simply stripping this living layer and transforming it into a material, into a commodity. When we talk about the soil that is used to revegetate a development, it’s important to remember that it proceeds from the destruction of a natural site that took three thousand years to form and that won’t regenerate alone.

Urban sprawl has long contained the shortage of this material by turning it into one of its by- products. We are now aware of the importance of conserving these fertile lands, but we are facing an unprecedented and paradoxical situation, given that the demand in subsoil increases with the desire to intensify the rewilding of cities. To move beyond this dilemma, the Terres Fertiles 2.0 project [Fertile Land 2.0] was launched under Plan Canopée. We are working to restore a substrate that could perform all the functions of a living soil based on the by- products of urban activity.

Soil excavated during the digging of a car park or a metro can provide a good base material for instance, as the silt and loam content is typically high, helping retain the water needed for the plants in the soil. It is inert from a biological standpoint however, and has low carbon content, which acts as a fuel for soil life. From this earthy base, we are seeking to achieve accelerated pedogenesis. In other words, we aggregate to this mineral matter, organic matter in the form of green waste compost, in order to recover the biological life of the soil. This soil enriched in organic matter is seeded with bacteria, fungi, earthworms, and so on. And it must be left to mature for this aggregation to occur. This allows us to “artificially” produce fertile soil based on the circular economy and no longer by exploiting natural land, which represents a real paradigm shift.

To provide some space for this soil, for years now, we have been working with the street maintenance department on developing techniques to stabilize roadways based on a mix of stones of fairly large sizes, in order to ensure high enough air void to place 45% of uncompacted soil in it. This subgrade layer forms a supporting skeleton that prevents the deformation of the roadway, but also a well- aerated network that enables air to circulate, water and carbon to be stored, as well as roots to develop.

By working on developing nature-based solutions, at the interface between different activities, we elaborate strategies that are adapted to today’s constraints and know- hows. We also advocate a political objective: engaging private stakeholders in innovative demonstrator projects.

Announcing to a contracting authority that is looking to build an ecodistrict that the environmental footprint of the work needed to reconstitute a landscape corresponds to the destruction of several dozens of hectares of natural land is quite effective. Following a co-construction and mixed- governance approach, the metropolis plays a role in mediating, training, setting objectives, and scientific monitoring. The contracting authority and its teams carry out the research and development work, logistics, and so on, while the suppliers carry the economic risk of manufacturing the materials needed to supply the sector. Each player bears a part of the responsibility in this shared, partnership-based approach.

Do new technologies play any role in your urban experimentations or are these primarily based on “natural intelligences?”

We indeed use new technologies in our research and development. There are remote sensors that can collect data on temperature, soil water availability, and tree evaporation. It is then possible to monitor the release of rainwater reserves to supply trees with water during heat waves for instance, which also helps combat the urban heat island effect. It is often stated that the evapotranspiration of a single tree can provide as much cool as five AC units, but this is true only if there is enough water availability. These water supplies are therefore not intended to help trees cope with heat, but, rather, to generate coolness and improve urban comfort. When such water becomes a necessity for the tree’s survival, this becomes problematic, which relates to the issue of the adaptation of planting palettes, which is another topic we’re investigating. The life expectancy of a drip- irrigated tree is equivalent to the service life of the watering system. As soon as the system fails, the specimen dies, often even before the irrigation can even be restored. These new technologies can therefore provide services to humans, but not really to nature itself.

Nature is intrinsically resilient, as long as it is properly understood and we don’t interfere with it. The trees planted one hundred and fifty years ago prove this, though they have never been watered, except perhaps during the first years after planting. In order to protect nature, the solution lies not so much in new technologies as in the understanding of how it operates.

To achieve this, it is crucial to reason in terms of ecology, following a dynamic and adaptable logic. A common current mistake in rewilding is advocating the exclusive use of local tree species. But the local species of today aren’t those of yesterday, nor those of tomorrow, as ecosystems shift around due to climate change. Planting a tree demands looking one century ahead, and we know full well that the environmental conditions that will prevail within cities will be very different by then. This therefore involves choosing a planting palette that is well- adapted to the climate conditions and the urban environment, through the further investigation of what is referred to as ecotypes.

The common oak currently grows anywhere from Italy to Norway for instance. We know that ten thousand years ago, when the climate started warming up after the last Quaternary glaciation, the only place in Europe where oaks were present was in southern Italy and Spain, and they then gradually migrated northwards.

This also suggests that southern oaks, which remained in a Mediterranean climate and on calcareous soils, don’t have the same ecological requirements than those that migrated to Denmark and have adapted to sandy soils, in a much cooler and humid climate. Though this is the same species from a botanical standpoint, their ecotypes adapted to completely different environments. This information is not at all taken into account by nurseries when they sell their trees because traceability is lost. The plant was propagated in the Netherlands before traveling to Italy, Germany, or France, without the possibility of retracing its ecological aptitudes linked to its provenance.

Depending on where its parent plant comes from, a specimen will be acclimatized or not, though the species is one and same. It isn’t therefore enough to simply identify the tree species that are well adapted to climate change, their various ecotypes must also be considered. In terms of varieties, can a maple from Montpellier, tolerating heat well, be considered “local” in the Parisian basin or the Lyon region for instance though it doesn’t grow there spontaneously? Because it isn’t “native,” should we avoid planting it, though the variety has a high adaptive potential? And, deep down, what does “local” even mean in a nature that isn’t static? Take the peach tree: every garden has one and it is widely considered a “local” tree, and yet its Latin name is Prunus persica, in reference to Persia, which was widely believed to be its original habitat. It is a known fact that Alexander the Great brought it back from the Middle East to Greece, and the Romans then introduced it to France. But recently, it was discovered, thanks to advances in genetics, that the peach tree actually hails from China. This species had already traveled as the result of trade that had occurred in 2000 BCE between China and Persia. Its history is a cultural one and is closely connected to that of humans. The same holds true for wheat, walnut trees, locust trees, cherry trees, and a wide range of animal and plant species that were imported to serve human needs over the centuries. Invasive plant species have now become an important matter in discussions regarding the planting palette, but “exotic” plants shouldn’t be confused with “invasive” plants. There is an untold number of “traveling” plants across our landscapes, which pose no risk and flowers that can be pollinated by our local insects.

The urban landscape is, in essence, a consensus between nature and culture. It was shaped by human culture and history, and it is important to reintroduce this dimension in the way we will design the landscapes of tomorrow. The future of our flora lies in our ability to extend the planting palette of our landscapes by well-thought-out introductions of plants with high adaptive potential.

This article was initially published in STREAM 05, in 2021