Urban Psychoanalysis: from Performance to Action

- Publish On 19 November 2017

- collectif ANPU (Agence Nationale de la Psychanalyse Urbaine)

- 11 minutes

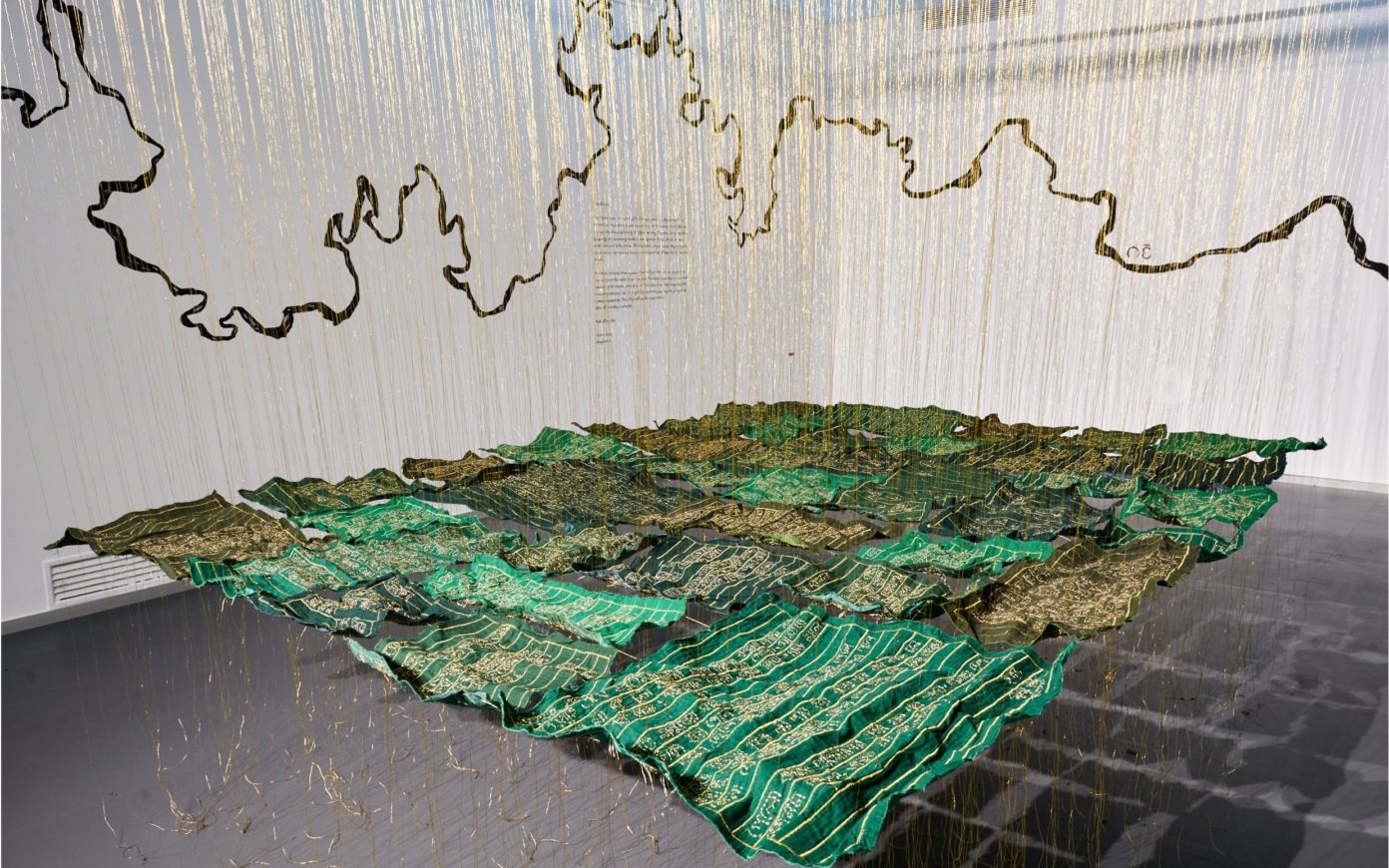

Faced with the acultural approach and functionalist universalization that came in the wake of the sterile smart cities, we have seen the return of work that deals with the imagination and the anchoring to the urban environment. Laurent Petit has initiated a multidisciplinary collective, the Agence Nationale de Psychanalyse Urbaine, adding urban and architectural skills to his practice in order to propose a psychoanalysis of cities. A protocol of restitution of residents’ voices allows the living dynamics of territories to be highlighted, but also to explore the urban imaginations at work, revealing a personality, a rhythm, and also the pathologies of the city. Becoming a participative movement, the agency’s artistic and therapeutic exploration progressively moved beyond simple performance to become a tool for action on the territory. This urban psychoanalysis provides an intimate understanding of the territory and the environment, opening up the possibility for projects of co-construction to participate in the fabrication of the city.

Interview with Laurent Petit, Charles Altorffer, and Fabienne Quéméneur, ANPU (National Agency for Urban Psychoanalysis)

Diagnosing the state of health of the city

Can you tell us about the ANPU?

LP: The project goes backs twenty years ago to a gift from a friend. It originally was a poisoned gift: her husband had given her a Le Corbusier psychoanalyst’s couch to suggest that she be treated. She didn’t take kindly to it. Soon after, the now divorced friend got rid of the couch by giving it to me. Since I was very keen on all kinds of performances at the time, I soon thought of organizing public psychoanalysis sessions for a nominal fee, notably during the Lille Braderie. I remember that passing psychoanalysts would react with anger to this; they would find it hard to understand why we would mock their profession. I then had the idea to hold a show that was called La Finale du championnat de France de psychanalyse [The French Psychoanalysis Championship Finals], with a face-off between a rather whimsical Jungian psychoanalyst and a Lacanian psychoanalyst and inveterate punster. I then started experimenting with the figure of the urban psychoanalyst via some pretty crazy guided tours that were staged during the European Heritage Days for instance.

The agency was created in 2007 following an encounter with Exyzt, which is one of the very first architectural collectives. These architect apprentices were convinced that psychoanalyzing cities could prove relevant. I then asked Fabienne Quéméneur, with whom I had been working for years on another project, to help me put together an agency and reach out to cultural organizations that might be interested in this approach. We then contacted Charles Altorffer to supplement the team with his skills as an architect, a stage director, and a photographer. Since 2008, we have gradually expanded ANPU’s team and psychoanalyzed a little under a hundred cities and urban areas.

CA: When I met with ANPU, there was nothing more than a pitch and a theatric style on the table. The rest still needed to be constructed and invented. I quickly understood that the first step was to teach Laurent the basics of the architectural vocabulary. After the very first rehearsals, I felt that a poetical science was coming into being before my very eyes. Thanks to Pier Schneider, who acted as a matchmaker between ANPU and me, I found myself in the position of a “midwife.” We set out to develop a method that didn’t exist at that point. I sometimes have the impression that we were conducting primary research during these ten years.

FQ: Research, indeed. The confrontation of the contrasting perspectives of two artists, but above all we acted as a team. ANPU isn’t only an “artist” and his “midwife.” Vincent Lorin, Hélène Dattler, Camille Faucherre, Clémence Jost, Dagmar Dudinsky, Lola Duval, Gonzague Lacombe, Maud Le Floch, Laëtitia Sovrano. They all contributed in their own way to the development of this methodology; the poetical science was empirically constructed as a team.

At the confluence between an artistic performance and an urban diagnosis, your protocol consists in “having cities lie down on a couch.” Does that mean that you think of cities as living organisms, endowed with a subconscious mind?

LP: With these ten years of experience, I am starting to feel the condition of cities exactly in the same way as we can feel at a glance the psychic state of someone we meet for the first time. Indeed, cities are living things: they produce beats, rhythmic pulses of their own; they know how to make themselves pretty or they do not; their inhabitants like them or they don’t; they are permeated with happy vibes or are in a situation of extreme stress; cities—and urban areas—send signals that show to what extent they are alive, undergoing great suffering, or half dead. The urban psychoanalyst’s task then consists in having their chakras wide open, with their mind and spirit available to offer themselves to the city that is being analyzed, to offer themselves to this territory in order to understand it and to devise remedies.

Elaborating urban therapy projects

CA: The premise of considering territories as living things helps our correspondents personify the conversation topic. This allows them to relax and to come forward with their affect rather than cling tensely to some technical discourse. It is also a way of pointing out that any city dweller has the right to talk about their city. What we are offering residents is a possibility to reclaim a discipline that has been appropriated by the caste of self-proclaimed ultra-specialists—architects and urban planners—who manipulate language with the sole objective of excluding “non-knowers.” Urban psychoanalysis is ultimately just a poetical science that proposes an alternative, playful framework of interpretation of our urban territories.

FQ: What a bunch of clichés! Pitting caste against caste. We have moved on from that, and using punchlines as shortcuts eventually leads to worthless discussions.

Can you tell us about the urban imagination and the importance of “invisible cities”?

LP: If you are thinking about Italo Calvino’s book when you are referring to invisible cities, then it is fair to say that the urban imagination is very poor in comparison, if not non-existent. People’s imaginary world appears to have withered, probably because society is in crisis and unable to project itself into the future. Probably also because society is afraid it will disappear, but also because it is not in a position to devise some alternative collective project for itself, which may be due to the lack of thorough questioning. If you were to compare the present-day urban imagination with that of the mid-nineteenth century or even of the 1970s, they are like night and day. The residents or experts we get to meet seldom have a flamboyant enough imagination to suggest elaborate therapy projects that could possibly heal local neuroses.

CA: Cities are continuously self-renewing. The urban body is formed by a series of layers. Looking through these layers, shapes that have the potential of revealing a city that no one has thought of suddenly come into sight. That is the subconscious of the city. However, each generation can consciously intervene on its development and I completely disagree with Laurent’s observation. The nostalgia of the 1970s belongs to fifty-year-olds. Each generation carries a creative force within it; only the context changes. I often say that I was born the year Picasso died, that I grew up during the oil crisis, that I went to school with the prospect of unemployment, that I discovered sex as the AIDS epidemic was unfolding, and that television fueled my anxieties. As a typical forty-year-old, I am nevertheless nostalgic of the insane creativity of the 1980s. Context has changed of course, and after these ten years of urban psychoanalysis I find that the good ideas that were given to us—we don’t invent that many—are now materializing, that they are starting to cure cities of certain neuroses.

FQ: The calls we get now are primarily aimed at soliciting ANPU’s assistance on concrete issues regarding the fabrication of the city. We aren’t asked to make speeches anymore but rather to act. I have even started to receive increasingly astonishing proposals, inviting us to bring to the couch topics as diverse as mosquitoes, tires, science, or rising water levels. Little by little, the city has ceased to be our only object of study.

Treatment protocol

Can you tell us what your protocol is for collecting residents’ voices?

LP: In order to collect residents’ voices, we organize “couch operations,” which consist in placing several dozen deckchairs somewhere in the city with a lot of foot traffic, typically on a market day. We use a dozen volunteers to whom we explain our approach and who then don white coats in the livery of ANPU to interview passersby with a Proust Questionnaire of sorts. The respondents are invited to sit in a deckchair for a one-on-one interview where they are asked to compare their city to a fruit or vegetable, to an animal, a movie title, and so on—all in all, a dozen questions that have the effect of unsettling the residents and leading them down the path of poetry, awakening the feeling of fondness and tenderness that we all more or less overtly feel for our city. These questions often become conversations, and the inquiry then ends with the respondents being asked to draw the city. After two hours on site, during which we get to interview between fifty and one hundred people, we bring together the team of volunteers, collect the most interesting answers, and use those to draw up a detailed report.

Another method we use for collecting residents’ voices is through drift with one or more members of the agency, dressed in a white coat. People spontaneously try to know what we are doing there, dressed like that, leading to series of conversations that help us to get a better grasp of the personality of the city through the words of these residents whom we have met completely at random. We also try to work in local cafés, which are often hotspots of urban mythology and remembrance.

Concretely, how do you go about “digesting” this into a functional specification or ordinance? How is this put into practice to cure the “ills of the city?”

LP: The maceration, or digestion period occurring between our in situ investigation and the presentation of our works does not exceed three months. To construe a relevant theory, I mull over my notes, look through our photographic records and the images selected by Charles Altorffer, do some internet searches, and then prepare a mental map of all these elements in order to identify patterns of the city’s personality. I then submit this early analysis to Charles Altorffer, who expands it with his own thoughts on the matter. This is followed by a lengthy exchange between us, eventually leading up to the final diagnosis and recommendations for the residents of the urban territory being analyzed.

We have humble aspirations as far as practical applications are concerned. Urban psychoanalysis is merely an artistic gesture that enables residents to rediscover their territory—and its history—in an unrestrained and fun way. We also try to invite the public to be more forward-thinking and come up with urban therapeutic projects that are inspired by what lies ahead with the depletion of fossil fuels, rising water levels, the collapse of the public service, the end of wage employment, and other joyful prospects that will no doubt finally cause people to change behavior and go back to being resourceful again. For the time being, most of our therapeutic propositions have not resulted in any practical follow-up, simply because our work remains firmly rooted in an artistic bubble that is probably too distant from reality to hope to exert any sort of influence over it. That being said, lately we have been involved in participatory projects that allow us to imagine much more concrete urban projects, thus bringing about significant changes in the way we work.

CA: The key change is that an increasing number of sponsors are asking ANPU to go beyond dramatization. Psychoanalysis is becoming an instrument for direct action on geographical territories. This is why an “executive” division of ANPU is currently being formed: the Atelier Local d’Urbanisme Enchanteur (ALUE, Local Workshop for Enchanting Urbanism). We are shifting toward a cycle of applied research, and I am convinced that our poetical science can contribute something to the making of the city. We have developed many paper-based projects over the past ten years, taking part at our own level in the emergence of new ideas for cities. Our projects of urban cable cars, urban agriculture, urban energy farms, the recycling of highways, densification, and the fight against urban sprawl have wound up in certain contemporary creations. The “artistic bubble” is a sanctuary I am not interested in anymore, partly because it is intended for an audience of insiders. This activity could nevertheless remain within the ANPU; we could create a new department, the Service des Publics Avertis (SPA, Service for Informed Audiences). Finally, to complete the system and really reach the whole target audience, I’d be very much in favor of creating a Fédération de l’Éducation des Élites (FEE, Federation for the Education of the Elites) in order to help policy-makers better understand the artistic endeavors that are grounded in the territory.

FQ: ANPU is undergoing major change, as you have probably understood. The figure of the triangle between the ANPU brand, the ALUE division, and the “la ? (question) sur le divan” [the ? (question) on the couch] division will enable us to get to grips with the world’s future from a number of different perspectives.

Memories of therapy

Among your many urban experiences, both in France and abroad, which ones proved the most memorable?

LP: The extreme situations of cities that are completely messed up, psychically-speaking, such as Marseille, Hénin-Beaumont, Charleroi, Vierzon, and Decazeville particularly stand out. These are endearing cities, with a strong and often dramatic history, but where we always end up uncovering a strong potential for blossoming as well as an urban imagination that is much more present than in healthy cities, which generally seem fairly flat. I have tender feelings, though tinged with dread, for the city of Algiers; we had to plunge into the heart of a Franco-Algerian neurosis that is far from being healed and therefore psychoanalyzed the city with great difficulty. I deeply regret that the feedback conference wasn’t more widely disseminated, which could have contributed to improving things in these highly pathogenic grounds. Much to our regret, we didn’t get to finish the urban psychoanalysis of Beirut in spite of a rather promising start. All these projects take a lot of time to be set up but I hope that one day we will be fortunate enough to get to look into the case of Jerusalem.

CA: I fell in love with Saint-Nazaire and Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône.

FQ: Hénin-Beaumont, I won’t say why.

Residents represent the raw material of your work. Do you see the future as being in the co-elaboration and the co-construction of urban projects, between the public and the private sector, informal and institutional contexts, organizations and individuals?

LP: Residents rarely have the necessary distance to express a relevant opinion on their city. They do little more than repeat the clichés of the media and have an annoying tendency to spout complaints and invectives, as if cities were some kind of self-service that has to meet all the demands of its inhabitants. They generally behave as eternal teenagers that consider the city as some sort of servant that has to cater to their every whim. Thank goodness residents are not the raw material of our work; we would have quickly been caught up the populist wave that is now descending on society.

CA: The stance of the artist that claims to be the custodian of creativity and hyper-poetry through his signature is so last century. The artist of the twenty-first century is an active citizen and not simply an observer or a critic.

FQ: The only question we have to ask ourselves when the phone rings is: “Is the sponsor a willing participant?” We are sometimes contacted because we are in the zeitgeist, because with the “couch operations” we have a brand image that is linked to participatory processes. I therefore have some concerns on whether our sponsor will agree to let go of things and take part in the process without asking us to come up with a new postcard.

LP: In participatory projects, we must succeed in overcoming the first obstacle of the bitterness of citizens and the pervasive mediocrity by deploying a great deal of patience and pedagogy, if only to remove citizens from their individualistic bubbles, which are increasingly tightening up. To do so, a lot of pedagogy and a strong presence in the field are needed, in close cooperation with civil society organizations, which are often hostile to our approach. Parachuting us pseudo-experts on a territory that these organizations know much better than we do is often poorly perceived, especially given that we are often caught between operators that crave results that go down well with the population and an overbearing bureaucracy that is incapable of understanding that such work can only be carried out by improvising with residents. In short, in order to carry out these co-construction projects, it is necessary to be both cunning and generous; we have to become activists and to leave behind our self-appointed role as jesters that has long been the focus of our discipline. These participatory projects will necessarily force the ANPU to undergo profound changes in order to better address the demands that will form the second phase of our project.

CA: After nearly one year of work on the Bienvenue à Babelville [Welcome to Babelville] project, which originated in the 2014 participatory budget of the 11th arrondissement of Paris, I instead found that we inspired good spirits. Partners, residents, civil society organizations, public institutions, and others still feasted on the narrative that we wove from their territory and then gladly received the final marking.

I do not buy into the theory that “people are complete idiots,” without living in cloud-cuckoo land however, because I am well aware of the challenges concerning the notion of participatory democracy. Beyond the pleonasm, we are dealing with a utopia that aspires to devolve power regarding the making of the city to its residents, while at the same time retaining institutional “hyper-control.” In all humility, the ALUE is considering gradually shifting the lines a bit. Urban psychoanalysis must now set an example; otherwise it will remain a new artistic object that will have contributed to the deepening of the divide between the cultural scene, which is isolated in its ivory tower, and the real city.

FQ: We sometimes find it difficult to propel people into the abstract and poetry, but when they do, what a boon! What treasures! Pictures that leave us speechless! Key issues are often raised in a few strokes. When we do the debriefing of the couch operations with our locally-engaged budding psychoanalysts, we often get to enjoy some cheerful moments, with unexpected answers. I sometimes perceive anxieties and mistrust, but I do not sense any kind of bitterness or pervasive mediocrity from citizens.

This article was initially published in Stream 04 – The Paradoxes of the living in November 2017.