Sustainability with a hammer

- Publish On 2 January 2017

- Franck Boutté

Are the current standards in the environmental fields judicious in a world consisting of a variety of contextual changes and versatility? Environmental thinking on formal provisions of increasing complexities, forgets that further energy is produced by ecosystems of offices such as social, creative, and other dynamic transformations. Within his projects, Franck Boutté has developed a philosophy of sustainability «with a hammer.»

Franck Boutté is an engineer. He is the founder and director of the environmental design and engineering firm, Franck Boutté Consultants.

Olympe Rabaté is a former student of the Design department of the École Normale Supérieure de Cachan and an agrégée specialist of Applied Arts.

«There are altogether no older, no more convinced, no more puffed-up idols—and no more hollow. That does not prevent them from being those in which people have the most faith.»

Friedrich NietzscheFriedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of Idols, How to Philosophize with a Hammer, 1888, Trad. Henri Albert.

The hyperrealism of the contemporary environmental condition

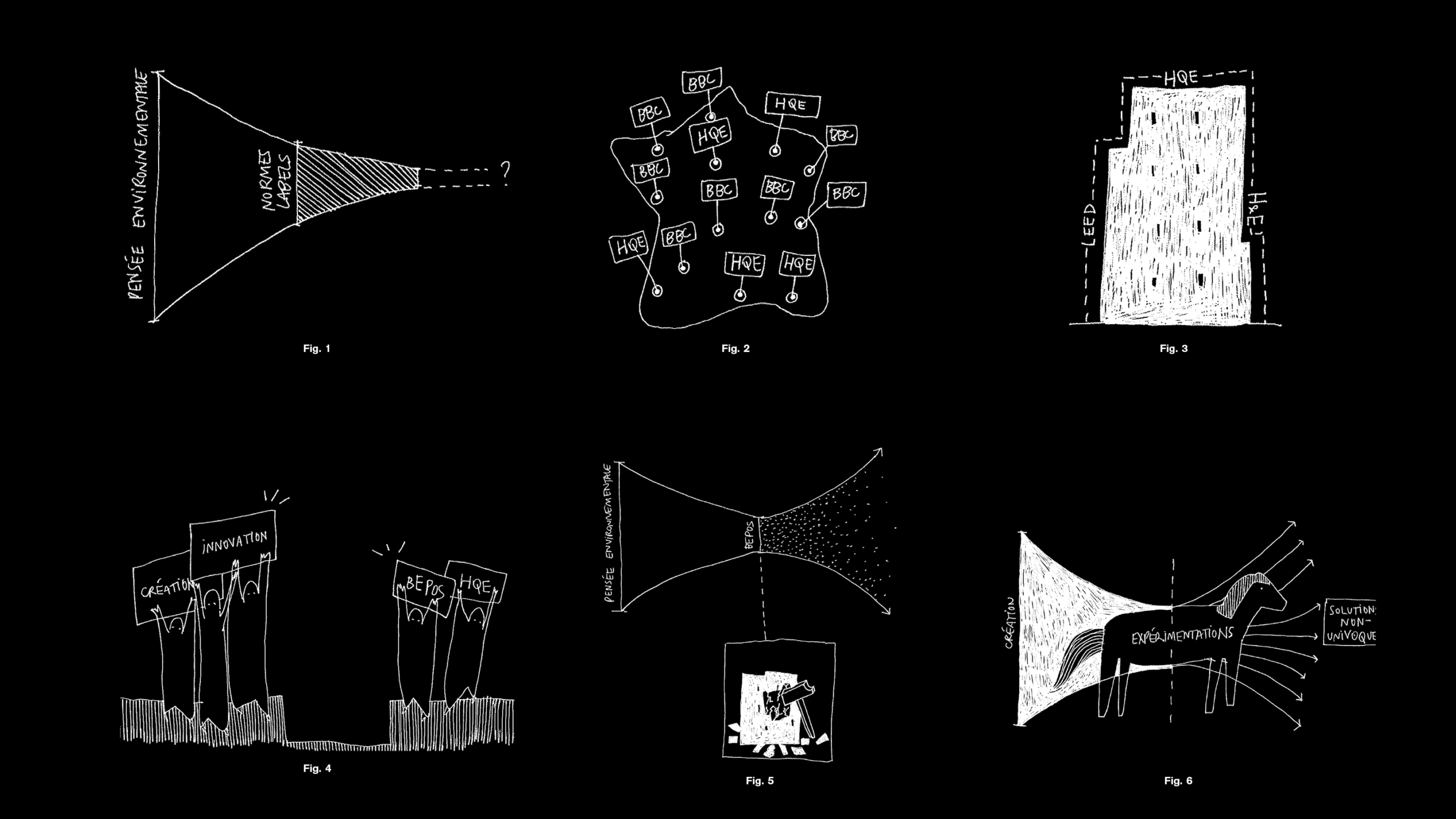

Contemporary environmental thinking can be likened to a funnel. (Fig. 1) At its outset, it is open and revolutionary, gradually hammered down under the pressure of environmental assessment methods and rating systems. Profoundly innovative in its beginnings, advocating a radical shift of paradigm, this thinking weakened until it became a hollow dogma, closing the door on any possible invention. At its core, the metaphorical funnel of sustainable development is wide: it welcomes all ideas, all disciplines and all discoveries. It offers a complete rethinking of how to produce, to dream and to create. And then it narrowed when laws were used to prescribe guarantees of compliance and number goals. At its end, the funnel is only a narrow path without perspective or light. Sustainability needed to comply with unambiguous solutions. But in terms of a global ambition, triple glazing or eight inches of insulation provide a disguise. Labels and certifications, reference texts written off-site and out of context, kill environmental thinking. They lock them up in poor and preconceived solutions, often totally unsuited to real needs. (Fig.2)

At the heart of the magazine Stream, one can find all the current conditions of architectural commissions. They dictate that projects fit into a legislative and administrative framework. Ecology is a political reality; the depletion of resources an economic argument. If we take the idea of Lacan, «production», like reality, «is when one hits oneself.» It is this which marks the contours of the possible and the impossible. «Creation» is fed by the imagination; it is this energy that guides inventors of all kinds. It is limitless. It allows itself to dream of the absolute and to fantasize about a perpetual questioning of established patterns. Creation evolves in a propensity for innovation and renewal. At the junction of the real and of the imaginary, part of contemporary architecture seems to have chosen the way of realism, or even, hyper-realism. Rather than inventing a new compromise between the binding conditions of production and innovative ideas, it embraces prescribed solutions without blinking. The environmental standards HQE, H&E, BREEAM, LEED, confine the narrow contours of an architecture, one that is terrified of not obtaining its sacrosanct certification. This hyper-realist conception is transforming simple tools or transient models into real idols. (Fig. 3)

Voluntarily or involuntarily, those buildings have worsened reality itself, freezing and exacerbating it. Instead of trying to transform it, they idolize it and display it. They are the product of figures that do not accept questioning. BEPOS, BBC, HQE, BREEAM, LEED are shields that developers, politicians and designers brandish to justify the validity of their approach. (Fig. 4) The actor of the production says to the architect: «We must do that» and he or she obeys without batting an eye. Why do they not answer: «Until proven otherwise?» The end of an intelligent environmental approach cannot avoid innovation and must challenge established patterns. Temporary and ad hoc solutions cannot become universal standards. In order to open up the narrow impasse into which sustainable development has sunk, we must advocate a hammer-blow philosophy (Fig. 5): break down current idols so as to «devise non equivocal» work methodologies; manufacture experimental operations in the form of a Trojan Horse. If they are sufficiently relevant, they will submit the «production» to «creation» and allow a change in direction. (Fig.6)

Finally, the hyper-realism of the contemporary environmental condition is in the grip of a major peril. In a desperate desire to override nature—inherently indeterminable—and man’s relationship to it, what resolutions can we not undo? What strict landscapes are we drawing without thinking to a future and a necessary evolution? What values are we outlining and what project of society do we wish to uphold?

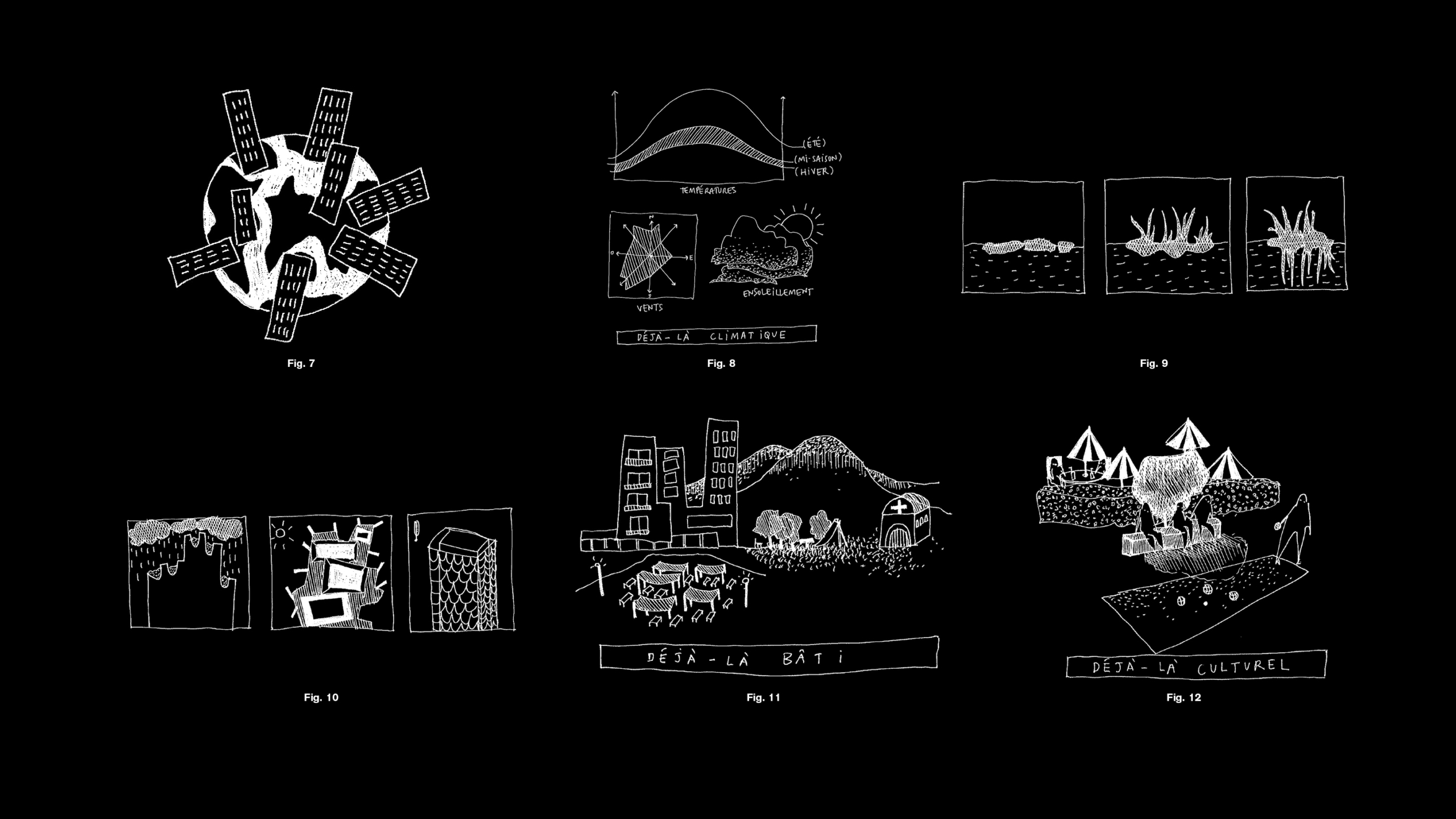

The architecture of the five «pre-existing» and the three ecologies

Local solutions in a world of global offices. That’s how the challenge of business sector architecture could be summarized. Indeed, companies have gone global, their subsidiaries spread around the world and their real estate assets scattered. Most often, it is in the unity of architectural forms that companies seek to build their identity. This need for cohesion may go against the diversity of approaches, specifically an ecological design called endogenous. (Fig. 7) Moreover, the standardization of environmental norms, not taking into account the geographical location where they apply, leads to draw a landscape of exogenous buildings.

The endogeneity of a project is measured by its method of dealing with its environment, with the existing or more generally with the «pre-existing». The first «pre-existing» is that of climate: temperature variation, winds, their direction, humidity levels, cloud cover… (Fig. 8) To develop sustainable offices is primarily to anchor them in a climatic context in which they are shaped. This is to rethink how we design buildings based on geographical and climate «pre-existing» conditions. Morphogenesis draws a parallel between building design and the process of natural development of a living organism. Constantly adapting to its environment, an animal or plant invents its own forms to sustain it and to survive in a more or less hostile environment. The morphology, the skin and the organs are the result of a dialogue with the environment in which they have evolved. (Fig. 9) Although this is evident in biology, it is not yet the case neither in architecture nor in urban planning. If one thinks in terms of the morphogenesis of the structure, materiality, spatiality or systems of a building or a city, it becomes impossible to work out of context and without considering the «pre-existing climatic» element. (Fig. 10)

Other «pre-existing» elements should also profoundly influence how projects are conceived. The «pre-existing construction» element takes into account the heritage, the existing fabric, the views on the immediate environment and everything related to urban planning, architecture and landscapes. (Fig. 11) The «pre-existing cultural» element focuses on practices, lifestyles, beliefs and on all the creative and artistic dimensions of the site. (Fig. 12)

The «pre-existing economy» element includes existing sectors, implanted industries and local actors able to produce new synergies. (Fig.13) The «pre-existing energy»element identifies available networks, the development potential of certain sectors, as well as the ways to produce at will. (Fig. 14) There are obviously an infinite number of «pre-existing» elements so that it is necessary, with the aid of strategic site analysis, to uncover them to ensure the endogenous nature of each project. (Fig.15) The idea of morphogenesis must extend to all areas of activity and feed projects according to a philosophy that seeks the right amount of effort for the best gain. Based on the different «pre-existing» elements, it is possible to sketch the outlines of commendable, efficient and pleasing buildings. Identify the existing provisions, gather the available forces and use locally available resources can greatly reduce the effort required. The climatic, construction, cultural, economic and energy elements of a project link it in a sustainable way to the area in which it has been located. (Fig.16)

Although the ecological model can be seen as much more advanced in the Nordic countries than elsewhere, it should not be applied everywhere. We therefore propose to identify three major ecologies according to climate zones, the «ecology of the North», the «ecology of the South» and the «ecology of the Middle.» Each carries its own issues and challenges, and requires specific responses to its programs. The ecology of the North is concerned mainly with winter comfort, how consumption of heating should be reduced and how passive solar energy should be increased. In this type of climate, the focus is on creating a hermetically sealed structure. The underlying model is that of a thermos: an optimal insulation which limits any contact with the outside. (Fig. 17) The ecology of the South seeks to control in the first instance the summer comfort, manage its need for cooling and protect itself from direct sunlight. The underlying model is that of the Roman villa: cool, shaded and organized around water sources (Fig. 18)

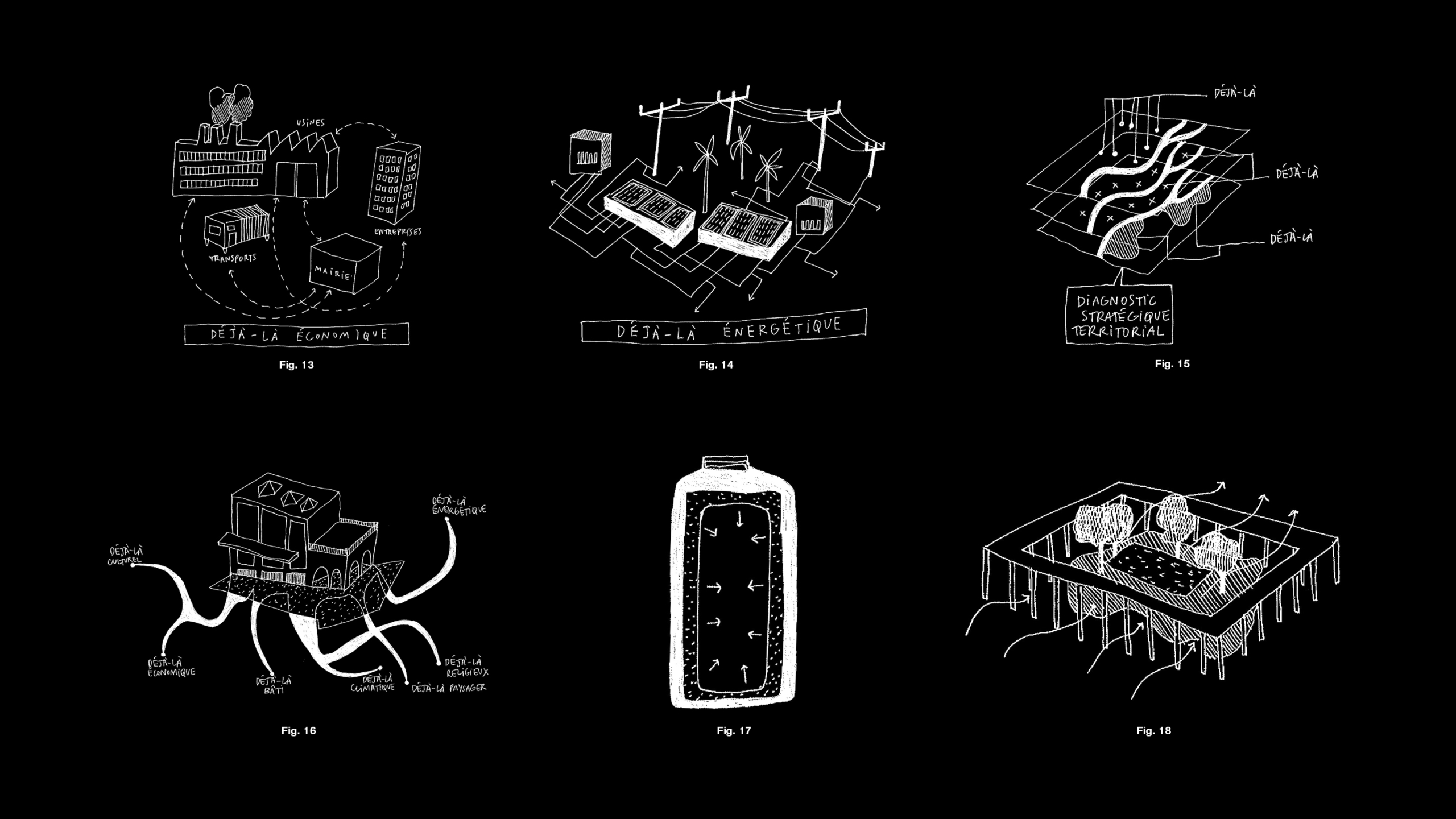

In the ecology of Middle, the main challenge is to extend the mid-season to reduce active utilization of HVAC systems and to benefit from a temperate climate, neither too hot nor too cold. The underlying model is that of coal: at once dense and porous to respond effectively to the moderate changes of seasons. (Fig.19)

In office design, the «problems» are often the same: overheated interiors, large areas of exposed facades or roofs, high consumption of power and the mono-functionality of spaces. If one thinks of office buildings as «bioclimatic machinery», we can reverse the logic in place. For if the classical architecture of the office space is to «create» a bubble of a desired indoor climate independant from exterior climatic context – the «perpetual spring» created by the alternation of heating and air conditioning – the bioclimatic design that we defend seeks to «turn» the external environment into an indoor climate, to master comfort and environments passively. (Fig. 20) By combining solutions specific to the type of ecology in which the building is implanted with the different «pre-existing» elements, it is possible to propose innovative strategies and to develop sustainable and integrated solutions.

One can contrast a «passive» building–though it is, paradoxically, dependent on many systems–to a naturally-functioning building that emphasizes low-tech solutions. Comfort, in the form of the physical well-being of its users, has gradually become standardized everywhere. Its different levels of acceptability, where a «pre-existing climate» and a «pre-existing culture» meet, have been erased. Environmental design of the offices of tomorrow cannot do without this necessary re-acculturation of user comfort. It disrupts the standards of the «office-product» and challenges the established norms. It sometimes requires the acceptance of the possible variations of temperatures within a limited time. These deviations are not necessarily negative, they can reintroduce the sensorial in a world that is more and more sleek, uniform and indifferent to the physiological needs of its occupants. (Fig.21) The comfort felt should not necessarily be equated with the level of comfort that is measured. It involves identifying the different areas of the office building by offering for example «habitat areas» or «maps of comfort» allowing the possibility to adapt the desired levels of well-being to the various spaces and their use. (Fig. 22) It is not useful to have the same quality of insulation, freshness, light, ventilation or heat everywhere. The scenarios are many and the micro-situations all different: meeting room, private office, open-space office, dining area, storage, rest area, etc . Destandardizing comfort and differentiating indoor climates are the major issues of this shift in paradigm. (Fig.23)

One of the environmental errors is to make office buildings efficient by equipping them with complex dehumanizing systems. Users find themselves dispossessed of the simple actions in their immediate work area. The opening of windows, ventilation control or the raising and lowering of blinds are automated to meet the demands that justify the certifications obtained by the building. But these calculations take little or no account of the possible needs of its users. (Fig.24)

The human element must be anticipated but cannot be predicted. To be truly effective, a building must be able to adapt to a large number of uses that had not been planned. If the systems are becoming increasingly intelligent and autonomous, it is imperative that users can retain control of them. Because after all, a sustainable office is one we want to return to the following day because it feels good.

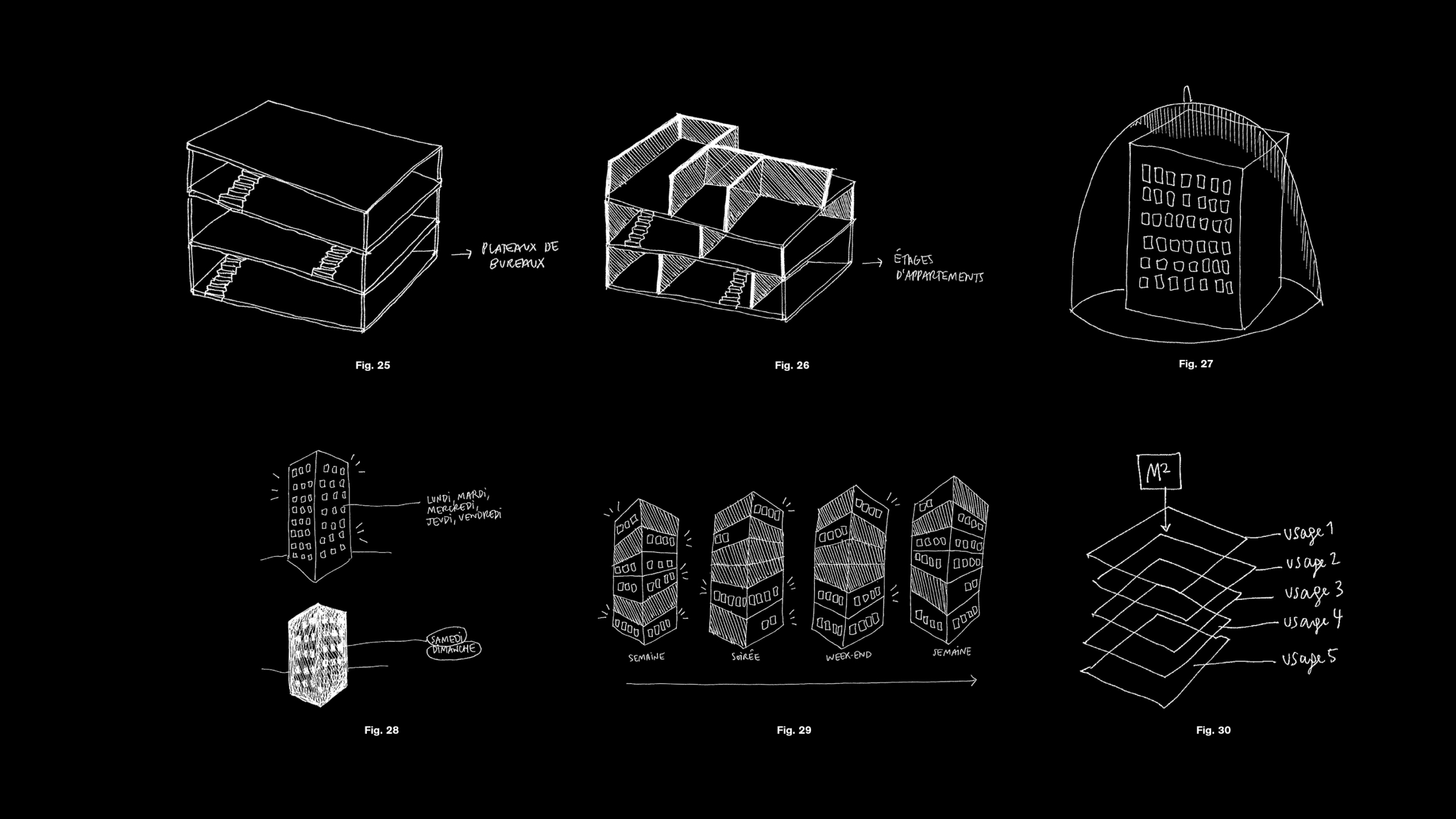

Producing office buildings that meet the points mentioned above raises another question: the appropriate balance between the specific and the generic within the city of tomorrow. The very specific cannot be a solution given the competitiveness and the economy. The most sustainable is to cross the generic with the specific in the same urban ecosystem. Offices are one of the fabrication modules of the city, on the same level as housing or sports and cultural facilities. Since it is impossible to know how long they will last, it is essential to design neutral spaces, «capable spaces», able to adapt to new uses without major changes to their structure. (Fig.25) We need to reconcile the specific programmatic requirements of buildings with flexible structures that will allow future metamorphosis. This thought of flexibility must be acted first into the design process and should become a selling point for sustainability because it can anticipate the superfluous expenditures (such as energy use or embodied energy)Energy use is the sum of the energy required—and lost— for the operation of a building and its uses; embodied energy is the sum of the energies required — and lost— to achieve the construction of a building or the production of a material. for the remodeling or reconstruction of structures not built to be changed. (Fig.26)

From the perspective of Darwin and «the survival of the fittest», experience teaches us that the «fittest» is actually not the architectural species showing off «performance muscle», but the one with the most endogenous intelligence and capacity to change.

Urban synergy and a «win-win» ecosystem

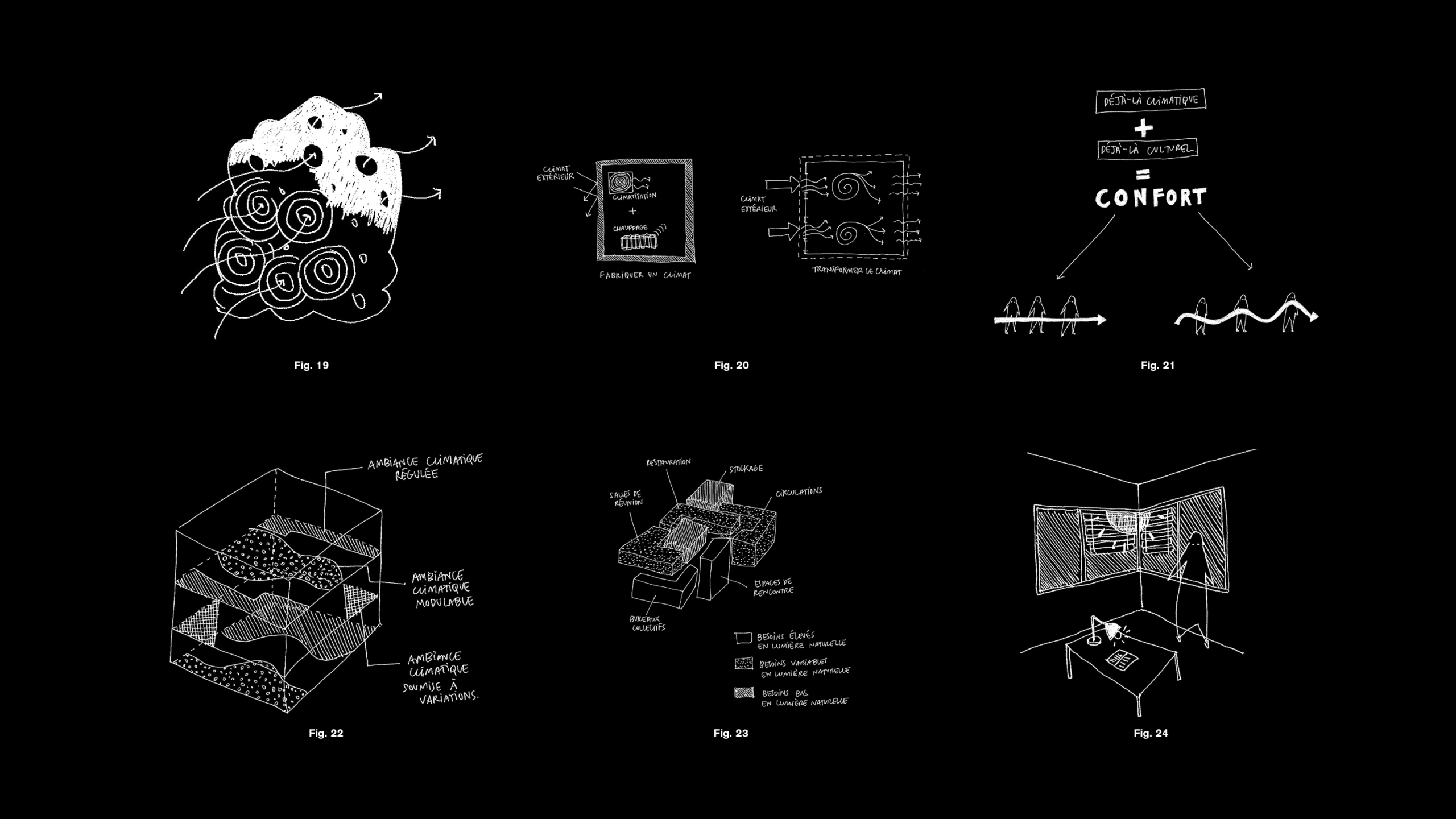

The city cannot think in a piecemeal fashion, real estate transaction after real estate transaction, building after building, one next to the other, only concerned with its own energy performance. One must adopt a holistic attitude to respond in a global way to the social, economic and energy challenges of the city of tomorrow. Designing offices in a wider connection with the neighborhood or city where they are located is also a way out of the opaque image of these places: on the one hand, in the psychological sense as the bubble in which we remain trapped all day, and on the other, the physical sense as a stand-alone capsule, sealed to climatic variations and free from relations with its neighbors, whether they be people or other buildings. (Fig.27) Mixed-use neighborhood development is too often confined to too well-meaning ideas on the beneficial social interaction that results. This idea, though obviously relevant, needs to be updated in light of contemporary energy challenges to give it a new meaning and a real weight. We state that a mixed-use develoment can truly become a piece of city that is more energy efficient, more economically profitable and therefore more sustainable.

On the scale of an office block, the mix of uses can easily become an economic argument. Indeed, buildings are too often monofunctional, «living» only during the day and hardly ever used on the weekend. (Fig. 28) Combining different activities within the same building allow the possibility to imagine an agent of life between housing, offices and facilities that share and pool their resources. (Fig.29) Increasing the economic and ecological efficiency of a site requires also thoughts on how to multiply the number of possible uses per square meter. (Fig.30)

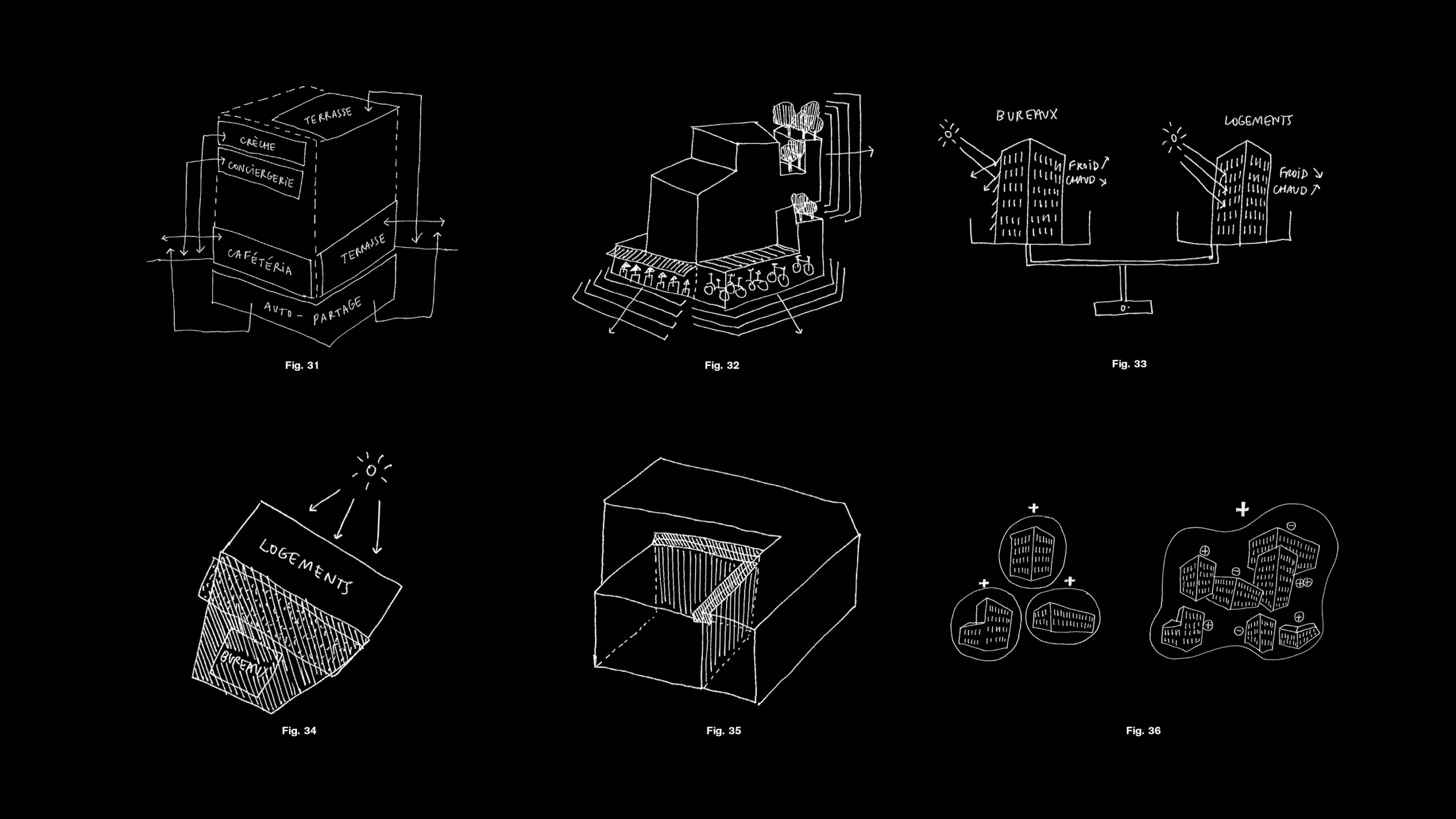

To maximize the use of spaces or of systems is a virtuous approach as it contributes to utilize better what already exists. One can imagine making use of office space when it is underutilized: in the evenings or on weekends, they would be loaned or rented out to associations and organizations in the district. Some meeting rooms or common areas could host neighborhood meetings, film screenings, music lessons, after-school activities, etc… The office building becomes a facility which benefits in a general sense people, even those who do not work there. The building can also provide services to the neighborhood. Custodial services, a nursery, a car-sharing system, a roof terrace and a cafeteria are all amenities that would benefit others when they do not benefit those who work there. (Fig.31)

In the same vein, one can imagine buildings that are more porous to their immediate environment, where the limits are thickened and made habitable. The notion of boundaries slides in this case from restriction to permission. While maintaining its private character, the building could offer broader outlines capable of receiving external activities. Bicycle parking, a courtyard or planted areas would be positive interfaces between city and office. (Fig.32)

Reasoning by energy cooperation across a district or in urban areas helps to align performance targets with realistic ambitions. Generally, offices have high demands for cooling and less for heating; they are concerned with direct sunlight and are used mainly during the day. Conversely, housing units have high demands for heating and relatively less for cooling; they like direct sunlight and are mainly occupied at the end of the day. The coupling of offices with housing units helps balance their respective needs. (Fig.33) The simultaneous implantation of both types of programs guarantee the energy performance of each of them and the comfort of their users. If one puts an office building in the shadow of an apartment building, it ensures maximum sunlight for housing while protecting the residential office space from strong direct light, which emits too much glare and is responsible for overheating. (Fig.34) With a highly efficient building just next to it, a building that is less efficient can benefit from passive insulation for free, capitalizing on the qualities of one for the benefit of the other. (Fig. 35) One could also imagine sharing heating systems across multiple buildings in order to share the costs. Finally, combining programs that have utilization times that are disparate also opens the possibility to measure in a global timeframe the energy performance of a whole group of buildings, not just one. (Fig.36)

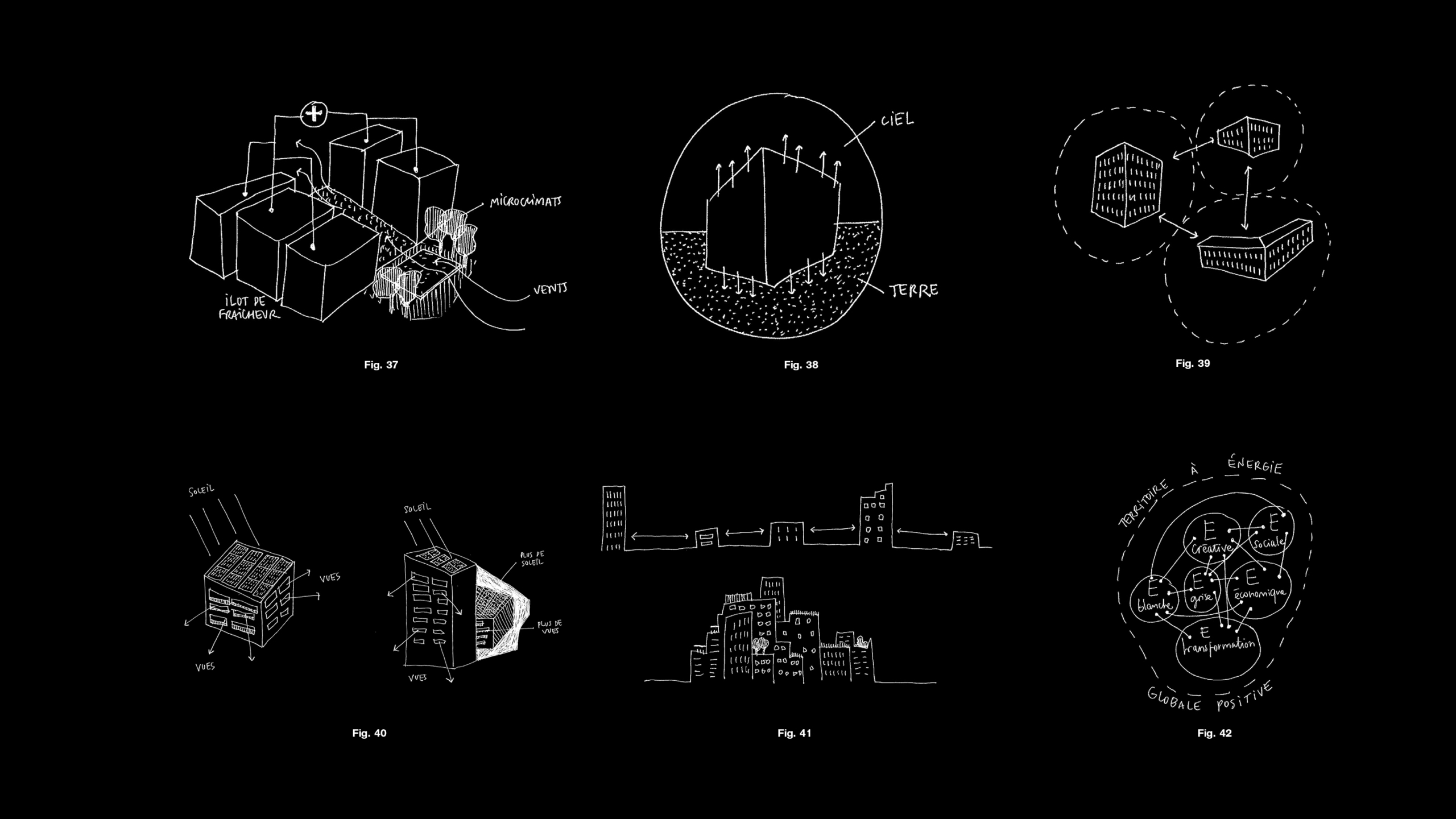

One must think of the sustainable city as a combination of programs and of needs in positive interaction with each other. As in an ecosystem, each benefits from the presence of the other in a «win-win» situation. Assessing the environmental performance of a city from each building in isolation is absurd and counterproductive. If the city seeks to build the society, why not apply a principle of solidarity with the physical elements that compose it? Offices have a key role to play in the first steps towards mixed-use development. Bioclimatic design on a large scale (cool island effect, refreshing winds, urban microclimates …) coupled with a philosophy of a balanced performance are the pillars of a sustainable urban planning. (Fig. 37)

Looking ahead to positive global energy offices

The race for certification and energy efficiency has led to the design of buildings that are increasingly autarkic. Energy 0, BBC, BEPOS are guarantees of efficiency and of energy moderation, but these objectives are only on the scale of the building to which they apply. Each building is designed independently, drawing from the earth’s resources for its proper functioning: its photovoltaic potential, solar, wind, cooling power, views … (Fig. 38) In order to remain on a high level of efficiency, these objects establish around them a non constructable zone in order to preserve their «area of resources.» While the environmental discourse promotes density and the restricting of the urban tissue, the additional logic of this approach suggests a frightening city, composed of islands-buildings or of bubble-environments. This exclusive position results in one building invisibly pushing the other away. (Fig.39) If everyone has to reach their goal individually, they must defend their borders and literally keep their potential invaders far away: i.e., those who threaten to make them less effective by penetrating their «area of ressources».

Let’s imagine an energy-plus office building – a BEPOSA «BEPOS» is a an Energy-plus building, that produces more energy than it consumes in its operation over the period of one year. – which produces more white energy than it consumes. It is built in a sparsely populated area under redevelopment. Its roof is largely exposed to the sun because it is equipped with large solar panels. Three facades open on to views and its premises benefit from a generous access to daylight. This BEPOS «lives» very happily and successfully until a second BEPOS is built next door. Higher and larger, it encroaches upon the resources of the first. But because the BEPOS was only conceived within its own context, the consequences of future construction were not considered. Now, little BEPOS has its roof in the shadow of the big BEPOS, producing no more energy, while two of its facades no longer have access to views or daylight. From BEPOS, it has become BENEG: «energy-minus building». (Fig.40)

In the urban pact that we imagine, individual buildings are aware of possible inconveniences, that is why they give up their individual interests in order to highlight the collective interest. They forgo the distanciation philosophy to reconnect with the values associated with urban collectivity: proximity and sharing. (Fig. 41) In the above scenario, when the two buildings remained isolated, one of them was necessarily «bad», it suffered from the presence of the second. But if they decide to pool their resources, they can both become «good». Generally, a new development which aims at «energy-plus» is required to have overall positive effects on its environment. If it causes the existing conditions to deteriorate or points out in a Manichean way the weaknesses of its neighbors, it induces negative externalities. It is from the accumulated experience of our firm on projects and situations in which the BEPOS have showed its limitations and its aberrations that the TEGPOS equation was born: a «Positive Global Energy Territory». This reflection on the Positive Global Energy of a building, neighborhood, city or region comes from an integrated and systematic design approach that multiplies the energies to take into account (kinetic energy, creative energy, economic energy, social energy). We believe that to make a city sustainable, it is primarily to create value by maximizing the positive externalities of each project. To achieve this ambition, it is essential to break down barriers between disciplines and to use multidisciplinary approaches. The TEGPOS we have invented can be defined by the following equation:

Energy use + Embodied energy + Kinetic energy + Social Energy + Economic energy + Creative energy + Transformation energy > 0

TEGPOS is an equation that is both critical and virtuous. First, its aim is to go beyond the issue of construction efficiency by asking questions of sustainability at the regional level. Secondly, it proposes to enlarge the definition of energy. Basically defined as a moving force – power or potential – energy is now too often limited to describe energy consumption. The TEGPOS equation incorporates the assertion by Lavoisier: «Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed.» This equation is not mathematical, it is a philosophy, a matrix to think. If the model BEPOS prohibits many things, the TEGPOS allows potentially a multitude. The TEGPOS does not seek to restrict the possibilities, but rather to reopen the funnel of sustainable development: to inspire people to propose, to invent and to innovate. (Fig. 42)

(This article was published in Stream 02 in 2012.)