Work and Play in Experimental Architecture, 1960-1970

- Publish On 11 January 2017

- Marie-Ange Brayer

Brayer looks at the once frozen, or static, work place as a thing of the past, noting that we are heading towards a more fluid environment. She draws examples from Jacques Tati’s film Playtime, Archigram’s work in displaying the mechanistic qualities of a building; to the work of Walter Pichler creating helmets that become extensions of the brain. She incorporates a myriad of examples to explain the individuals’ ability to absorb his or her space.

Marie-Ange Brayer is doctor in architecture and art history. From 1996 to 2014, she is the director of the Frac Centre.

Throughout the 1960s, as a reaction against the hyperfunctionalism of the post-war years, a radical movement of architects in Europe challenged the values of modernism. An “anti-design” of architecture was proclaimed; notions of form and function were called into question. Architecture as a discipline was contested. These counter-movements took inspiration from certain art forms (arte povera, land art, body art, conceptual art) to form a new liberty of expression. In this context, radical groups challenged the exasperating functionalism of living or working spaces. The hierarchical organisation of work and the demands of productivity have generated standardised work spaces and mono-functionality. Certain scenes from Jacques Tati’s film Playtime illustrate the paragon of the capitalist work space: compartmentalised work spaces reflecting the dehumanization of the worker. The worker is isolated, cut off from a social life, in a frozen time-space. Against this spatial and social formatting of the individual, anti-establishment projects aspired to free the individual from the alienating conditions of life and work. Mobility thus appears as a path towards emancipation. “Mankind will unfix himself,” predicts Ionel Schein, conceptor of the first house made of plastic, in the 1950s; at the same moment, Yona Friedman envisions “spatial cities,” which would be governed by private (as opposed to master) planning of the inhabitants. In Italy, Ugo La Pietra proclaims that one must “inhabit the city.” The architectural experiments of the 1960s and 1970s sought to highlight the liberation of the individual as much in his or her place of work as in their home. At work, the notion of work and the individual appropriation of collective areas were to be substituted.

Constant Nieuwenhuys: the advent of the homo ludens

In 1958, Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920-2005) imagined New Babylon, his first planetary city, in the wake of the Situationist International movement. Nomadism took the place of settlement: architecture dissolves into atmospheric spaces whose intensities are managed by “sectors” on pilotis, covered by ramps and movable platforms, the only architectural objects put in place to welcome the migrants to New Babylon. The sectors function as “atmospheric machinesMark Wigley, Constant’s New Babylon The Hyper-Architecture of Desire, Rotterdam, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art/010 Publishers, 1998.,” transforming architecture into an “artificial environment.” It was no longer enough to produce an architectural form, one had to develop an atmosphere different from the others, to establish a permeability between the outside and the inside, between the dimensions of space and time. According to Constant, architects no longer existed per se: they were now meant to create collectively local “ambiances” in an interactive wayJean-Clarence Lambert (ed), New Babylon. Constant Art et Utopie. Textes situationnistes, Paris, Cercle d’Art, 1997, p. 37.. Systems of sensory stimulation were activated in the sectors according to the activities that were to take place there. Colour, acoustics, lighting, ventilation, temperature and humidity were considered essential elements of the atmospheric modulation of spaces. These were no longer determined by their function, whether for either work or play, but by parameters on a physiological or psychological level, as “transitory micro-environments.” Architecture, as in the work of Yona Friedman, was an infrastructure deprived of forms, on to which activities were to be grafted in a random manner.

“In New Babylon, social space is social spatiality. Space as a psychic dimension (abstract space) cannot be separated from the space of action (concrete space)Jean-Clarence Lambert, op. cit, p. 51..” Social space includes work and art, which are no longer disassociated. It was important for Constant to create a connection between art and life, reviving the revolutionary aspirations of COBRA, which he co-founded with Asger Jorn. For Constant, New Babylon was nothing but a way to see and to transform the world: an “atmospheric machine” that takes the appearance of an architectural project marked by time-space multiplicity. The interpolation of the activities of work and of leisure is at the heart of the mechanism of New Babylon. Since the population is nomadic – therefore in a constant migration – work merges with recreational activities. Contrary to a utilitarian society, “the reduction in the work time necessary for production (resulting from extensive automation) will create a need for leisure, a diversity of behaviourIbid, p. 42..” The “variety of ambiances” would facilitate the movement of the population. “With no timetable to respect, no fixed abode, the human being will of necessity become acquainted with a nomadic life in an artificial environmentIbid, p. 62.” With regard to productivity, Constant opposed the advent of the homo ludens, inspired by the book by Johan HuizingaJohan Huizinga, Homo Ludens. Essai sur la fonction sociale du jeu, Gallimard, Paris, 1938.. “The independence of the work place has an effect on the independence of the habitat, of the living space: the mobility in the space of each person increaseJean-Clarence Lambert, op. cit, p. 52..” Work and leisure fuse together in a concept of “collective creativity.” For Constant, “Man is a potential creator whose creative force is paralysed by a utilitarian social system whose end is automationIbid, p. 26..” The capitalistic alienation of the homo faber (Man the Maker) will end with the arrival of the homo ludens. Constant described architecture and the city through a notion of “networks” in which urbanism and sociology converge in order to outline the contours of a new, non-utilitarian society, based on the creativity of the homo ludens. While social utopias such as Thomas More’s in the sixteenth century enclosed the individual in a work space for the sake of production, New Babylon opened the way to a “creative work” that merged into life itselfIbid, p. 142. Constant, Chant du travail..

New Babylon is therefore a “dynamic labyrinth” that never ceases to change appearance according to the appropriation one gives it. “Life is an endless journey through a world that changes so rapidly that it seems always anotherIbid, p. 64..” New Babylon is a “model” of itself, a building block constantly being redeveloped by its users. New Babylon is the forerunner of our globalised and dematerialised society, a purely informational system. Anchorage in a given space-time has given way to the never-ending traffic of data and of persons, allowing permeability of living and work spaces exactly as foreseen by Constant in the late 1950s.

Archigram / Cedric Price: a society of services

In England, Archigram (1963-1974) drew its inspiration from popular culture, consumer society, comics, fashion, new computer technologies, space exploration and images of science fiction, reflecting a world in transformation. Architecture here exceeds its material dimension in order to project itself beyond its own functionality and to integrate the urban mobility and new technologies. Plug-in City (1964) and Walking City (1964) interpret the city as a “single body.”Marie-Ange Brayer (ed), Architectures expérimentales 1950-2000, Collection du FRAC Centre, Orléans, HYX, 2003 ; Peter Cook, Archigram. A Guide to Archigram 1961-74, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Garden City, 2003, p. 72.

In Instant City (Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton, Peter Cook, 1969), the “instant city” arrives at a given place, infiltrates and creates an event. Instant City then moves elsewhere and gives rise to another ephemeral city. In Instant City, architecture is only an event, an action, a situation. Instant City is one of the first architectural projects of networks: networks of information and of flow, made up of scattered fragments. It is an urban scenario subjected to the permanent rewriting of users who activate it. An aerial city, suspended in air, infiltrated in the existent and the instant, Instant City has no fixed form. The only material that remains is air. In Instant City, the city is made up of projection screens, of tents suspended in the air, of hot air balloons, of technological objects, designed to allow inhabitants to communicate in order to transform the city into a vast interactive “audiovisual” environment. For Archigram, architecture should only be a mobile service, a consumer object: “We are really talking about the possibility that architecture disappears to the point of becoming a daily consumer goodPeter Cook, Experimental Architecture, p. 127..” There is no longer a differentiation between work space and leisure space in Instant City: it is an informational, interactive, factual city.

A house is transformed into an alternative arrangement, sometimes a “garment” (Mike Webb, Cushicle, 1965), sometimes as kit technology as developed by the critic Reyner Banham. The Living-Pod (1966-1967) of David Greene is a cabin-capsule, a nomadic envelope, a liveable car or a prosthetic helmet. Its characteristics highlight its possible activation. Openings in PVC, pipes that criss-cross it, glass-feet providing mobility, all distinguish it as an efficient machine on the verge of coming to life. David Greene carried out his research on a self-sustaining habitat where architecture disappeared into nothing but a service. The Living Pod is an artefact whose hybrid material, made out of everyday objects, looks not to its projection into the future but to its movement into another territory. The Living Pod inhabits at once a physical and psychological body: it is a solitary space-time for work and for leisure, distinguished by mobility.

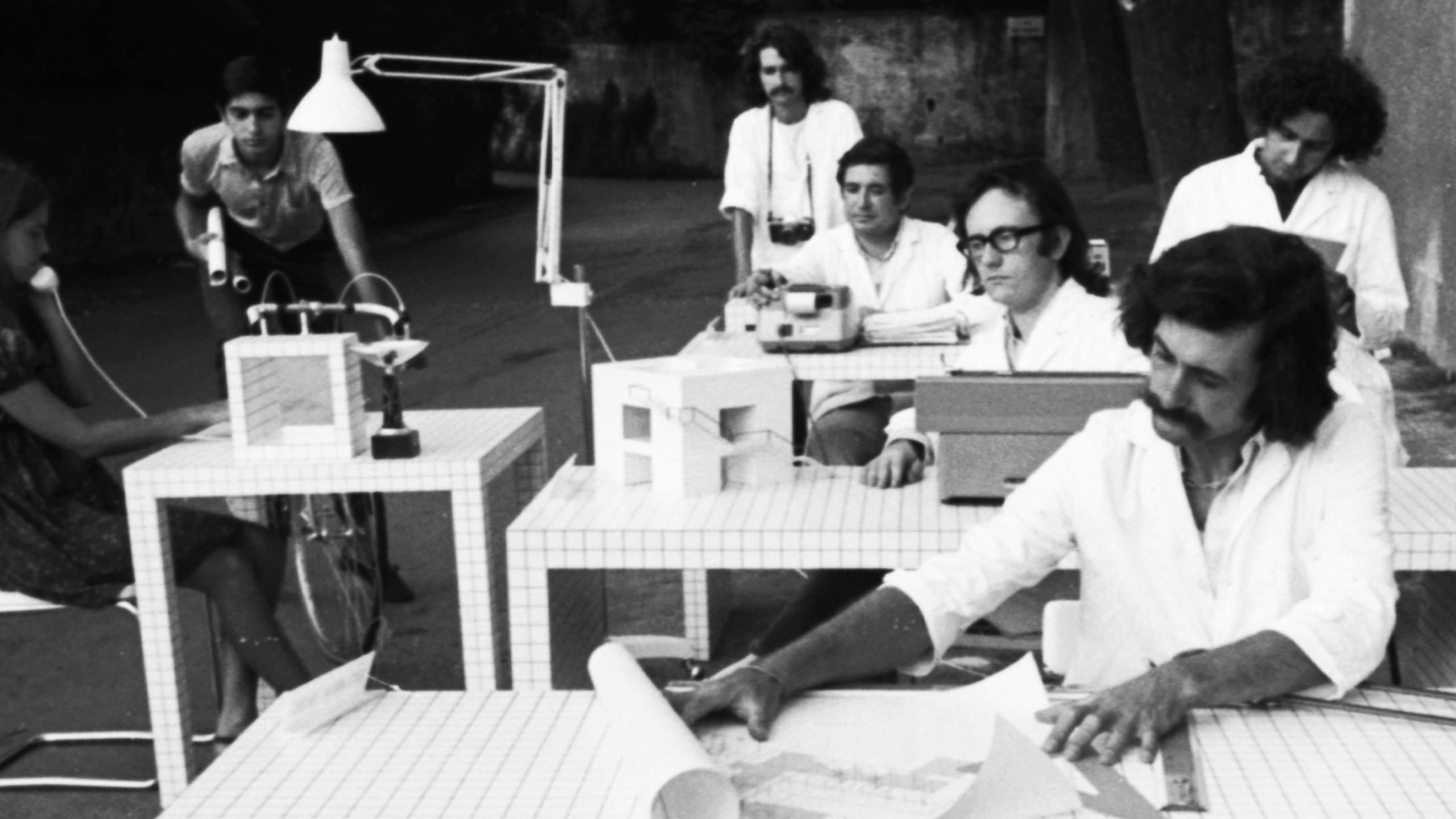

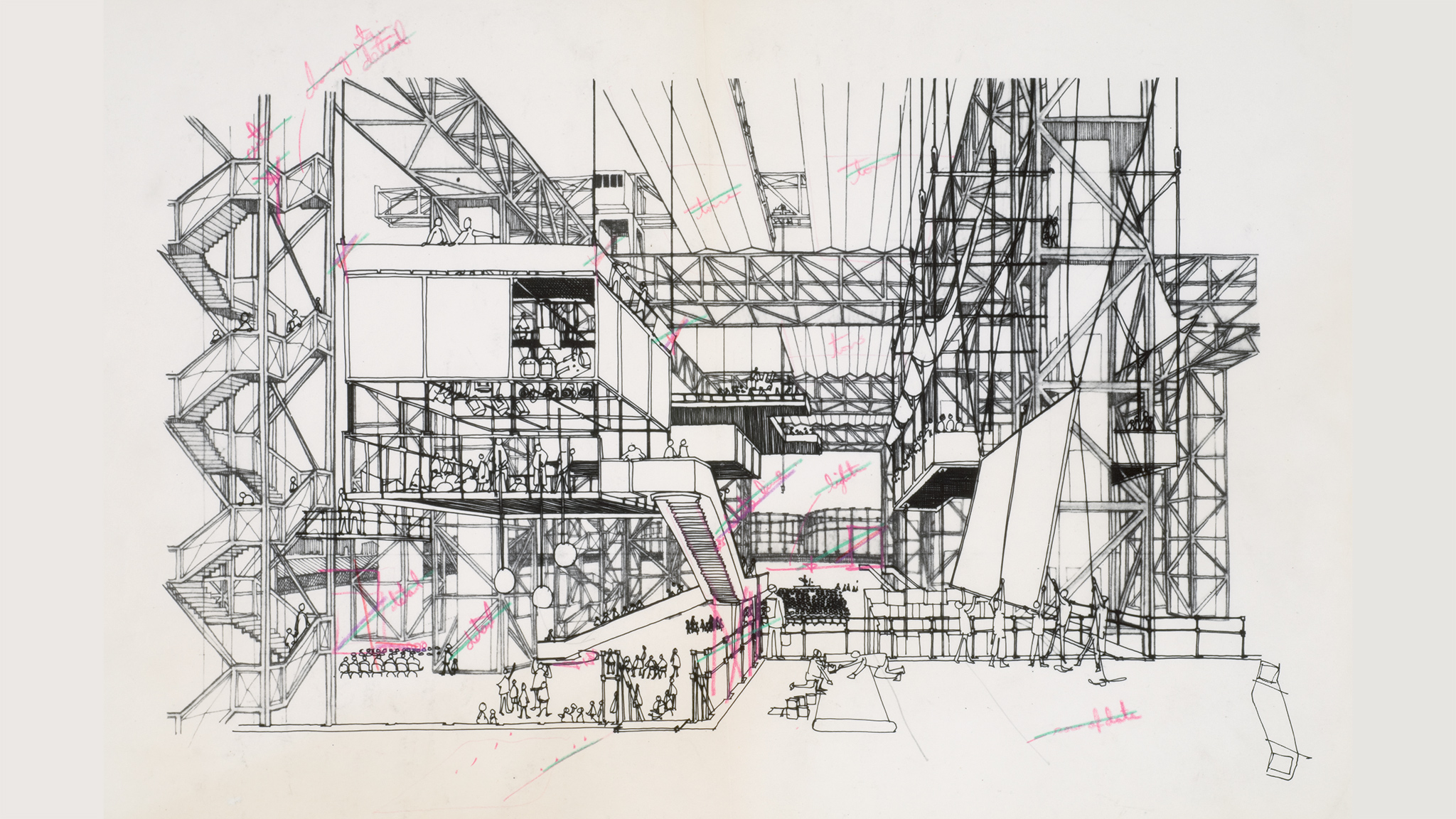

Reyner Banham developed the concept of an architecture in which the residents themselves define their own environment, as in “A House Is Not A HomeReyner Banham, « A Home is not a House », Art in America, New York, II, avril 1965..” In Fun Palace (1961-1964) by the theatre director Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price (1934-2003), users create the architecture. Inspired by theatre, cybernetic theories and information technologies, Fun Palace puts into practice a principle of indeterminationSamantha Hardingham, Cedric Price: Opera, John Wiley & Sons, London, 2003.. Fun Palace is organised from leisure activities at the heart of an infrastructure that is continually reconfiguring itself. Here there are no longer fixed floorboards; the building never has a definite form: instead it is continually being modified depending on the services and activities that the building authorises. One enters by any door and one chooses the desired activity. “When there is no longer any need for the Fun Palace, it will disappearJim Burns, Arthropods: New Design Futures, Praeger Publishers, New York-Washington, 1972, p. 58..” This dimension of permanent adaptability, of direct appropriation of the real, transforms architecture into an environmental device, at once flexible and open, constructing in effect its own demise. “Temporary structures, environments, expositions, inflatables, the object that, if we wish, can be made obsolete after use, will be perhaps replaced by other ‘models’Ibid., p. 43..” Everything renews itself continuously according to desires and needs. The workspace has itself disappeared. The functional space inspired by Taylorism, vertically structured, gives way to a “mechanical layout” of distinct spaces, prismatic and emancipated.

Archizoom: the city as a “residential parking lot”

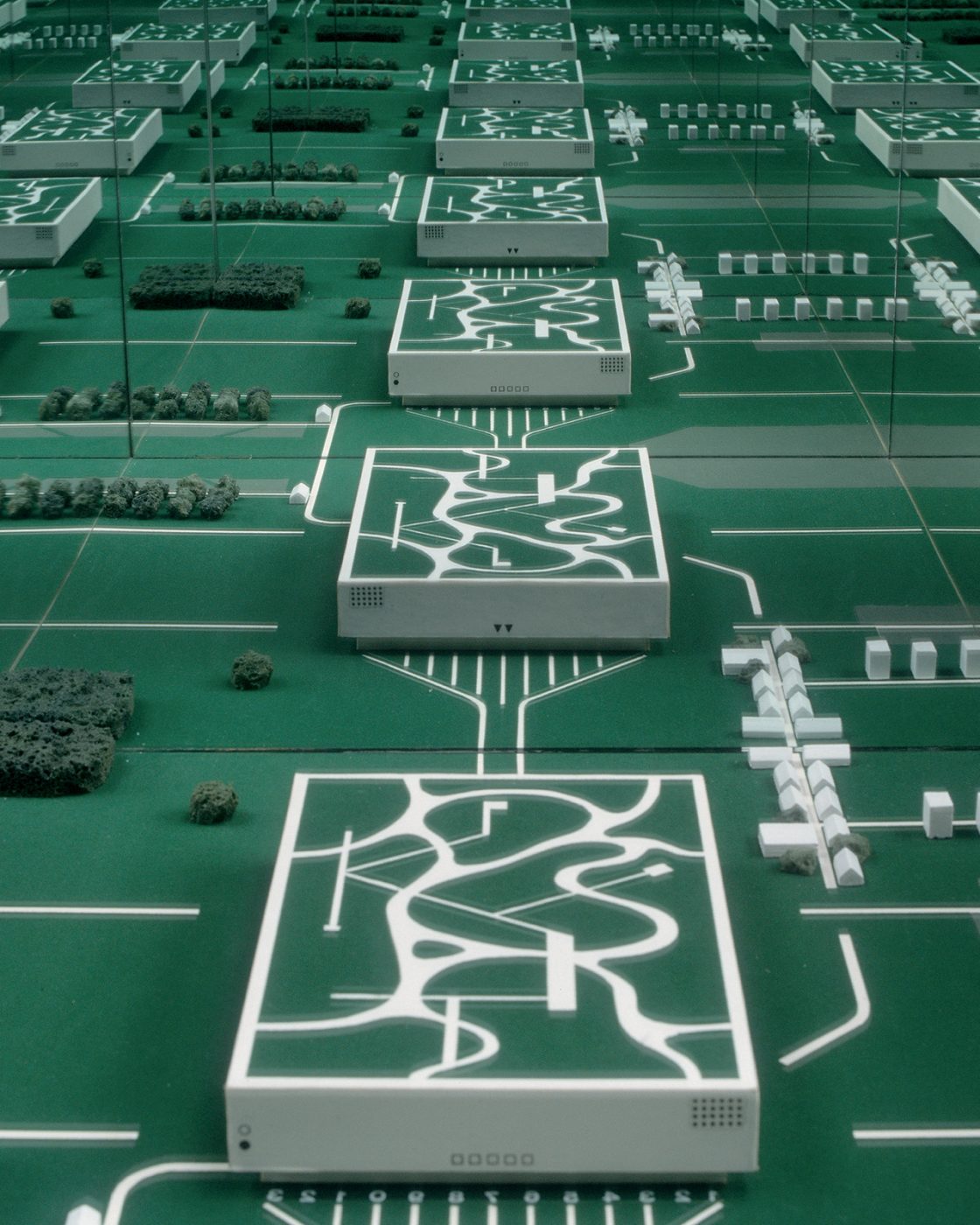

For Archizoom (1966-1974), the content of political vanguards should meet that of the artistic avant-garde. In its beginnings, Archizoom took its inspiration from Pop Art and its criticism of the consumer society to develop an iconoclastic iconography. A modernist credo makes way for a performative attitude to architecture that means the loss of all that is metaphysical and transcendent. Happenings or “guerilla” attacks from now on take the stage. The “project” is without quality, neutral, simply a container. Archizoom swaps the range of values, repudiating its capacity to convey meaning to the project. Architecture is described as “an object of variable use, consumable and perishable, open to all the interpretations possible by the userArchizoom Associati, “No-Stop City. Residential Parkings, Climatic Universal System”, in Domus, March 1971, n. 496, pp. 49-55.. No-Stop City: Residential Car Park, Universal Climatic System (1969-1971) is a “city without architecture” that extends into infinity, an air-conditioned car park or an inhabitable piece of furniture. The city presents the same organisation as a factory or a supermarket, turned into a “vast continuous interior,” “artificially lit and air conditioned.” Work space and living space overlap in the disappearance of all hierarchy between furniture, architecture and the city.

Situated between the “machine for living” of Le Corbusier and the “city without quality” of Ludwig Hilberseimer, architecture has been replaced by an inexpressive, generic urban device, entirely open to collective appropriation through elements of mobile services. The repetitive logic of inhabitable equipment is diffracted in the urban environment. What is meant here is “to liberate one’s own life from workDominique Rouillard, Superarchitecture. Le futur de l’architecture 1950-1970, Paris, Editions de la Villette, 2004, p. 444..” The “houses” are “empty incubators, available for undetermined activities.” The “residential parking lots for metropolitan nomads” are used interchangeably for work, leisure or living. The city has the same organisation as a “large factory or large warehouseIbid, p. 151.” A “inhabitable wardrobe,” a system of combinable elements, serves at once as housing and workplace. “Containers for indifferent use” turn into “equipment for hire.” In the neutral city of No-Stop City, living and workplace are an infrastructure like the others. The generic unity of the container is made up of multi-purpose elements that can be assembled by the user. There is no longer the image of architecture, of representation, since there is a continual transformation of the objects, understood as micro-environments.

At the same time as the communication theories of Marshall McLuhan, Archizoom proclaimed that “media is architecture,” that “information is architecture,” that “behaviour is architecture“Distruzione dell’oggetto”, p. 79..” They called for a “permanent resizing of production space” in the heart of a city “liberated from all ideologyIbid.” Here Archizoom maximises the modernist project and pushes it to its final functional borders. There is no longer any functional zoning, no difference between outside and inside, no opposition between house and work, while the “City” artificially reproduces “the conflict between the ideology of Work and the ideology of Free TimeAndrea Branzi, No-Stop City Archizoom Associati, HYX, Orléans, 2006, p. 170..” Archizoom opposed the notion of work as a “natural human condition” and claimed the loss of the “moral and idealogical structures that accompany work“Distruzione dell’oggetto”, in Argomenti e immagini di design, Milan, March-June 1971, p. 9..” “The abolition of work signifies the taking back of all the creative and intellectual faculties diminished by centuries of frustrated work” that allows from now on the possibility to “go beyond the bourgeois distinction between producer and consumer of culture.” “Each person today self-produces, not only his or her own cultural models of behaviour, but also gains back the right to make his or her own habitat as an immediate and uncontrollable manifestation of the individual personalityIbid, p. 10..”

In A Stop in the City (1968), Ettore Sottsass developed a project on the intermittent occupation of space that blurs the boundaries between living and work space: “On the roof of a building, a place to stop for a few hours, for rest or for work. (…) A rest stop but not named as suchDominique Rouillard, op. cit., p. 450..” Inspired by these experiments, Hitoshi Abe, forty years later in 2004, conceived the project MegaHouse that consisted of inhabiting the city as a giant housePeter Weibel, M-A Brayer, Youniverse, Biennale of Seville, 2006.. The spaces are no longer assigned beforehand but are seen as neutral containers that can serve as an office or an apartment as needed. The city becomes a gigantic unit of services managed by a system called “ZapDoor” that allows the hiring of spaces for a limited time, thus blurring the boundaries of private and public, work and rest, in a fusion between urban nomadism and technologies.

In the 1960s, Andrea Branzi, protagonist of Archizoom, endorsed the dematerialisation of the physical world in an electronic society of services. Architecture disappears as a unitary system or measuring scale from a world now fractured and thus reduced to com-munication networks. The binary relationship of form and function, which served as a foundation in the history of architecture, loses its meaning in the numerical age of the computer, which depends only on its usage, necessarily rhizomatic. Architecture, according to Branzi, can only be “enzymatic”, “weak”, devoid of form. In the video Anomalies construites (2011), the artist Julie Prévieux shows us an empty room filled with computers, lined up in a spatial continuum similar to No-Stop-City. This aseptic space reveals itself to be unable to be situated in the same way as the activities that are meant to take place there but they remain invisible. A voice-over describes the construction of buildings in 3D. Another voice announces: “Everything was so well thought out (…) that one no longer knew that one was working when one was working.” The activity of work is set in its de-realisation, ironically contrasting with the monumental buildings supposedly built by computers. The use seems devoid of any meaning in the loss of work reduced to an activity on the level of a ghostly order in its own “digitalisation.”

Situated between the “machine for living” of Le Corbusier and the “city without quality” of Ludwig Hilberseimer, architecture has been replaced by an inexpressive, generic urban device, entirely open to collective appropriation through elements of mobile services. The repetitive logic of inhabitable equipment is diffracted in the urban environment. What is meant here is “to liberate one’s own life from workDominique Rouillard, Superarchitecture. Le futur de l’architecture 1950-1970, Paris, Editions de la Villette, 2004, p. 444..” The “houses” are “empty incubators, available for undetermined activities.” The “residential parking lots for metropolitan nomads” are used interchangeably for work, leisure or living. The city has the same organisation as a “large factory or large warehouseIbid, p. 151.” A “inhabitable wardrobe,” a system of combinable elements, serves at once as housing and workplace. “Containers for indifferent use” turn into “equipment for hire.” In the neutral city of No-Stop City, living and workplace are an infrastructure like the others. The generic unity of the container is made up of multi-purpose elements that can be assembled by the user. There is no longer the image of architecture, of representation, since there is a continual transformation of the objects, understood as micro-environments.

At the same time as the communication theories of Marshall McLuhan, Archizoom proclaimed that “media is architecture,” that “information is architecture,” that “behaviour is architecture“Distruzione dell’oggetto”, p. 79..” They called for a “permanent resizing of production space” in the heart of a city “liberated from all ideologyIbid.” Here Archizoom maximises the modernist project and pushes it to its final functional borders. There is no longer any functional zoning, no difference between outside and inside, no opposition between house and work, while the “City” artificially reproduces “the conflict between the ideology of Work and the ideology of Free TimeAndrea Branzi, No-Stop City Archizoom Associati, HYX, Orléans, 2006, p. 170..” Archizoom opposed the notion of work as a “natural human condition” and claimed the loss of the “moral and idealogical structures that accompany work“Distruzione dell’oggetto”, in Argomenti e immagini di design, Milan, March-June 1971, p. 9..” “The abolition of work signifies the taking back of all the creative and intellectual faculties diminished by centuries of frustrated work” that allows from now on the possibility to “go beyond the bourgeois distinction between producer and consumer of culture.” “Each person today self-produces, not only his or her own cultural models of behaviour, but also gains back the right to make his or her own habitat as an immediate and uncontrollable manifestation of the individual personalityIbid, p. 10..”

In A Stop in the City (1968), Ettore Sottsass developed a project on the intermittent occupation of space that blurs the boundaries between living and work space: “On the roof of a building, a place to stop for a few hours, for rest or for work. (…) A rest stop but not named as suchDominique Rouillard, op. cit., p. 450..” Inspired by these experiments, Hitoshi Abe, forty years later in 2004, conceived the project MegaHouse that consisted of inhabiting the city as a giant housePeter Weibel, M-A Brayer, Youniverse, Biennale of Seville, 2006.. The spaces are no longer assigned beforehand but are seen as neutral containers that can serve as an office or an apartment as needed. The city becomes a gigantic unit of services managed by a system called “ZapDoor” that allows the hiring of spaces for a limited time, thus blurring the boundaries of private and public, work and rest, in a fusion between urban nomadism and technologies.

In the 1960s, Andrea Branzi, protagonist of Archizoom, endorsed the dematerialisation of the physical world in an electronic society of services. Architecture disappears as a unitary system or measuring scale from a world now fractured and thus reduced to com-munication networks. The binary relationship of form and function, which served as a foundation in the history of architecture, loses its meaning in the numerical age of the computer, which depends only on its usage, necessarily rhizomatic. Architecture, according to Branzi, can only be “enzymatic”, “weak”, devoid of form. In the video Anomalies construites (2011), the artist Julie Prévieux shows us an empty room filled with computers, lined up in a spatial continuum similar to No-Stop-City. This aseptic space reveals itself to be unable to be situated in the same way as the activities that are meant to take place there but they remain invisible. A voice-over describes the construction of buildings in 3D. Another voice announces: “Everything was so well thought out (…) that one no longer knew that one was working when one was working.” The activity of work is set in its de-realisation, ironically contrasting with the monumental buildings supposedly built by computers. The use seems devoid of any meaning in the loss of work reduced to an activity on the level of a ghostly order in its own “digitalisation.”

Superstudio: live and work in “supersurface”

The architects from the group Superstudio (1966-1978) created the Continuous Monument in 1969, an “architectural model of total urbanisation” in which an uninterrupted grid covers the earth. The grid covers everything – land, architecture, city. Superstudio pushes to an extreme end the notion of architecture as projection. The tridimensionality of architecture is replaced by the notion of “supersurfaceSuperstudio, « Supersuperficie », Casabella, XXXVI, n° 366, Milan, juin 1972..” This “reduction of the architectonic object” bears witness to a declared will of the “destruction of the object” for the profit of life, of creative behaviour. The projected models gave way to the “model of a mental attitudeSuperstudio, Storie con figure 1966-1973, sous la dir. d’Adolfo Natalini, Galleria Vera Biondi, Florence, 1979, p. 46..” For Superstudio, radical architecture didn’t mean the production of new forms but rather a way of “integral existence, a superlative means of knowledge and of appropriation of reality.” In this context, the project had multiple facets: installations, furniture, writings, drawings, direct experimentation, behaviour, all seen as “instruments for the re-appropriation of the environment and of the self Adolfo Natalini, Superstudio-The Middelburg Lectures, Design Museum, Middelburg, Valentijn Byvanck (ed), 2005, p. 41..”

Situated between the “machine for living” of Le Corbusier and the “city without quality” of Ludwig Hilberseimer, architecture has been replaced by an inexpressive, generic urban device, entirely open to collective appropriation through elements of mobile services. The repetitive logic of inhabitable equipment is diffracted in the urban environment. What is meant here is “to liberate one’s own life from workDominique Rouillard, Superarchitecture. Le futur de l’architecture 1950-1970, Paris, Editions de la Villette, 2004, p. 444..” The “houses” are “empty incubators, available for undetermined activities.” The “residential parking lots for metropolitan nomads” are used interchangeably for work, leisure or living. The city has the same organisation as a “large factory or large warehouseIbid, p. 151.” A “inhabitable wardrobe,” a system of combinable elements, serves at once as housing and workplace. “Containers for indifferent use” turn into “equipment for hire.” In the neutral city of No-Stop City, living and workplace are an infrastructure like the others. The generic unity of the container is made up of multi-purpose elements that can be assembled by the user. There is no longer the image of architecture, of representation, since there is a continual transformation of the objects, understood as micro-environments.

At the same time as the communication theories of Marshall McLuhan, Archizoom proclaimed that “media is architecture,” that “information is architecture,” that “behaviour is architecture“Distruzione dell’oggetto”, p. 79..” They called for a “permanent resizing of production space” in the heart of a city “liberated from all ideologyIbid.” Here Archizoom maximises the modernist project and pushes it to its final functional borders. There is no longer any functional zoning, no difference between outside and inside, no opposition between house and work, while the “City” artificially reproduces “the conflict between the ideology of Work and the ideology of Free TimeAndrea Branzi, No-Stop City Archizoom Associati, HYX, Orléans, 2006, p. 170..” Archizoom opposed the notion of work as a “natural human condition” and claimed the loss of the “moral and idealogical structures that accompany work“Distruzione dell’oggetto”, in Argomenti e immagini di design, Milan, March-June 1971, p. 9..” “The abolition of work signifies the taking back of all the creative and intellectual faculties diminished by centuries of frustrated work” that allows from now on the possibility to “go beyond the bourgeois distinction between producer and consumer of culture.” “Each person today self-produces, not only his or her own cultural models of behaviour, but also gains back the right to make his or her own habitat as an immediate and uncontrollable manifestation of the individual personalityIbid, p. 10..”

In A Stop in the City (1968), Ettore Sottsass developed a project on the intermittent occupation of space that blurs the boundaries between living and work space: “On the roof of a building, a place to stop for a few hours, for rest or for work. (…) A rest stop but not named as suchDominique Rouillard, op. cit., p. 450..” Inspired by these experiments, Hitoshi Abe, forty years later in 2004, conceived the project MegaHouse that consisted of inhabiting the city as a giant housePeter Weibel, M-A Brayer, Youniverse, Biennale of Seville, 2006.. The spaces are no longer assigned beforehand but are seen as neutral containers that can serve as an office or an apartment as needed. The city becomes a gigantic unit of services managed by a system called “ZapDoor” that allows the hiring of spaces for a limited time, thus blurring the boundaries of private and public, work and rest, in a fusion between urban nomadism and technologies.

In the 1960s, Andrea Branzi, protagonist of Archizoom, endorsed the dematerialisation of the physical world in an electronic society of services. Architecture disappears as a unitary system or measuring scale from a world now fractured and thus reduced to com-munication networks. The binary relationship of form and function, which served as a foundation in the history of architecture, loses its meaning in the numerical age of the computer, which depends only on its usage, necessarily rhizomatic. Architecture, according to Branzi, can only be “enzymatic”, “weak”, devoid of form. In the video Anomalies construites (2011), the artist Julie Prévieux shows us an empty room filled with computers, lined up in a spatial continuum similar to No-Stop-City. This aseptic space reveals itself to be unable to be situated in the same way as the activities that are meant to take place there but they remain invisible. A voice-over describes the construction of buildings in 3D. Another voice announces: “Everything was so well thought out (…) that one no longer knew that one was working when one was working.” The activity of work is set in its de-realisation, ironically contrasting with the monumental buildings supposedly built by computers. The use seems devoid of any meaning in the loss of work reduced to an activity on the level of a ghostly order in its own “digitalisation.”

Hans Hollein/ Walter Pichler: the transformation of space by psychism

Work space becomes the object of recreational experiments from the body – a body wholly physical and psychological – as in the performances of the inflatables by Coop Himmelb(l)au or by Haus-Rucker-co in Vienna. Hans Hollein created Mobile Office in 1969, an inflatable cylindrical structure. Here we find Hollein seated on the grass in the middle of nowhere, working in a minimal space, seated at his “desk.” He could be anywhere, in a structure that is transportable at any moment depending on his activity. The inflatable architecture submerges him completely in his environment. He is neither on the inside nor the outside. In the video of Mobile Office, the telephone rings and Hollein responds, proposing a house with a peaked roof to a client! This installation, which puts into practice the notion of deterritorialisation, takes into account the new modes of behaviour. The mobility of the technological tools of communication has transformed architecture into a portable micro-environment. Work space has no fixed place nor form: it depends only on its occupant and the activities that take place there. With Architectural Spray, Hollein suggested to transform the atmosphere of one’s office if it is not suitable! In Work and Behaviour (1972) or Mantransform (1974-1976), the functionality of architecture has disappeared to leave space for individual action exerted on space-time that has become malleable. Ugo La Pietra also created a transparent bubble that serves as an office in Uomosfera (1968), joining bubbles in a free airy column, freed from any anchorage.

The artist Walter Pichler, who worked with Hollein, invented helmets, prosthetic extensions of the brain, technological organs, allowing one to work or to rest in the same unity of space, at once physical and mental. It is the body that is like a mobile micro-structure bringing together work and rest. There is no other form of exteriority. In Intensive Box (1967), the individual occupies a mobile spatial unit in an inflatable structure. The TV Helmet (1972) confines the individual in a portable living room. The head inhabits the helmet in a metonymic way, as the body does with architecture. Each individual transports with him or herself their own living space. According to Coop Himmelb(l)au, “Our architecture does not have a physical plan, but rather a psychic plan. There are no longer any walls.” In the same way, Haus-Rucker-co’s Leisure Time-Explosion/ Pneumacosm (1969), which plug inflatable cells on to existing buildings, can be defined as a “new urban structure combining units of work and of living, with special spaces for pleasure and relaxationDominique Rouillard, op. cit., p. 221. See also Peter Sloterdijk, Ecumes. Sphères III, Paris, Maren Sell Editeurs, 2005.” The organic space of the bubble, insular and in constant reconfiguration, englobes the activities in a single unit of space-time. This nomadism of the work space, devoid of architectural limits, goes together with an individualisation of space and a loss of anchorage of the subject.

These architectural avant-garde, laden with utopias, incorporate in the heart of their projects the emancipation of the individual through his or her living space. The boundary private-public became non-operational and was replaced by a playful appropriation of space in which one can work and play in the same space. The game and its principal of indetermination, like in the work of Cedric Price, replaces itself in a forceful dimension of work. In the same way that “everything is architecture,” according to Hans Hollein in 1963, everything is from now on a space of play. Whether through the quest for a conjunction between spatiality and social space as seen in Constant’s work; the placing of generic schemes of the production of activities randomly linked to work or to leisure in the case of the radical architectural movement in Italy; or the performativity of the individual in the heart of his or her own environment as in the work of the Austrians: work and leisure are no longer disjointed but give themselves over as the same “spatial object, generator of experiences” (A. Natalini, Superstudio), beyond all functionalism. All of these radical experiments foresee the advent of a society of networks – nomadic and global – where it is no longer the place that is important but the action and the information that is produced. Architecture integrated its randomness while its spatial and social limits were broken down. Work space was transformed into an indefinable, immaterial space, producing forms at once ghostly and informational.

Translated from French by Orhan Memed

(This article was published in Stream 02 in 2012.)