Humanless Art

- Publish On 18 November 2017

- Thomas Schlesser

- 8 minutes

Though contemporary philosophy, faced with global issues, strives to rethink and decenter man’s place in the world—which has been dominant in modern thinking—art historian Thomas Schlesser brings nuance to the common idea of a strictly anthropocentric relationship between man and the world, visible in artistic creation since the Renaissance. Identifying major moments of rupture at the root of anthropocritical visions in the history of art, he sees within them an expression of a form of leveling out of the importance of mankind on the scale of the living. Human fragility thus constitutes both an artistic motif and cause, particularly within popular culture. By analyzing a “cosmic dilution” of the human figure at the heart of historical avant-gardes and of abstractions, through to the performance and Land Art movements, Schlesser reveals an art racked by the disappearance of the human. Without claiming that art has mainly become a “universe without man,” he opens us up to the idea that the most interesting artists are those who intuitively propose “alter-egocentric” visions of the world.

Humankind against nature

In your book, the use of art as an interpretive lens enables you to dispel, or at least to qualify, the mainstream understanding of humankind’s anthropocentric relationship with the world since the Renaissance. What was the starting point of this research?

The starting point goes back to Pierre Huyghe’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 2013, which was recommended to me by my friend Judicaël Lavrador. In an interview, HuygheSee his interview with Philippe Chiambaretta and Éric Troncy in Stream 03: Inhabiting the Anthropocene (Paris: PCA Editions, 2013) declared that his readings of Bruno Latour and Quentin Meillassoux—who endeavors to imagine a “world without humans”—didn’t only interest him but also confirmed his intuitions. I was particularly intrigued by this and, almost at the same time, rereading the part of Baudelaire’s Salon de 1859 where he talks about “the universe without man” and “nature without man,” ten years after my Ph.D. dissertation, something was triggered in my mind. I then decided to trace the genealogy of this idea or, more accurately, of the representations that artists form of it.

You identify three “moments” or “tragedies” that would historically explain the emergence of the great modern movements. How are these disruptions expressed in artistic terms?

In 1755, an earthquake devastated Lisbon and claimed several tens of thousands of victims over the course of two days. There were two conflicting interpretations of this horrible event: on one side, the conventional providentialist reading of the event, held by the Church, speaks of divine retribution which is beneficial to men; on the other side, a rational and enlightened vision, held by Voltaire and Kant for instance, laments a tragedy that stems from a contingency and states that nature isn’t moved by God’s spirit to punish men, but rather is an impersonal force that is indifferent to their fate. During the rest of the eighteenth century, a great number of major disasters occurred, giving rise to an eschatology that could be described as materialistic—in Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, in The Last Man by Mary Shelley, or in the writings of Saint-Simon among other examples. There looms a modern terror: that of an end to the human species that would arise independently from the end of space itself. Gone is the coincidence of the passing of mankind and the dissipation of history: the man could be gone and yet, history would carry on. What I make clear in the first part of my book is that, at the same time as this “anthropocritic” vision, there is also a promotion of annex spheres—animals, plants, and even “things,” if we consider for example the Barbizon school, Rosa Bonheur, Victor Hugo, or Jules Michelet—that also participates in the leveling of humankind’s place in the living world.

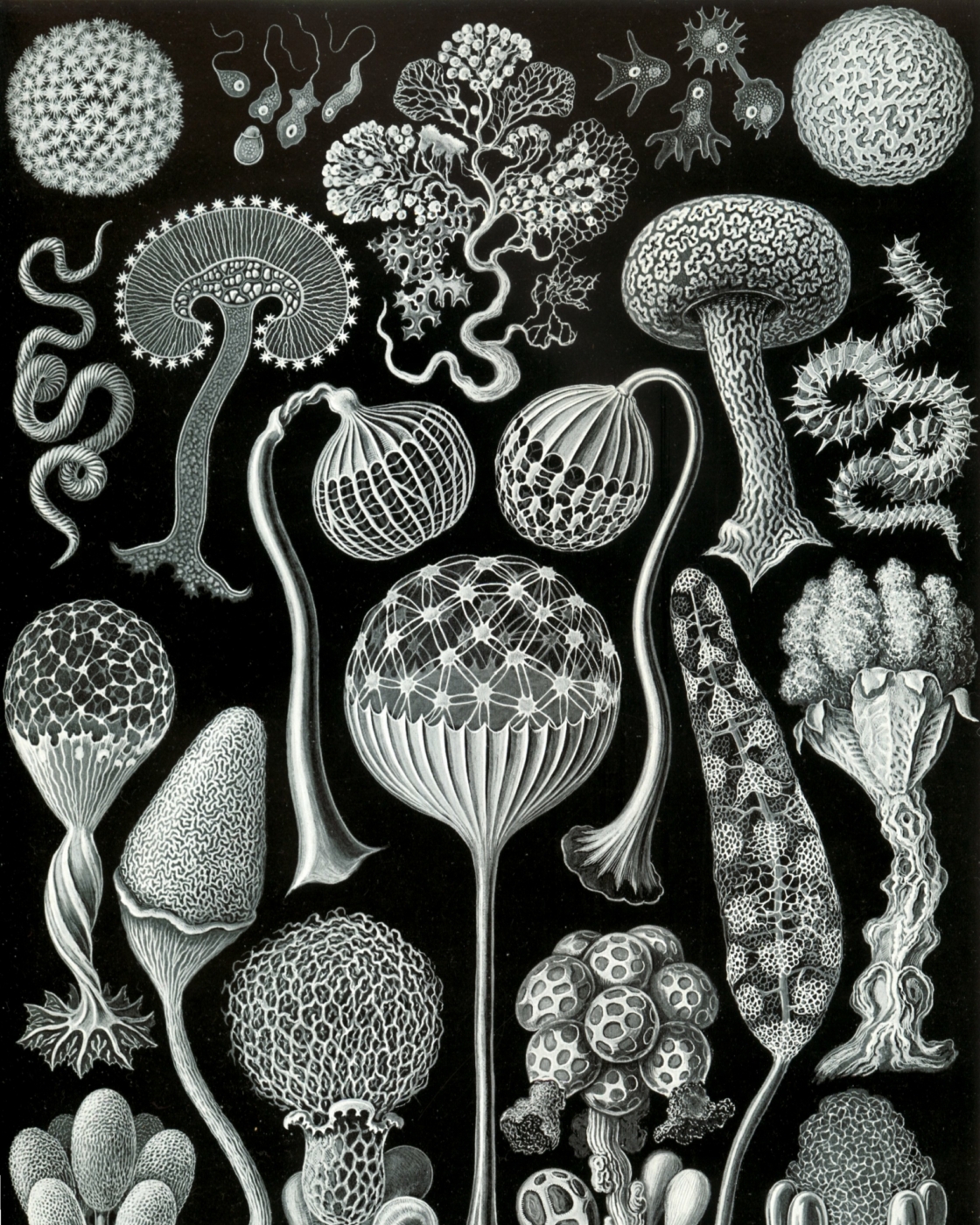

In 1860, then appeared the mental shortcut that designates man as descended from the ape, following the eminently outrageous success of Darwin’s Origin of Species. The narcissistic wound regarding the origins of man conclusively demolishes the fixed and unshakable representation of humankind, thereby reduced to an inconstant and temporary instance. I think we must consider the aesthetics of hybridization and the biological, physical, and mechanical speculations of symbolism or futurism as amplifications—either concerned or exalted—that are permeated with this new paradigm.

In August 1945 comes another moment of shock. Einstein himself declared that atomic weaponry “threaten[s] the continued existence of mankind.” Artists will produce many visual, literary, cinematic expressions of this potential eradication, and often very disturbing ones—I am thinking in particular of On the Beach, Nevil Shute’s excellent 1959 novel. The fragility of humankind becomes not only a motif but I would also say an artistic cause. And the problem isn’t nature’s random violence against man anymore but the chain of uncertain consequences stemming from the telluric action of humankind against nature, which is now the one that suffers. Hence a fascinating and stimulating paradox for the artists of the contemporary art scene: “The chasm of the Anthropocene, where anthropocentrism, which had just reached its full vigor, peaks precisely at that cut-off point after which the Apocalypse takes place.”

Art as a representation of the universe

You mention a “cosmic dilution” to express the dissolution of the human figure from symbolism to surrealism and all the way up to the emergence of the figure of the robot. How could the renewed relationship to the living and to the scale of things direct humankind toward abstraction?

I must first make a very obvious point: there is not one abstraction but, artistically speaking, several abstractions, which both experience a different intensity in the disqualification of the figure and that borrow from very different technical and theoretical avenues. From the point when the essential seemed beyond the reach of human perception—we are allowed neither the access to the infinitesimal structures of reality, nor the access to its most stunning cosmic deployments—painting engaged in another longing altogether: to plunge into the invisible and make the scales of our representations of the universe waver. The illusion of human centrality suffers a double knockout: not only is the human figure expelled but the forms that act as a surrogate on the canvas remind humans that their perception is terribly limited. Things are getting more complicated, however. Many painters have been inspired by this break with human scales to have the ambition both to relate their inner life and to support the creation of a “new man” through the use of abstraction. In short, one form of anthropocentrism is replaced by another; hence Motherwell’s quip regarding the “humanism of abstraction” during a famous lecture that he gave.

We obviously cannot elude the adventures of abstraction when we study the genealogies of the concept of the “universe without man.” But I found most artists to be fairly shy deep down as if a majority of them were afraid of going too far. I think that for artists such as Malevich, Fontana, Klein, and many others, abstraction should rather be thought of as an emancipating airlock of the human condition. This condition—our condition—is one of gravity. The physical gravity that nails us to the ground, but also the moral gravity in the face of our mortal destiny. For these three artists at least, abstraction has the explicit—and, obviously, completely fantasized—ambition to tear the spectators experiencing the artwork away from these two gravities, to elevate the mind and the body, and to make them levitate beyond the contingencies of humanity in a sort of cosmic dilution of being. I remember a passage written by the art historian Kenneth Clark in his classic essay, The Nude, Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form (New York: Pantheon, 1956) where he discusses Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. He proceeds to briefly comment on the levitation of Venus and then expands on the allegorical figures on the left of the painting that represent the winds. In these divine ascensions, these corporal assumptions, Kenneth Clark is already seeing signs of the expression of a powerful emancipation beyond the human condition. I personally see a meaningful continuity between Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Malevich’s Suprematist Painting: Aeroplane Flying.

Can you say a word about the abstract painting that is used as a cover for your book, an artwork painted by Hans Hartung in 1986 that is held in the Foundation you run?

I have no hesitation in saying that T1986-E16 is one of the most exceptional artworks of the second half of the twentieth century. It was painted by Hans Hartung at the end of his life and features an airbrushed blue background, a projection of uneven accumulations of grayish painting rendered with a Tyrolean flicker gun, and much darker tones that give an illusion of relief that is almost satellite-like. In addition, there are a few traces, including some erasures in the upper part of the canvas, where we can discern the passage of a sort of brush or sponge. Though the artwork itself is very simple, it has many aspects to it. This makes it both obvious and complex. It has the crude and mineral aspect of distantly archaic things and a strange anticipatory quality to it because it seems as if it represents the dehumanizing images of Google Earth twenty years before they came into being. Finally, there is a sort of face that petrifies and fades out, or at least that is how some spectators experience it. This artwork is a telescoping of spatial and temporal scales that could only be achieved in painting by means of abstraction.

You also refer to the Situationist movement, to Land Art and to performance art, all of which are seen as a form of human disappearance, since they can involve becoming one with the environment and losing oneself in it. You yourself experimented with performance in In Memoriam: 10 ans/10 heures, going against the notion of ‘disappearance’ and plunging into the depths of your personal memory. Was remembering sensations, emotions and events a way of making you feel individual and alive? What was the aim of this approach?

I never thought that the few performances I did in very confidential settings, at Le Générateur (the Gentilly art centre), were particularly linked to my intellectual research. But in fact, in 10 ans/10 heures, the protocol was one of dizzying self-isolation. Without having rehearsed, without notes or support of any kind, without a time reference and without an audience – for the first five hours at least, when I was talking to a camera – I set myself the task of recounting without interruption, from 2pm to midnight, the last 10 years of my life, trying as hard as I could to stick to a chronological order. It’s hard to say what the ‘objective’ was, but I can tell you that in the months leading up to it I was genuinely afraid of going mad, and that I came out of it a little changed…

10 ans/10 heures was, in its own way, a quest for the living: in a conventional way, it was a question of awakening and verifying what lives in oneself through memory and what a raw exercise of memory is capable of arousing in terms of bodily and emotional reminiscences. More singularly, it was also an individual affirmation of the mnemonic capacities of a human organism in the face of those of machines. I’m not fooled: what we call human memory and computer memory do not fall into the same categories. And yet, on a personal level, I am tormented by that feeling of Promethean shame described by Günther Anders in The Obsolescence of Man: what a prodigious mass of information machines are capable of storing – entire universes – compared with my own capacities… It is distressing and – I repeat – shameful for me, as a historian, to see how quickly I forget. I’m not exaggerating.

At my level, this performance was somewhat extreme. I realise how modest, if not derisory, it is compared with what Robert Smithson, Bas Jan Ader, Richard Long, Piero Golia, Francis Alÿs, Abraham Poincheval and others have done or are still doing. These artists set themselves adventurous protocols, in natural settings that can be hostile, and their work is tense between a reaffirmation of their humanity – through the choice of and respect for a concept, then through its physical realisation – and its dissolution in environments that overtake, threaten and downgrade them. These are artists who put the human in the distance.

SURVIVALISM IN ART

As a historian, you look to the past, but you must also look to the present. At a time when our society is reaching new heights in terms of the ‘cult of personality’, individualism and the dissemination of its icon, and when humanity is exponentially pursuing its quest for omnipotence, what are the artistic signs today that return the individual to his modest, anecdotal position?

Indeed, I never claim in my book that art has become predominantly that of a ‘Universe without man’. On the other hand, I am convinced that many excellent artists – in fact, some of the best – intuitively propose alternative narratives of the world. Sophie Ristelhueber’s work on war, for example. More generally, I’m struck by the way in which popular culture capitalises on the fragility of the human being. In my view, we should be talking about an era marked by the ‘survival industry’, which is reflected in literature (Max Brooks’ The Zombie Survival Guide), comics (the appalling manga Attack of the Titans), cinema (Roland Emmerich’s films) and, more than ever, video games, where a plethora of titles – ever more ingenious – are released year after year (Survive the Nights, for example).

To conclude, we would like you to reflect on the question posed by Maurice Maeterlinck in 1890: ‘Will the human being be replaced by a shadow, a reflection, a projection of symbolic forms or a being that has the appearance of life without having life?

In fact, when Maeterlinck asked this question, he was thinking of the theatre, whose forms he was seeking to completely renew. In this case, he was inaugurating a fascinating artistic enterprise, about which there is still so much to be written and thought: that of a stage without actors, a possible laboratory for a ‘Universe without man’. Science fiction literature and cinema are full of this idea. Because I can’t talk about everything, I didn’t quote Adolfo Bioy Casares’s The Invention of Morel (1940) in my essay, but he proposes a very similar idea: on an island, a scientist invents a system that records the movements and behaviour of tourists and then transcribes them with the illusory precision of holograms, so that an exiled and isolated narrator believes he is seeing real people, even falling in love with a woman who is in fact dead…

This is perhaps the most dizzying aspect of the ‘Universe without Man’: human beings have had such a propensity to represent themselves, and with such a quality of illusion, that their projected shadows – busts, photographs, films, paintings… – could ‘survive’ for millennia after the disappearance of human life. All that would remain would be signs promising the Human, but with no one left to conceptualise what the Human is, not a promise, not even a sign.

This article was originally published in November 2017 in Stream 04 magazine.