The title of your book appears to be an oxymoron if one considers that what is artificial cannot be natural. How do you then define “natural artifacts”? Do the changes occurring in the world today, in particular in terms of the environment and technology, invite us to consider that these two extremes are coming together?

What emerged from the many publications I have read on environmental philosophy—American texts in particular—was that there was always a lot of fuzziness regarding objects that are created by man but that are akin to nature. We find it very hard to define them but also to clarify their ethical and political context. For this reason, I started off from a very basic question: “Are there any non-natural things?” The first and obvious answer to this question is of course affirmative, though it is extremely difficult to differentiate what proceeds from “nature” and what proceeds from human action. Tim Ingold came up with a very interesting thought experiment: which objects would aliens from outer space identify as being natural or artifacts, and what criteria would they use to draw this distinction? The first criterion would be whether an object had been made by a human being or not, which is counterintuitive given that it implies that human beings are incapable of producing natural things and that they therefore are not a product of nature. There is in fact no reason whatsoever to view ourselves as being super-natural and not forming part of this oneness.

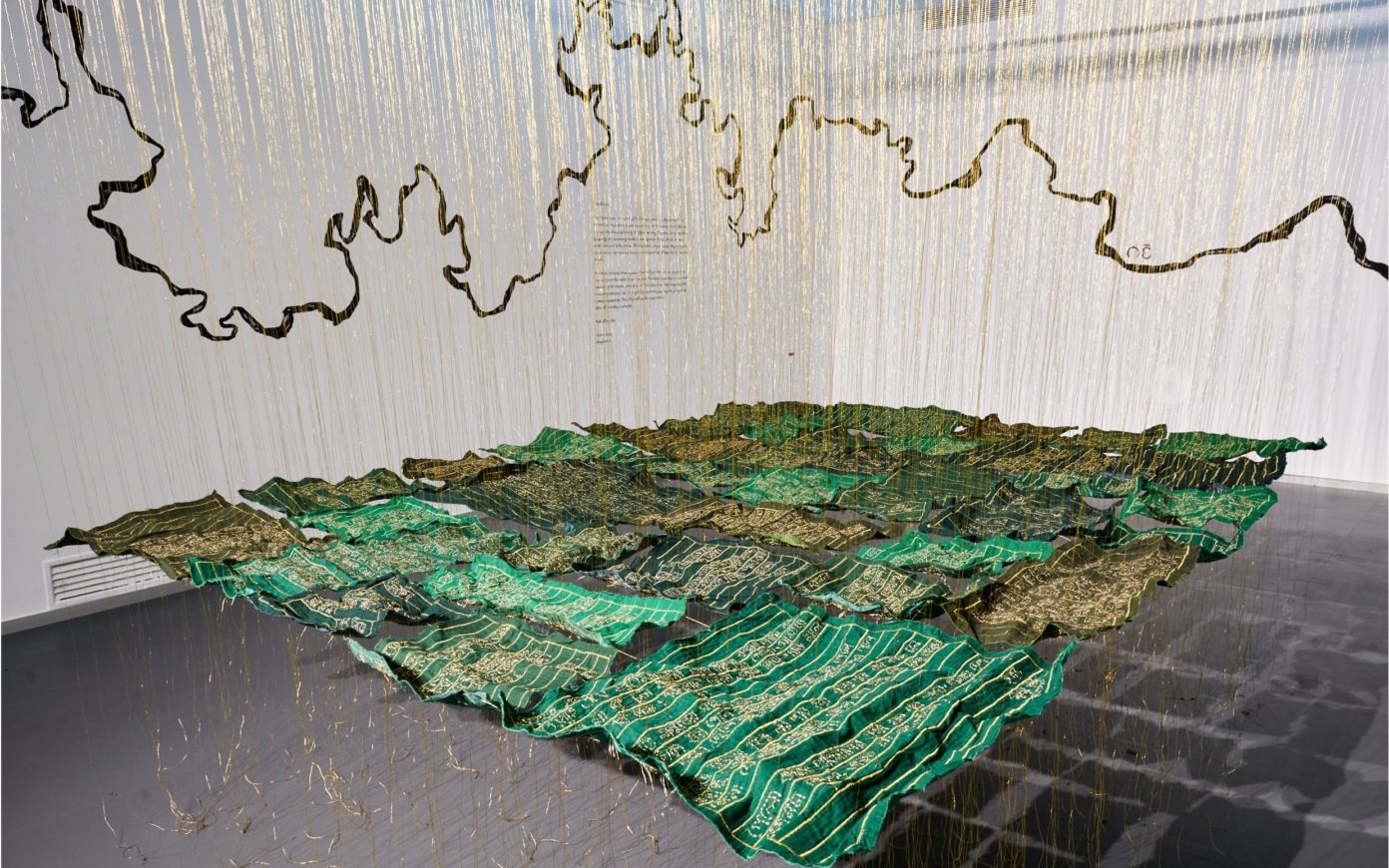

It is extremely difficult for instance to differentiate a beaver dam from a basket that was woven by a human being. In both cases, there is a natural material that is “woven” into something. What makes the beaver dam and the basket different is simply the essence of its maker—an animal in one instance, and a human being in the other. I find this difference to be rather modest, hence the use of the word “natural artifact,” which I defined as being “an entity that has been deliberately created by human beings yet that may be akin to natural processes and that has a potential for autonomy.” Not all objects created by humans are therefore covered by this definition, but only those that are akin to natural processes. To give a counterexample, a sky slope in Dubai is a form of natural landscape that is created by man but that is not part of any form of continuity given that it is inconceivable that there would be any snow in the United Arab Emirates; it can therefore not be a natural artifact. Conversely, a patch of forest that was replanted by human beings but that has a morphology that is comparable to that of its surroundings has a potential for autonomy; it can gradually move away from human influence and exist on its own and, as such, it qualifies as a “natural artifact.” Three principles guide the creation of natural artifacts: a reality principle (opposed to that of “super-naturalness”), a principle of autonomy, and a principle of continuity with nature (opposed to that of “un-naturalness”).

The idea of natural artifacts provides a way of countering a common fallacy, pervasive even among environmental groups, according to which any human intervention in nature is intrinsically negative. The argument of design is commonly put forward: the idea that a form preexists in the mind of its builder before being reproduced in nature is a problem for many thinkers. It implies that anything human beings design can only be anthropocentric. Human beings would therefore be unable to create or think up anything that could benefit other living beings. There are indeed a wide variety of examples of adverse human interventions in nature, yet this should not prompt us into believing that any human action is intrinsically negative. This would indeed mean that there is no place for humankind in nature and justify getting out of it entirely, which is an idea I find particularly egregious because it suggests that human beings aren’t a part of nature. Policies aiming to recreate a virgin wilderness come to mind. Natural parks are of course beneficial in many ways, but they are also conducive to many excesses, for instance when humans are deliberately kept out of certain ecosystems. In a time of intense environmental crisis, it would be a fundamental error to consider that human beings have no place in a natural system. On the contrary, I believe it is important for humanity to become more involved with nature by increasing the number of hybrid objects, i.e., natural artifacts, which allow all of us to form nature, learn from it, and get closer to it.

Are natural artifacts changing our relationship to the living world by fostering a closer relationship to nature? What prospects does this open up in the environmental and political spheres?

The key role of natural artifacts is to create a special relationship between humankind and nature. To create an object that is akin to nature, it is crucial to understand its underlying model. Likewise, to recreate an ecosystem, we must not maintain any distance from it but rather plunge right into it. This connection to the environment, midway between involvement and attention, is quite similar to gardening. There are different approaches to gardening, but the principle of care and responsibility are a necessary part of gardening and they must guide us in our relation to the environment. It is true that humans are constantly intervening in their gardens, yet they also largely tend to follow a precautionary approach, which is something I feel must absolutely be included in the definition of a new relation to the living world. In the era of the Anthropocene, now that humankind has become the main geological force acting on nature, it is essential that we live up to our responsibility toward other living beings. Hans Jonas, one of the first thinkers to have really taken interest in environmental philosophy, defined the imperative of responsibility as a future-oriented ethics. He argues that we must act so that the effects of our actions maintain the integrity of the natural environment and prevent future disasters, and offers the precautionary principle as a way of addressing these concerns.

The debate on environmental restoration is a highly symbolic one. Many people believe that to restore an ecosystem that has been damaged by human beings or a natural disaster, it is crucial that it should be restored to its former self, which implies arbitrarily choosing a historical benchmark. Others would rather invent something completely new through the use of technology. In the United States, there is a tendency to aim for an untouched “virgin wilderness,” similar to what had existed prior to the arrival of the first European colonists. This rhetoric of restorative nostalgia is imbued with politics however. We must not lose sight of the fact that the way we project ourselves on the living world reveals the way in which we would like to position ourselves on a cultural level. Nature is sometimes used to erase or to cover up certain periods of human history.

In your book, you clarify the concepts of “restoration,” “rehabilitation,” and “rehabitation.” In your work as an advisor to the Deputy Mayor of Paris, Jean-Louis Missika, did you see any practical applications to these various theoretical ways of embedding or restoring nature in an urban context?

We cannot address the concept of natural artifacts without examining the distinction between city and nature. If we consider that a “virgin wilderness,” with no humans allowed, is not a solution, then it is not possible to conceive of cities as being reserved for human beings either. This is a relatively common view however, that of the city as a place where the presence of animals is made invisible or is even rejected. However, the greening of cities, the development of urban agriculture, and the issue of urban food supply are gradually softening the perceived unequivocal opposition between city and nature. It now even appears obvious that we cannot view cities as self-contained units anymore.

The concept of natural artifacts is an important part of my practice. Each building must be seen as belonging to an ecosystem in which other living beings can find their place and where a great variety of possible interactions must be imagined. It is critical that each opportunity to create varied ecosystems within the urban fabric be seized. No city ever loses anything from being reintegrated by nature. Paris is often presented as a mineral city, and, admittedly, part of the natural environment was eradicated, among other reasons due to the sanitary movement of the late nineteenth century, but that is but one moment of its history. Paris hasn’t always been like that, and other periods could be chosen as a reference, times when nature was more widespread and present in the everyday life of Parisians. This way of thinking about time must really guide our day-to-day undertakings.

It is interesting to consider the issue of environmental restoration from the vantage point of artistic or architectural restoration. The question of whether to return to an initial state or to reinvent something new that would be inspired by the past but forward-looking is very much the same. The notion of rehabitation refers to the fact that it would be fictitious to replicate the past given that things in fact change over time. Recreating an ecosystem from the past in a new context amounts to transforming it into a sanctuary. This deprives it of possibilities of interactions with those living beings that have progressed in the meantime. The same goes for buildings and works of art. Rather than restoring them, rehabitation seeks to create an interaction between an ecosystem and the players within it, usually humans, that wish to learn from it. Given this educational value, I find rehabitation more important than rehabilitation or restoration, where the idea is to reproduce something that often never was and that we would like to see exist just as we dreamt it up.

Beavers, ants, and other animals are continually modifying their habitat. We are therefore not the only ones to design places. Bird galleries and burrows are substantial structures that modify their immediate surroundings in the same way as human architecture does. It is a mistake to consider that nature is static and that only human beings transform their habitat. Human action must always be viewed in the continuum of the other natural living beings, in particular through the issue of habitat. Architecture and urban planning, whether it is the creation of the “cocoon” or residential unit, must consider how these will form part of the natural environment, just as happens in an anthill.

We must also abstract ourselves from the idea that human-driven environmental modifications are necessarily detrimental to nature and beneficial only to human beings. In the same way that soil quality is the result of the work of a huge number of living beings, earthworms in particular, it is crucial that we take heed of the fact that human creations extend beyond the anthropocentric. We are perfectly capable of developing ecosystems in order to make them beneficial to many other living beings. This is the job of landscape planners, architects, urban planners, and all other participants in urban development. They should be taking on the role of ecosystem experts to weave new habitats by creating small nests and hideouts that can be useful to other species.

order the book-magazine