The potential of the night

- Publish On 28 October 2024

- PCA-STREAM

- 19 minutes

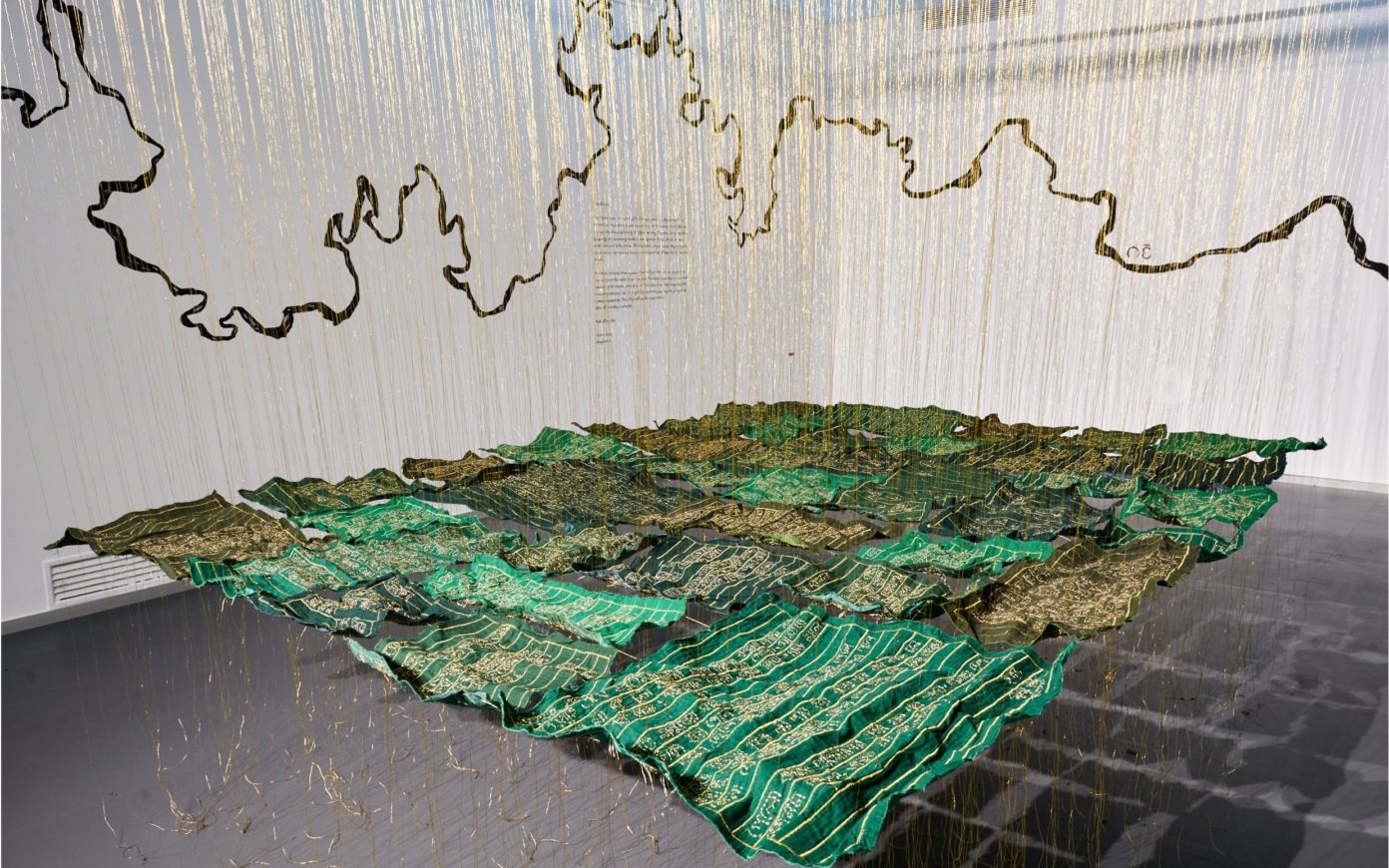

Once a sanctuary for dreams and imagination, nighttime has now been relegated to the mere role of a utilitarian prelude to daytime. Nocturnal realms possess an alchemical power capable of transfiguring our perceptions. However, when viewed through the lens of urban uses, the night also exacerbates inequalities and raises questions about the possibility of achieving an urban night that is accessible to everyone. Exploring the range of possibilities associated with the night reveals it as a space-time where complex interactions are woven that could be revitalized through a chronotopic and inclusive architecture.

To set things in motion and attempt to better grasp the essence of the night, let us take a journey through the nights of history, outlining—through the lens of nocturnal practices—the contours of a night whose perception, and even more so its experience, have evolved over the ages. The Gauls measured time in nights, the Greeks regarded it as a wellspring of wisdom, while the Egyptians attached premonitory value to nocturnal dreams. During the Renaissance, homes were redesigned to open more to the outside, thanks to an urban space made safer both at day and at nightJean-Noël Berguit, “L’histoire de l’homme à travers la nuit” [Human History through the Night], in VST-Vie sociale et traitements, No. 82 (2004), 23–28.. Then followed by a long period when nighttime developed into a space-time for entertainment and alternative expression, as innovations in lighting gradually allowed its taming. But in domesticating the night, have we not narrowed the geographical and semantic dimensions of our nocturnal territories? Should we continue pushing the boundaries of the night, or instead allow it to unfold freely? What does this imply for how we inhabit the nocturnal realms?

“Night, the city’s last frontier”

Tame the night, expand time

Taming the night was long a privilege circumscribed to the private sphere of gardens and palaces, which formed the setting for the nocturnal entertainments of the ruling class, while for the rest of the population, the night was reserved for rest and labor.

The practice of biphasic sleep, uncovered by the American historian Roger EkirchRoger Ekrich, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (New York: W. W. Norton & Company: 2006)., reveals this disparity in practices: up until the Industrial Revolution, peasants and merchants would wake up around midnight after a first period of sleep to carry out of some household chores, look after their animals or simply chat and share an intimate moment before going back to sleep until dawn.

On the contrary, Aristocratic nights were set within vast properties around Paris”Entretien avec Didier Masseau : Fêtes et folies en France à la fin de l’Ancien Régime, XVIII siècle” [Interview with Didier Masseau: Parties and Follies towards the End of the Ancien Régime in 18th-Century France], Histoire Magazine, No. 1. and were a staple of hunting parties and countryside retreats. The court, a veritable mobile city, would drift between the enchanted evenings of VersaillesOne of these grand parties is depicted in Claude-Louis Châtelet’s painting “Illumination du pavillon Belvédère et du Rocher” (1781). —where antique statues, painted scenery, illuminations, masked balls, and fireworks ignited the imagination, fantasies, and transgressions—and rebellious soirées held far from Paris, which also gathered together a rising bourgeoisie, and an aristocracy weary of Versailles. Attending these soirées required long journeys across a predominantly rural landscape, where darkness remained an obstacle.

From the late eighteenth century onwards, the emergence of clubs and coffeehouses, which served as forums for public discussion and debate, gave rise to a new culture of public space, that was primarily bourgeois. Electric lighting further transformed cities. The first incandescent lamps, developed by Edison in 1879, provided brighter and more reliable lighting, facilitating the management of urban space at night. The emergence of nighttime tourism in Paris, which occurred alongside this technological shift, marked a significant transformation in the urban and social life of the capital. In 1834, Prefect Rambuteau proudly announced that the sidewalks of Paris would extend over 29 kilometers. By the end of the century, these pedestrian areas spanned almost 700 hectares, reflecting a considerable effort to create vibrant and active public spaces. This infrastructure allowed Paris to accommodate rapid urban growth and provided a conducive environment for a culture of nighttime entertainment. Residents and visitors embraced this new urban makeup, particularly through the private initiatives of café owners, restaurateurs, event promoters, and other entrepreneurs who created an unprecedented nightlife culture.

This extended period of growth of nightlife businesses and leisure activities fostered the emergence of a working population to support these activities.

Workers: from being invisible to being in the spotlight

In recent years, the trend of night shift work has increased, driven by a society in search of services available around the clock. According to the French national statistics institute, INSEE, in 2022, approximately 18% of workers in the country engaged in nighttime work, up from 15% in 2010 (INSEE, 2022, “Les travailleurs de nuit en France” [Night Workers in France]). However, we cannot overlook the challenges the expansion of this phenomenon presents, both in terms of urban and architectural infrastructure and from a social perspective. Indeed, according to the Observatoire des inégalités [Observatory of Inequalities], night workers are primarily low-skilled malesObservatoire des Inégalités [Observatory of Inequalities], “Les travailleurs de la nuit : surtout des hommes peu qualifiés” [Nighttime Workers are Primarily Low-Skilled Males] (26 March 2024) – http://www.inegalites.fr/Travail-de-nuit., with rates as high as 12% among factory workers.

To enhance the experience and well-being of these workers, public policies and organizational practices must be reevaluated, improving working conditions, providing psychological support, ensuring appropriate compensation, and, above all, recognizing the uniqueness of their contributions to society. It is also crucial to develop services that are tailored to their specific needs, whether that involves healthcare services available at unconventional hours, dedicated infrastructure, or places to go unwind that are accessible outside of standard hours.

Commuting to work is one of the drawbacks of asynchronous work, especially for workers getting by without a car, given the reduced availability of public transport at night. Implementing expanded routes or on-demand transportation services is essential to meet the needs associated with nighttime work. In the city of Le Havre, the “L’iA de Nuit” service operates year-round, from 12:30 AM to 5:00 AM, and until 6:15 AM on Sunday mornings. Reservations can be made online between 24 hours and 30 minutes in advance, and pickups and drop-offs are only at designated LiA de Nuit stopsL’iA de Nuit [public transit brochure] – https://www.transports-lia.fr/ftp/document/flyer-lia-de-nuit-062018.pdf. Access to round-the-clock transportation options often reflects political will rather than technological inability—for example, New York City’s subway operates with three tracks instead of two, allowing maintenance work to be organized without disrupting subway operations.

According to a study by Apur (the Paris Urbanism Agency)APUR, Paris la nuit [Paris at night] (2004). Exploratory study by the City of Paris and the Comité RATP., it appears that Paris has effectively implemented its urban nighttime policy and successfully addressed various nighttime service needs, but it continues to face significant tensions associated with conflicting urban uses due to its high density.

The 24/7 “marketplace” city, a manifestation of consumer society, serving the needs of consumers wishing to find just about anything at any hour of the day or night, which is reflected in the extended opening hours of businesses. The city also offers a diverse range of services, from healthcare to dining and evening education, which are already well integrated into the neighborhoods. These services are still poorly known, however, resulting in a significant loss of potential earnings.

Beyond the challenges of ordinary nightlife, the night is also the stage for unforgettable moments, when the city transforms into a space of magic and emotion. Large-scale events, such as concerts, outdoor performances, and cultural events, magnify the darkness, creating memorable collective experiences. One of the most emblematic examples of this transformation is the city of Paris’s nighttime events policy. As shown during the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, most opening ceremonies have been carefully orchestrated to take place from 7 PM to 11 PM. This choice of scheduling, perfectly timed with the onset of dusk, is no accident. The City of Lights has skillfully staged this transition, asserting its status as a capital of inclusivity and nighttime appeal.

“Time management to save space”

A temporal approach to the city

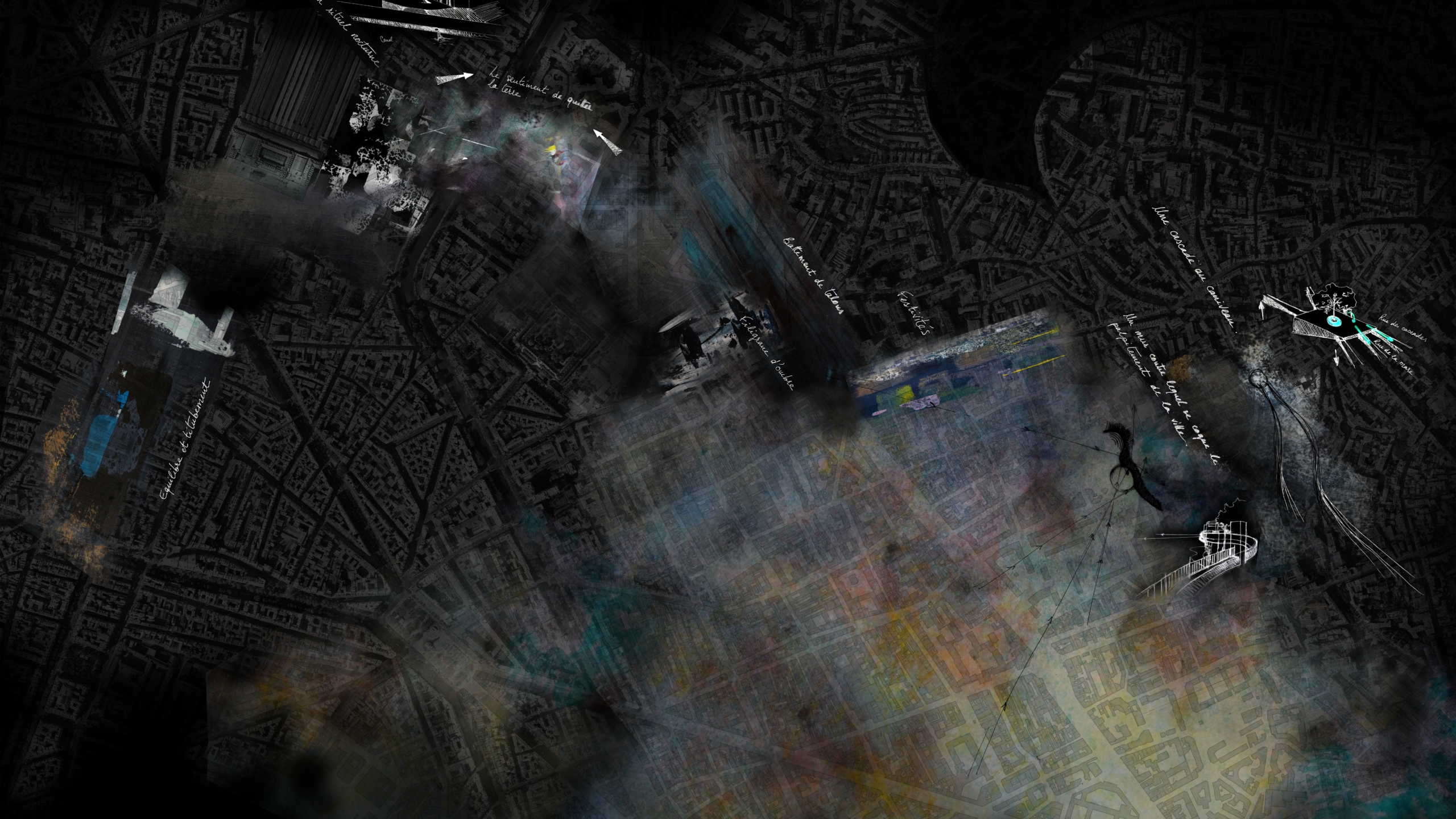

Since the late 1990s and such foundational works as Luc Gwiazdzinski’s La nuit, dernière frontière de la ville [Nighttime, the City’s Last Frontier], we have become aware that adopting time as a key to understanding urban spaces not only highlights the monofunctional organization of cities, but also nuances the concept of the “dense city”—the vertical city that combats urban sprawl by optimizing every plot, interstice, and corner. Indeed, even when urban intensification is carried out thoughtfully—combating soil artificialization, taking care of the existing fabric while adapting it to contemporary challenges, and reintroducing the living—, it cannot be sustainable without considering the differences in temporalities and uses of a given space. Though theoretical concepts, such as Luc Gwiazdzinski’s “time-based urbanism” and the “malleable city,” have flourished and infused architectural thought, chronotopic projects have been slow to become more prevalent.

Indeed, when twilight breaks, the entire city is rewritten in chiaroscuro: the urban masses—office buildings, business districts, corporate headquarters—empty out, while residential neighborhoods and dormitory towns, abandoned during the day, fill up. This urban life cycle, although now well known to all, should be seen not only as a genuine creative opportunity for urban stakeholders but also as one of the approaches for adapting cities to contemporary challenges, not only over the long term but also over the short timespan of the 24-hour day.

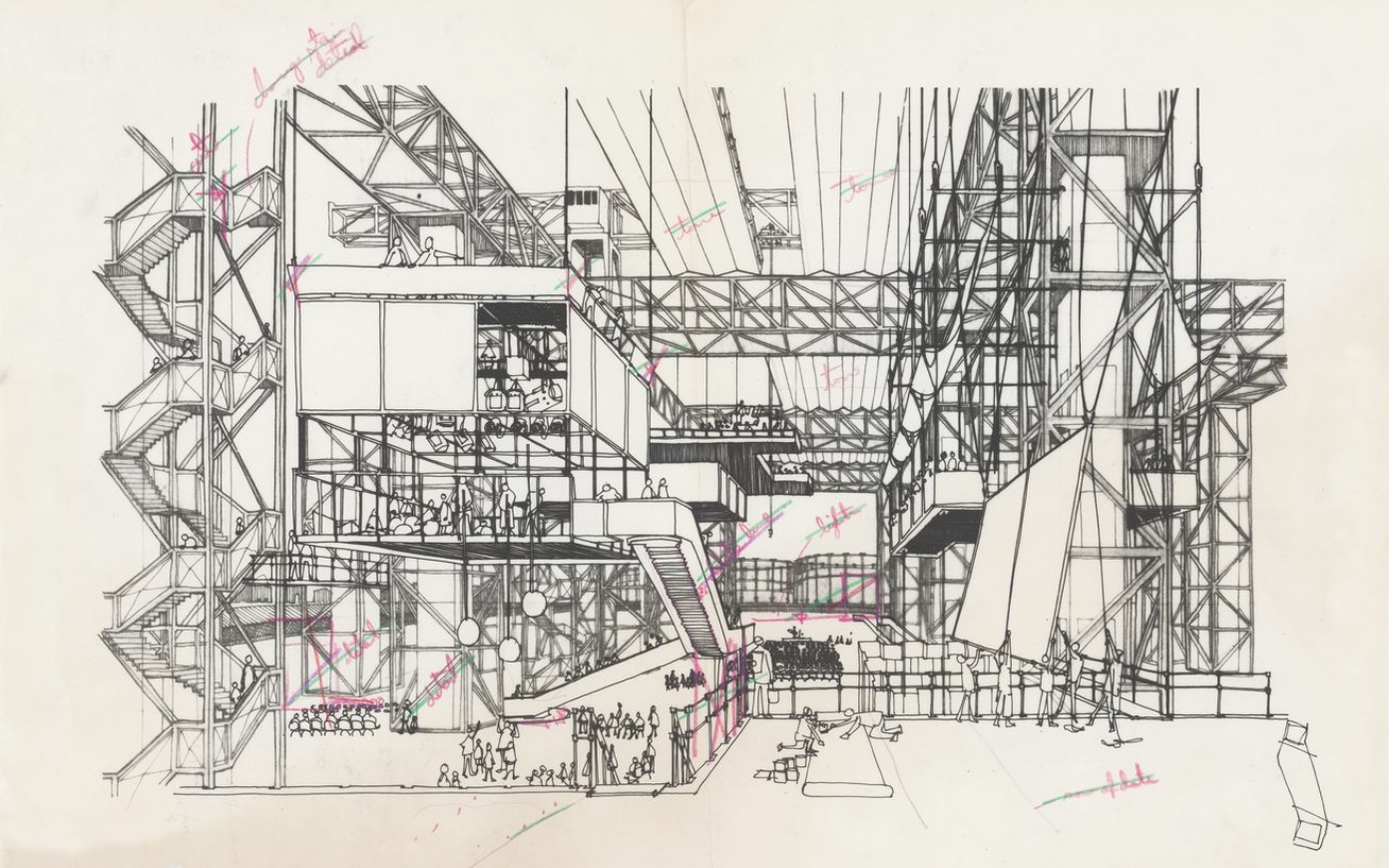

Envisioning the city through a temporal and rhythmic lens inherently places uses and users at the forefront, perhaps even establishing them as fundamental prerequisites for urban development projects. In 1961, Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price imagined the Fun Palace, a “laboratory of fun.” Designed as a flexible framework in which “programmable spaces” could be inserted, the structure of the Fun Palace was intended to change at the request of its users, serving as a pioneering example of modular architecture.

Alongside the plurality of uses is the temporal dimension, understood as an intensification of use that “increases the lifespan of usesFrank Boutté, “Bureaux le jour, logements la nuit : peut-on intensifier les usages du bâti ?” [Offices during the Day, Housing at Night: Can the Utilization of Built Structures be Intensified], Léonard Conference, 6th edition of the Building Beyond Festival.” and allows for the complete transformation of buildings with low temporal intensity into chronotopic buildings. Extending the lifespan of uses could contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of buildings, given certain conditions. Beyond embodied carbon, associated with the materials and construction itself, the operational carbon footprint, which encompasses all emissions released from its ongoing operation, must be sufficiently optimized to explore a strategy of intensifying uses. Furthermore, in addition to the materials used and/or reused, it is important to consider the construction principles that are implemented (such as off-site construction), as well as the architectural form of the building itself, which should ideally be modular and reversible. This methodology, enhanced by consideration of uses—both mixed and chronotopicChronotopia refers to the simultaneous consideration of both temporal (chronos) and spatial (topos) dimensions. It means considering space based on temporality and potential uses, while also considering the demographics that are represented. The concept enables a reimagining of spaces by pooling needs and/or blending uses. Source: https://www.iwms.fr/edito-2023-annee-de-limmeuble-chronotopique/.—therefore takes into account the entire life cycle of the building, from construction to occupancy over time. The fight against the obsolescence of buildings is thus enriched by a twin struggle against the obsolescence of uses.

Work is arguably the one urban use that leaves a market temporal imprint on the city. Indeed, the barring the “city that stays awake”—that of night workers—, entire office spaces, or even entire districts, are abandoned at nightfall. What realm of possibilities then exists for a highly mono-functional area like the La Défense CBD? According to Céline CrestinBureaux le jour, logements la nuit : peut-on intensifier les usages du bâti ?” [Offices during the Day, Housing at Night: Can the Utilization of Built Structures be Intensified], Léonard Conference, 6th edition of the Building Beyond Festival., Director of Strategy and Responsible Development for Paris La Défense, “In La Défense, focusing only on offices, between vacations, nighttime, and weekends, these are hardly used 30% of the time.” Combining uses thus appears as a solution to address this underutilization of available built-up area and thoughtfully intensify cities.

Reversibility, mixity, equality?

However, Mixed uses does not necessarily imply equal access to space, let alone peaceful access. Beyond the debate surrounding the desirability of the “24/7 city,” it seems crucial to inquire about which populations have the least constrained access to the city—that is, an access that is privileged and favored by their social class, societal integration, age, gender, and health status—and more specifically, access to the city at night. Feminist geographer Leslie KernLeslie Kern, “Rethinking Urban Spaces through Gender Mainstreaming”, in Stream, No. 05—New Intelligences (2021). thus explored the differentiated perceptions of the city at night based on gender, developing in particular the concept of “geography of fears.” Indeed, while the sensory experience of the night is, as a matter of fact, altered by the intensification of our perceptions (our sensitivity to noise, light/darkness, and lively/deserted neighborhoods), this is all the more the case for women (and individuals identified as female). This geography of fear takes on a new dimension for individuals experiencing hardship, who are compelled to “inhabit” the night because they cannot dwell elsewhere: their experience thus differs significantly from that of transient nighttime users, regardless of who they are, as it forces immobility in an urban space that is typically only passed through. Accessibility to the night, through the development of chronotopic projects that promote mixed uses, cannot therefore be conceived—nor implemented—without reintroducing the notion of inclusiveness.

In addition to these considerations are the tensions arising from mixed uses, between the “sleeping city” and the “partying city.” Luc Gwiazdzinski suggests that we should “envision the 24-hour city without imposing it on the entire city. The focus could be on ‘oases of continuous time’ offering clusters of public and private services (shops, medical offices, childcare centers…), situated in areas of flow that do not disturb the sleeping city.”

Urban Metabolism: a Theoretical Framework Conducive to the Emergence of Temporal Urban Planning?

The theoretical framework of the urban metabolism allows us to conceive of the city as a complex system, in contrast to the mono-functional city that is conceived and organized in silos—a legacy of modern dualistic thought. The fractal approach developed by PCA-STREAM and described by Léone-Alix MazaudAux racines de la ville métabolisme [At the Roots of “Urban Metabolism”], Léone-Alix Mazaud, Stream Voices, No. 05 (Avril 2022). articulates “circularity in the built environment, which forms a first metabolism nested in a district or an avenue, which is itself embedded in the metabolism of the city, and the cities themselves involve metabolism between one another,” and enables us to capture a city in motion composed of “beating hearts” in constant interaction, at the pace of the inflows and outflows. These material transformations at different time scales punctuate the various metabolisms of the city, associated, for example, with nutrition, mobility, respiration, or the sleep cycleChaire Ville Métabolisme [Chair of Urban Metabolism], Université PSL..

In this perspective, the methodologies for understanding the living city explored by Pauline DetavernierPauline Detavernier, “Explorer les méthodologies de la ville vivante” [Exploring Methodologies to Understand the Living City], Stream Voices, No. 09 (2023).—whole building life cycle analysis, typically calculated over 50 years to consider their average lifespan, and that of the urban metabolism, calculated over one year—could benefit from evaluating a building’s life cycle over the course of 24 hours, thus intertwining analyses across different temporalities. By going beyond the life cycle analysis focused solely on materials and inflows, outflows, and storage, the 24-hour cycle thus allows for the reintroduction of the notion of urban uses and/or land use occupation.

Beyond a cyclical analysis of the flows that allow the urban metabolism to sustain itself, the concept of “urban stacks” understood as sociotechnical systems operating at all urban scales (building—neighborhood—city) seems particularly well suited for thinking about the urban night and how it intersects with the built environment (the emptying buildings), infrastructure (public amenities such as lighting), mobilities (the challenges of accessibility and the networking of public spaces), nighttime uses (by partygoers, activists, sleepers, workers, and the excluded), and the living (both human and non-human). The theoretical framework of the urban metabolism allows for a better understanding of what the night does to the city, but also what the city does to the night, by multiplying the scales and entry points while combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. It is crucial to emphasize that the notion of use, while primarily employed anthropologically in this article, must also be understood more broadly, for and by all living entities, in order to create a truly sustainable, desirable, and inclusive city.

Gianvito Corazza, project assistant in the urban planning department and Lucie Wix, communications at PCA-STREAM