Reshaping myths to reveal pressing realities

- Publish On 17 January 2025

- Ashfika Rahman

- 18 minutes

Ashfika Rahman is a visual artist based in Bangladesh, who recently won the Future Generation Art Prize awarded by the PinchukArtCentre in Ukraine. Faced with the overwhelming power of information systems that are serving dominant narratives, she is working on creating alternative medium of expression, giving their voice back to marginalized communities in her homeland, particularly women. Through her art, Rahman questions myths, folk tales and widely spread prejudice that are still shaping our cultures and legitimating violence, adopting a contemporary and feminist lense. We met with her to discuss her recent work, Behula These Days where she brings together ancient crafts and new techniques to share the poignant and heart-wrenching experiences of women living in one of the most floodprone areas in Bangladesh.

Stream Voices: Behula These Days is a powerful and feminist artwork, confronting the legend of an absolute love to the painful lives of women in your homeland. Why drawing inspiration on this myth in particular?

Myths and legends, passed down through generations, hold immense power. They perpetuate narratives, thus giving birth to idealized representations fostering a status quo that can resist change or stifles progress. At their worst, these narratives can become instruments of violence, stripping individuals or communities — because of their gender, beliefs, culture, sexual preferences or skin color — of their right to tell their own stories.

The tale of Behula, one of Bengal’s most renowned mythological love stories is one of them. In the plot line, written between the 13th and 18th centuries, Behula’s husband loses his life on their wedding night because of the curse the Hindu goddess of snakes had casted on his bloodline. In the hopes that he could miraculously be brought back to life, Behula accompanied her husband’s dead body on a raft towards heaven, facing many challenges and dangers. Once in heaven, Behula pleased the gods with her beautiful and enchanting dancing and earned her husband’s life back. Still today, Behula’s devotion and determination to save her husband’s life are regarded as the epitome of a loving and loyal wife in Bengali culture. Upheld as an ideal for womanhood, Behula’s tale has been instilling unachievable expectations, generations after generations. The legend’s influence appears most strikingly in the gatherings of people around the river to honor her story, perpetuating ideas that constrain women’s autonomy.

In my project Behula These Days, I sought to question and transform this narrative through a feminist lens. Even though the snake goddess is portrayed as the villain in the legend, she was, in fact, denied devotion because she is a woman. Misogynist views are thus what really caused Behula’s misfortune, leading to the suffering of two women — a human and a goddess. Painted as the antagonist, the snake goddess embodies the very patriarchal injustices that continue to resonate today. This re-examination invites us to challenge the legend’s mainstream interpretation and its pervasive influence on contemporary Bengali society.

To create alternate narratives, I embarked on a journey along the same river Behula once traversed, collecting the stories of women whose lives are still shaped by these unattainable ideals. I listened to harrowing stories: a Hindu woman humiliated in public for loving a Muslim man; another killed for failing to bring dowry; a young woman confined to her home because she aspired to study abroad; and yet another condemned for her darker skin tone, subjected to servitude before being murdered and thrown in the river. Each story bore the weight of societal expectations perpetuated by Behula’s legend.

Stream Voices: how do you use these stories as a canvas for your artistic project without altering the voices of the women you met alongside the river?

This is indeed an ethical dilemma: how can I craft alternate narratives when I am not part of the communities that are suffering? Ultimately, I decided that I have the right to engage with these issues as a human being expressing solidarity with oppressed people. However, I also recognized the importance of ensuring that my work amplifies their voices, not mine. My role as an artist became clear: to collaborate creatively and provide a platform for them to express their truths. My intervention thus centers only on creating the best medium for them to express themselves, using my artistic expertise: this is the only form of collaboration that would ensure a faithful translation, from reality to art.

This approach has shaped my entire artistic process: in every project I undertake, you will notice that texts and writings are present, but they are never authored by me. I also integrate the communities’ own materials and crafts into the installations we create together. Materials hold profound significance, as they are inherently political. Every thread, every fabric carries a narrative. For example, a textile produced in Bangladesh reflects the country’s labor policies and its geopolitical positioning in the world. Therefore, in all my projects, the materials predominantly originate from the community itself, whether through their belongings or traditional. Even when I use photography as a medium, I strive to contextualize it within the environment. For a project on an abandoned cinema in Dhaka, I used expired film stock from 20 to 30 years ago to document the space, capturing its decay through distorted images. I find great fulfillment in forging connections between materiality, context, and artistic expression — it’s the core of my creative practice.

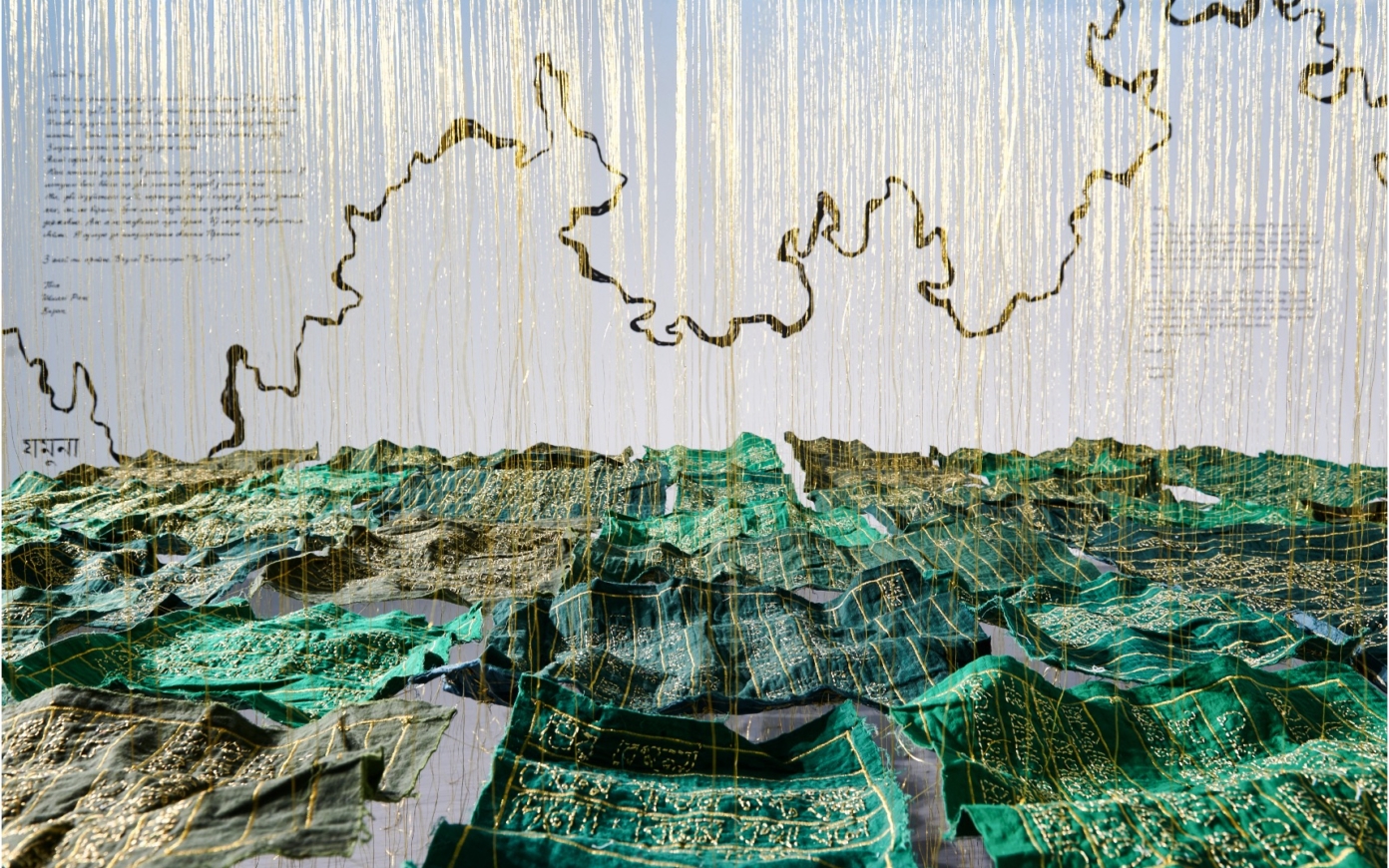

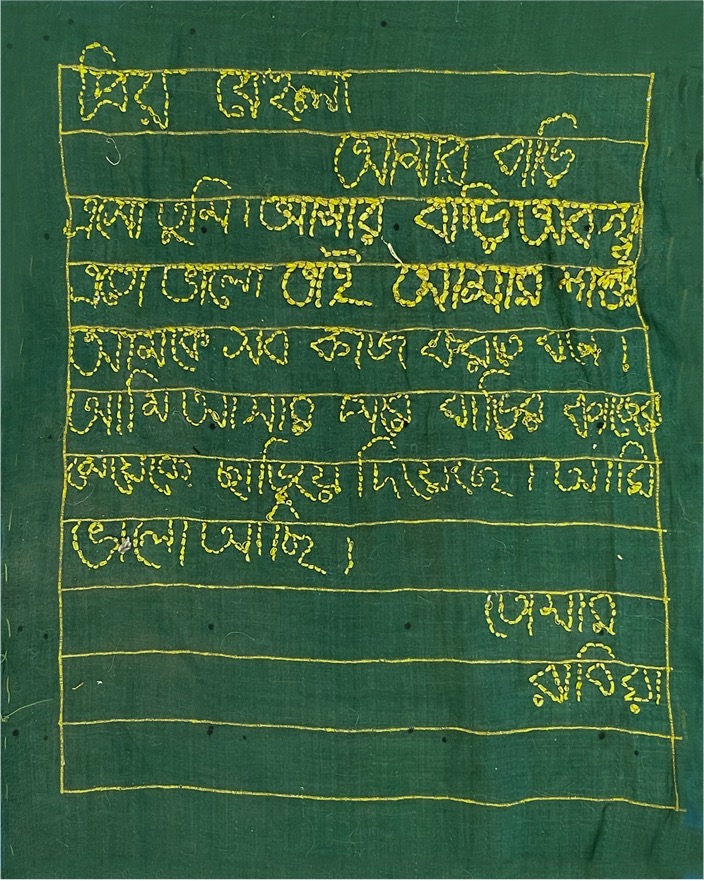

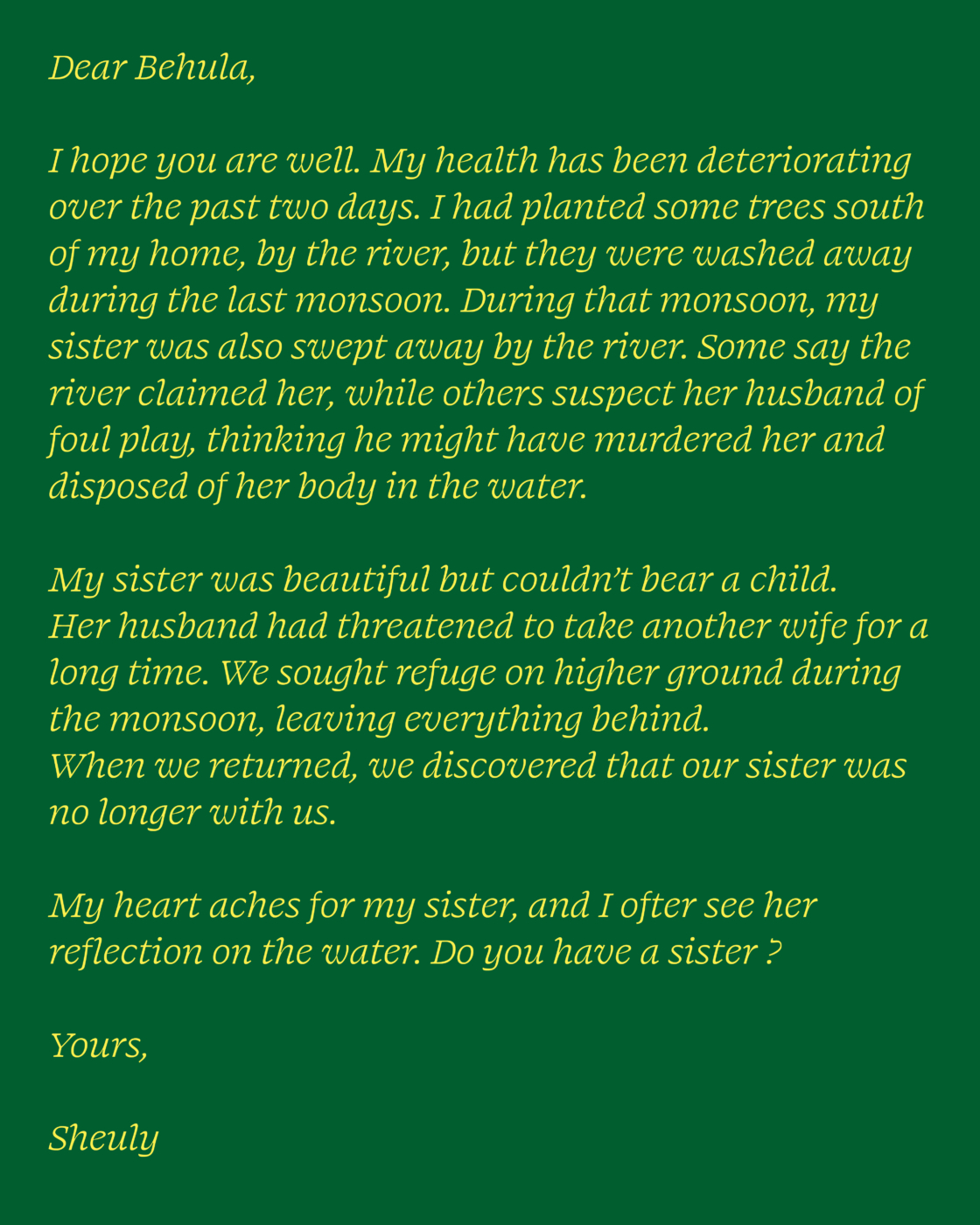

To go back to Behula These Days: how could I confront these stories with sensitivity while reconciling them with Behula’s tale? I decided to invite these women to write letters to Behula herself — a figure who, within the myth, could understand their pain and sacrifices. Traveling from Bangladesh to India, I gathered their stories, not in ink, but in thread, as stitching is their preferred form of expression and is deeply rooted in the region’s culture.

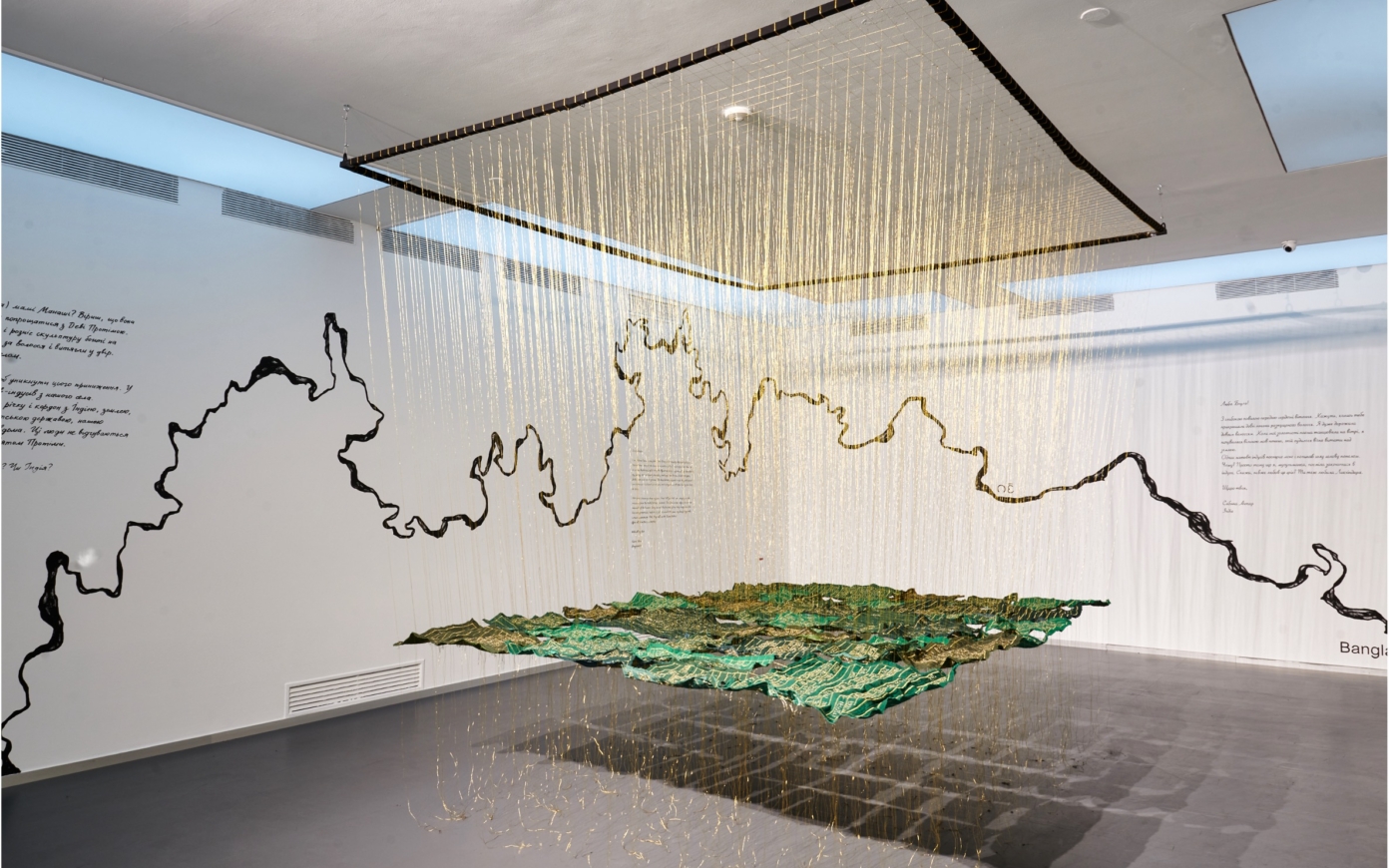

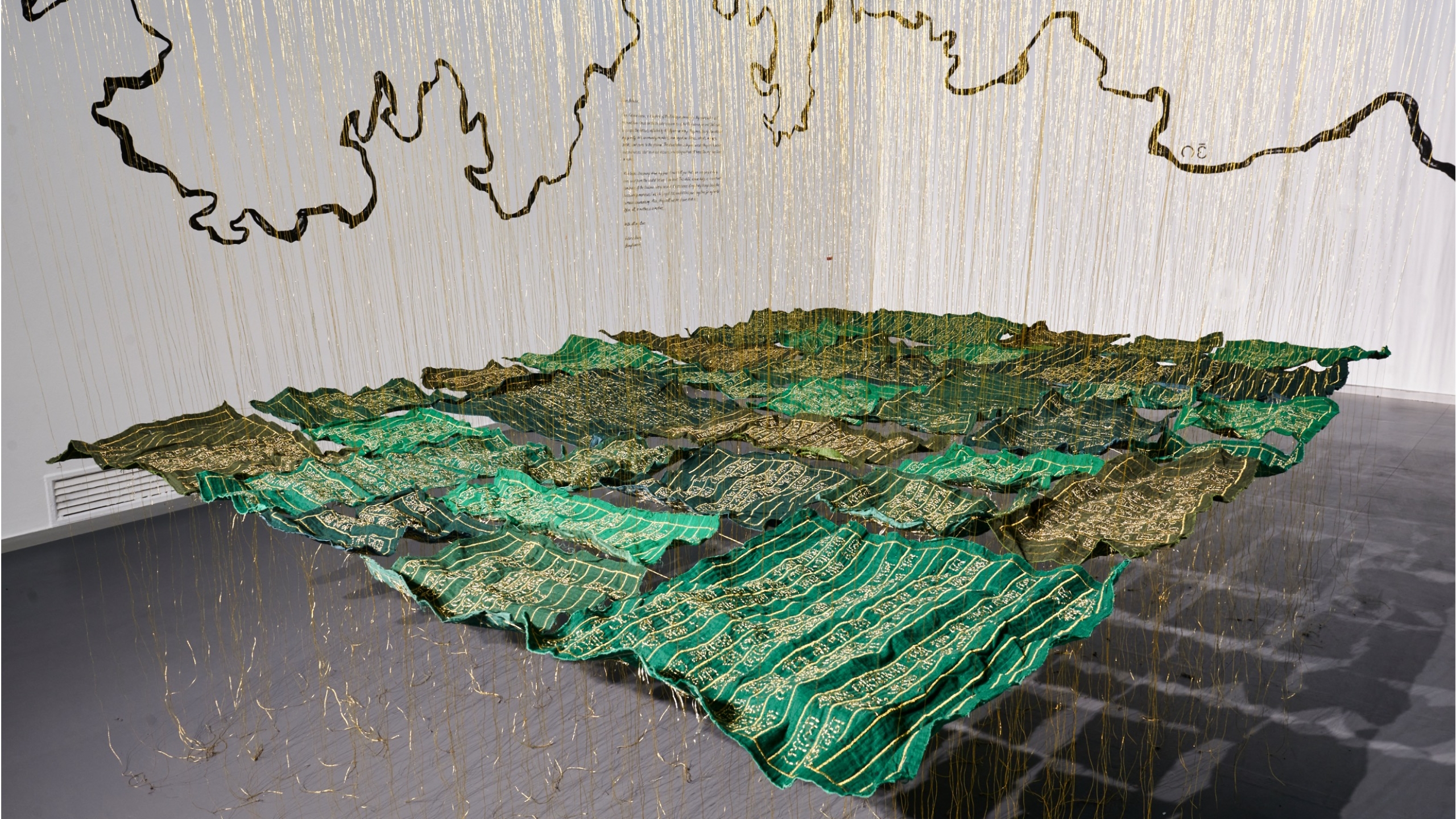

The resulting installation takes the form of a floating raft, echoing the journey of Behula while carrying the untold stories of 34 women, stitched on green fabric, symbolic of the banana leaves that formed Behula’s raft. Only attached to the ceiling through very thing golden threads, the green raft seems to be suspended in space, drifting perpetually, its stitched letters forming a tapestry of resilience and solidarity. Its shadow casts an aerial map of the region, linking the artwork to its original landscape. Working as a visual metaphor, Behula These Days not only honors the women’s voices but also reclaims the myth, transforming it into a vessel for empowerment and change.

Stream Voices: we discussed how narratives hold a great power on communities, influencing our beliefs and representations and how you are trying to infuse change. How can we navigate through these stories when we are all surrounded by an overwhelming number of narrative vessels, such as social media and television, conveying dominant views?

It is indeed getting increasingly hard to have access to alternate narratives, especially when social media, newspapers and televisions are relaying prevailing ideas that are serving the interests of a dominant political, cultural or societal class. Of course, narrative vessels can also be used as a platform for otherwise muted voices, but being heard when you are part of a marginalized community is still extremely difficult. This is what I found striking with The Power Box project. It began as a typological survey of televisions in the villages of Chalan Beel, the largest wetlands of Bangladesh. Not only are these people marginalized by their remote geographic location, but they are even more isolated during the very long monsoons, when circulating on the river is the only way to get around. They use solar power to run black-and-white televisions, which are broadcasting only one state-owned channel that does not require satellite.

The villagers are thus not only presented with only one narrative, spreading the state propaganda without question or criticism, but because only a few houses in the village are equipped with a television, whoever owns one holds the most power in the community. People come to the television owner’s home to watch it together. Usually, the owner sits on a chair or somewhere comfortable, while everyone else sits on the floor or even outside in the garden. This intricate chain of power — from the state propaganda to the television owner — has profound consequences on the whole village.

Television plays a vital role in their community: it creates a ritual and helps with social bonding through a unique narrative: in a way, televisions are literally ruling their reality. I documented this dynamic through a series of photographs. Although televisions are an alien element — a window on the world, but a very narrow one, showing one reality only — they are entirely integrated into the households.

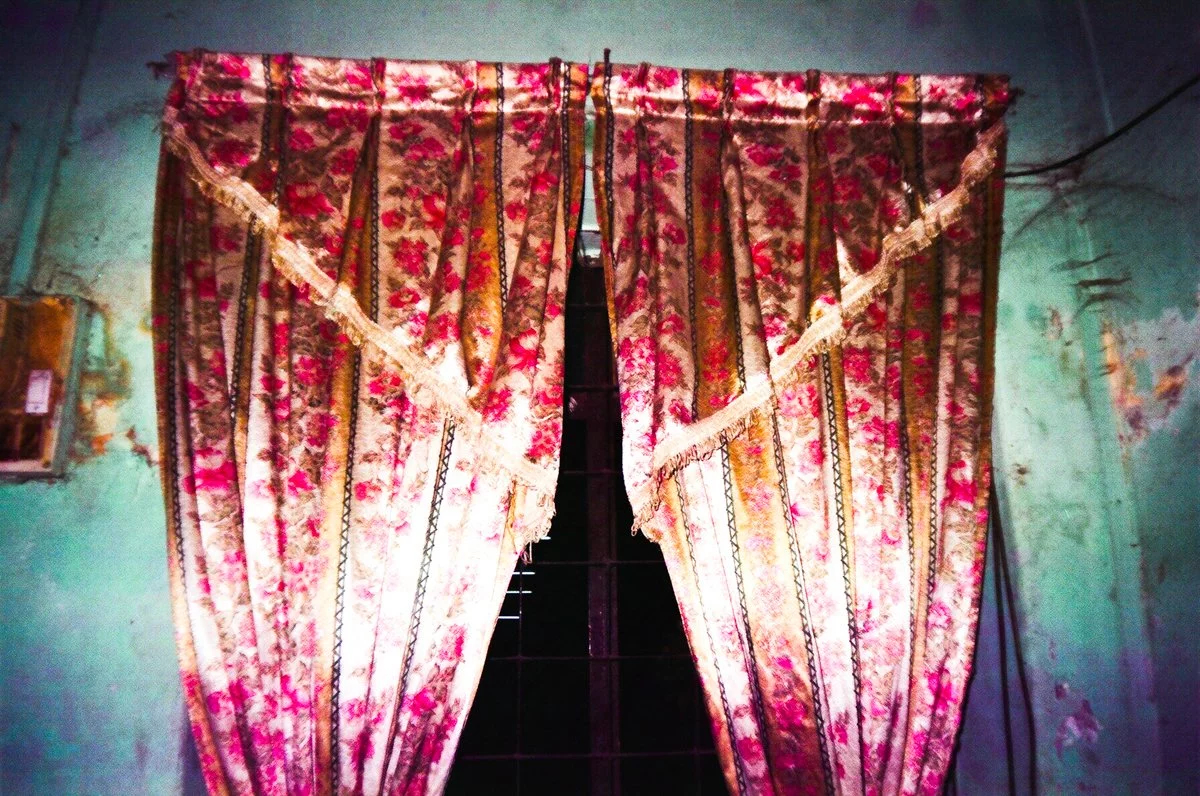

Families treasure them as their most precious possessions, decorating them using their own saris or other belongings, becoming one with the household aesthetic. The televisions are always placed on top of something, elevated as if on a pedestal. Because it’s a Muslim-majority country where watching television is sometimes frowned upon, they cover it with fabric, much like how one might cover the Quran. To me, this metaphorically represents how information systems rule the world today. Newspapers like The New York Times or broadcasters like the BBC, and even social media platforms, hold immense power — and responsibilities — to shape perspectives. This village’s relationship with television reflects, in a microcosmic way, the global information system.