Urban Metabolisms: Combining Complex Approaches

- Publish On 18 November 2017

- Philippe Chiambaretta

Beyond the debates surrounding the Anthropocene—dating it, taking responsibility—the need to combat the disastrous effects of human development on the planet is beyond doubt. Acknowledging that these consequences are specifically incarnated in cities, architect Philippe Chiambaretta points toward a paradigm shift—moving from a mechanical vision of the world to an idea centered on the living—that reactivates the notion of a metabolism. The concept of the living allows us to go beyond the dualism and anthropocentrism introduced by modernity, driving us toward a symbolic and practical idea of the city as an urban metabolism and pointing toward an approach that takes the ecological challenge into account in order to “manage” the city. Flying in the face of the formal pride of the architect, the figure of metabolic planner emerges, able to combine complex visions and approaches, notably by moving beyond the traditional rifts between urban protagonists, working toward an intense diversity of uses, opening up temporal dynamics, and by reintegrating the living.

Modern Exhaustion

Since the fifties, the great demographic acceleration of the human race has been accompanied by a profound transformation of its ways of living: the percentage of humanity living in cities, from 35 percent in 1950, should reach 75 percent in 2050. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Population Division (2014) : “World Urbanization Prospects : Revision”. In one century, we will have gone from 746 million to 6.5 billion people living in cities. Megalopolises concentrate the bulk of the world’s population, extracting natural resources and pumping out waste. We will not be able to stem humanity’s ecological impact if we cannot master the environmental impact of this urban proliferation. Unfortunately, the theoretical and methodological tools available to us for achieving this mastery are only in the embryonic stages of their development.

This new condition—a symptom of the Anthropocene—requires that we free ourselves from three centuries of the founding certainties of Western Modernity, from a relationship with the world defined by the nature/culture, subject/objet, machine/organism dualities. All fields of knowledge are working to counter the consequences of our insolent development, to break down this model that has been built on the central position of man. To move beyond it will require a paradigm shift: from a machinist view of the world, we are moving toward a vision which is centered on the living, one that will allow us to reconsider the idea of the urban metabolism.

The Living as New Paradigm

The first photograph of the Earth taken from Apollo 11 in 1969 revealed the fragility of our planet and its living singularity in the infinite cosmos. This “advent of the World” appeared just before the publication of the Meadows report, that would show the environmental impacts of human activity on the planet from a scientific point of view. The most prolific challenges to modern rationality have emerged from the life sciences. In 1974, Henri Laborit, basing his work on the cognitive sciences, proposed a new biological matrix as a basis for understanding human behavior in social situations. He enhanced Marx and Freud’s analyses of cybernetic thinking by following the assumption that a group’s raison d’être is to assure its own survival. The organism—a structurally closed system, but one which is open in terms of thermodynamics and information—maintains itself via a series of internal regulations and exchanges with its surroundings, with the latter being the basis for its sociability.

With this “dissipative” vision in mind, in 1978 the recipient of the Nobel Prize for chemistry, Ilya Prigogine, and philosopher Isabelle Stengers proposed a “new alliance” between man and the world, challenging classical science that had up until then excluded man from the world that it studied. By shifting from nature likened to an automaton to a world that included man within itself, while also admitting that order and balance can emerge from disorder and flux, led to the idea that chaos could be the source of a new order. This outlined a vision of nature in perpetual evolution and an unprecedented scientific humility in the face of the uncertainty of knowledge.

The idea of a complex reality that requires transdisciplinary knowledge was the subject of a number of rich exchanges between figures coming from differing fields such as Henri Laborit, Michel Rocard, Michel Serres, and Edgar Morin. The last name on this list would make complex thinking the central subject of his masterpiece La Méthode, invoking the notion of “reliance” to characterize the need to reconnect what knowledge had separated, compartmentalized and classified into disciplines or schools of thought. On the contrary he decoded in nature a combination of confrontations, complementarities, competitions, and cooperations that exist in a tight and dynamic synergy. This thinking, which had continued to develop since the nineteen seventies, proved to be of prime relevance with the progressive preeminence of environmental questions. The story of the Anthropocene, that has moved human history closer to geo-history, has forced us to rethink our relationship with nature and redefine man’s place as an integral part of it. The concept itself of nature—an anthropic and Western construction—finds itself at the heart of contemporary questions in philosophy, anthropology, and the sciences.

Bruno Latour sees in the Anthropocene the confirmation of what he has been saying for two decades: “We have never been modern,” and that the subject/object or nature/culture separations have never actually existed. By adopting Lovelock’s Gaïa theory, that views the planet as a living super-organism, he frees himself from the limits of the living and the non-living. The speculative realism movement, born in 2007 with Graham Harman, Timothy Morton, and Quentin Meillassoux, approaches the idea of a world rid of anthropic preeminence with a philosophy of things that considers them equal on an ontological level. Following on from Philippe Descola, the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn explores an anthropology that goes beyond the human, questioning the existence of interspecies communication. Via their environmental philosophy, Catherine and Raphaël Larrère call on us to reconsider technology—so that it will take nature into account—by advocating “the art of handling” and of “making do with,” favoring influence over direction.

This is how the living is building a new paradigm at the heart of contemporary thought. It embodies the figure of a complexity that provides a new scientific and imaginary perspective to define our relationship with a world in which we are an interested participant. This notion engages the principles of metabolism, of the ecosystem, of circular rather than linear processes, and the emergence of a temporal dimension. The question of the limits between humans, animals, plants, and inanimate objects is also present in current affairs. Accepting the idea of one world—of which we are one species among many—means that we must question the right that we have granted ourselves to be the masters and owners of nature. What of animals, rivers, and biodiversity in its broadest sense? It is ultimately the limits of the living as we know them that are challenged by the development of artificial intelligence, by robotics, by transhumanism and biotechnologies. Thus, the living constitutes a prism through which to reconsider our relationship with the world in a general sense, and our urban condition in particular.

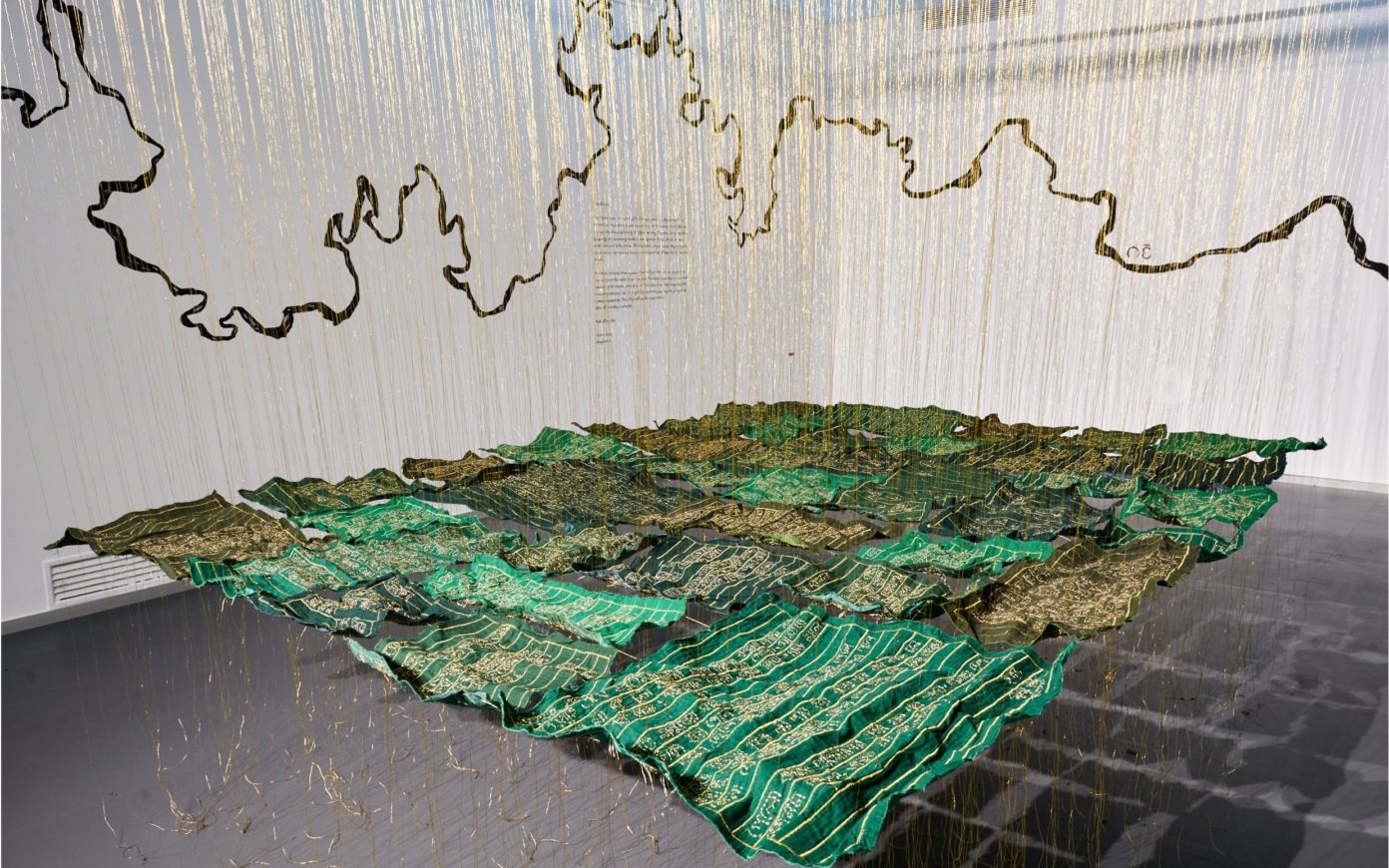

Urban Metabolism: The Figure of the Living as a Means of Moving beyond Metaphor

For centuries, representations of the city have alternated between a machinist vision and an organic one. The metabolic idea implies a process that is specific to the living, of the transformation of a resource into waste in order to extract vital energy. And yet the city emerged from the division of functions between agricultural production, craftsmanship, and business. It manages incoming and outgoing flows and, with the countryside, forms a system of interdependent mechanisms. Emerging from separation, on an ontological level the city is exchanges and flows, and this supports the use of the metabolic metaphor. This synergy between city and countryside lasted until the nineteenth century, but industrialization and agriculture broke progressively with this complementarity. Marx coined the term “metabolic rift” to describe the rupture between humanity and nature brought on by capitalism and the industrialization of agriculture.

The Modern movement encouraged a split from this vision based on the ecosystem, by disconnecting the functions of the city so as to technify its metabolism and optimize its performance. It became a layer of cells to fill, of machines to work, and of flow corridors. This machinist vision triumphed in the wake of the Second World War, accelerating the rupture with the natural world that Marx had criticized, in spite of a few pioneering criticisms of modern technicist rationalism, notably the Japanese Metabolist movement which advocated modular cities that depended on organic growth, or Team X who reimagined accommodation as a system of living clusters rather than a collection of “machines for living.”

The notion of urban metabolism is returning to us now in the context of an imminent ecological crisis, with theoretical and technological tools providing this neologism with new meaning. It now embodies a consideration of the ecological challenge so as to “manage” urban functioning, but also to create a link between the thinking and practices of city developers.

A number of forms of measurement of the urban metabolism have been explored in this way. A first approach, inspired by the sociology of the Chicago school, consists of analyzing the growth and the structure of a city in line with the organization of its flows and mobility. The second, principally quantitative in nature, could be qualified as industrial ecology. It is based on a measurement of the flows of material and energy through the city, in such a way as to be able to manage their environmental impact. The goal is to move from a linear metabolism—which endlessly rejects its “outgoings”—to a circular metabolism that recycles its “outgoings” into “incomings.” A third approach, that of urban political energy, considers the flows not as an autonomous given but as determined by the social and political choices of a city, under the constraints of its needs and the characteristics of its natural and geophysical environment.

The activity of city designers must integrate the whole range of these visions in order to transform the urban metabolism according to a desirable scenario. How can this this concept be translated into a practical tool for development? The figure of a metabolic planner influencing political decisions on different territorial scales is yet to be invented, even though some possible paths are in the process of emerging.

Combining Complex Approaches

The city reimagined from a metabolic point of view hinges on the overthrowing of ideological barriers of modern thought and should be viewed on the scale of the residential unit, the neighborhood, and the city to that of the territory and in fine on a planetary scale. It is a question of working on the transcalar urban metabolism via a group of complex approaches, of producing a city of the living, diverse and changing, integrating and open.

Going beyond rifts

Methods of urban production in Western cultures developed according to a technocratic culture of the rift: separating knowledge and expertise, but also power and participants. They were also founded on a descending logic that moved from the general to the particular: spatial planning preceded the localization of programs, followed by their detailed definition by private operators and then, in the end, their design by prime contractors. Designing a living city requires reestablishing these procedures and practices, moving beyond traditional divides by inviting participants to move outside of their roles and by advocating more open and thoughtful modes of production. The idea is to move from a model which is segmented, descending, and linear toward one which is transversal, ascending, and circular.

With this in mind, new types of project tenders break with the vertical nature of traditional planning, but also with the spectacular formalism specific to architectural competition. Similar to the Réinventer Paris call for innovative urban development projects in 2015, this dynamic comes via a competitive process that places the criteria of innovation on the same level as financial criteria. Putting together multi-disciplinary teams that bring together architects, city planners, landscapers, real estate developers, engineers, start-ups, artists, associations, and researchers turns the logic usually used by participants on its head, and encourages them to move outside of their comfort zones and their certainties, revealing synergies by connecting knowledge and concerns that are usually disassociated.

Linking uses

The living city is first and foremost a diverse one. Modern urban planning has been working to spatially segment our private and working lives, favoring urban spread. Research on the sustainable city enhances density and diversity, in line with the aspirations of new generations. The ubiquity that has been rendered possible by technology favors the decompartmentalization of the times and spaces of our lives between work, leisure, and consumption. Functionalist zoning makes room for a diverse city in which our different conditions of worker, inhabitant, and consumer are reunited on a spatial level.

In buildings that are intended for work, the concept of co-working reveals dynamics that emerge from the informal collaboration between different fields of competence, that the creative industries have theorized under the notion of serendipity. The prefix -co that revisits our practices around the idea of sharing and doing together, is the symbol of this search for synergy. To work in a group is to share ideas, resources, and experiences. The same goes for transportation and housing. The explosion of mono-functional logics and formal mutability allows the emergence of unprecedented and fertile coexistences. The programmatic diversity at the heart of a building that mixes accommodation, workspaces, sports facilities, cultural and commercial spaces, and services ensures an attractive life for various different audiences at all times. This functional complexity and social coexistence becomes all the more fruitful as it opens itself up to the outside world.

Opening up temporal dynamics

A living approach to the city and the fabric of its buildings takes place via an open conception of its temporal dynamics. It is essential to use preparatory strategies to predict the life of a building long before it emerges or reemerges. A project whose program has not been completely set in stone provides spaces for invention through interactions between the future users and inhabitants, who know all too well the services that their space is lacking. By offering the possibility for evolution in the organization of internal spaces, the modular skeleton of a building can then adapt itself to its inhabitants and to the spirit of the times by offering a large amount of freedom in the reversibility of its uses. Fluctuation in the population and the market, the growth of companies, and evolving lifestyles will carve out its anatomy by transforming it over time.

Considered so as to be reversible over the long term, the building has become sufficiently modular to be in a position to provide a large range of uses in the short term, depending on the time of day. A restaurant in an office building can in this way be transformed into an informal workspace, even into a room for projections or presentations outside of its culinary activity. The architecture adapts itself to different times of the city and its users. Time as a component of the living—something that has been overlooked in the approach that has been taken to the city until now—must not become a limit for urban design but rather allow architecture to shape synergies emerging from shared use and the co-ownership of space.

Reintegrating the living

Beyond its establishment in a neighborhood, an architectural project must be founded on the idea of a “planetary garden,” placing man at its core and being responsible for his state. The urban metabolism begins on the scale of the building. A diverse building—which today can be imagined as a wooden structure—can be designed in such a way as to metabolize its waste, transforming it into a resource. Vegetables grown on the roof, on marshland plots fed by runoff water, can be sold or transformed on site according to local distribution networks, and their reused waste could be used to enrich the cultures once it has been composted.

These urban agriculture programs, currently quite fashionable, are still at the experimental stage. No-one knows in the long run whether they will represent concrete solutions for local food supply chains, but they already embody an evolution in the urban fabric’s relationship with nature and the living. In general, the multiplication and new—much larger—scale of the forms of revegetation of structures favor global biodiversity. Landscapers involved in architectural projects now work in collaboration with ecologists so as to explore indigenous species and make choices that are not aesthetic but connected to the richness of the local surroundings.

In this way plant life is integrated into architectural projects very early on. The landscaper no longer intervenes retrospectively in the existing architectural gesture, for the cosmetic purposes of decoration or to hide technical elements. The living occupies a core place within architectural design, defined with and around it, allowing new natural continuities to exist on an urban scale. For the user, this represents a source of comfort, in visual terms, of temperature and of light, but also a relationship with the built that comes via a much wider appeal to the full range of its senses.

Circular, yet open, autonomous yet interdependent, catalysts on interwoven scales, the principles of the urban project should carry an ultimate objective: the improvement of quality of life. Numerous studies point out the benefits of the proximity of a “green space” for the physical and mental health of those living in the city. According to an impact study done in Barcelona, this could prevent over 100 premature deaths each year. Taking these considerations into account, even an office building can be designed as the basis for an open, vital, and natural space. Rather than occupying the spaces of the city, metabolic architecture proposes a hybrid of spatial typologies in order to host new functions while at the same time maintaining urban respiration. Measurements of life expectancy, cognitive functioning, or fertility rates are still in their infancy, but the importance of reconsidering our relationship with urban nature is undeniable.

It is difficult to predict where this metabolic and open vision of the city will lead us, but we should also explore and pay attention to all of the living signals that it is already emitting so as to move from an urban utopia to a concrete creation. Combining complex approaches is a way for us to rid ourselves of our prejudices and ideologies, to accept challenging them, to create the conditions for open possibilities, admitting that the architectural form, all too often primary, remains a dynamic process. This position, one of an architect rendered paradoxically humbler and more attentive through their crucial role at this intersection of fields, gives rise to synergies on the scale of an urban metabolism whose unpredictable character constitutes the most thrilling aspect of contemporary architectural practice.