Landscape as Urban Mediator

- Publish On 19 November 2017

- Anita Berrizbeitia

- 5 minutes

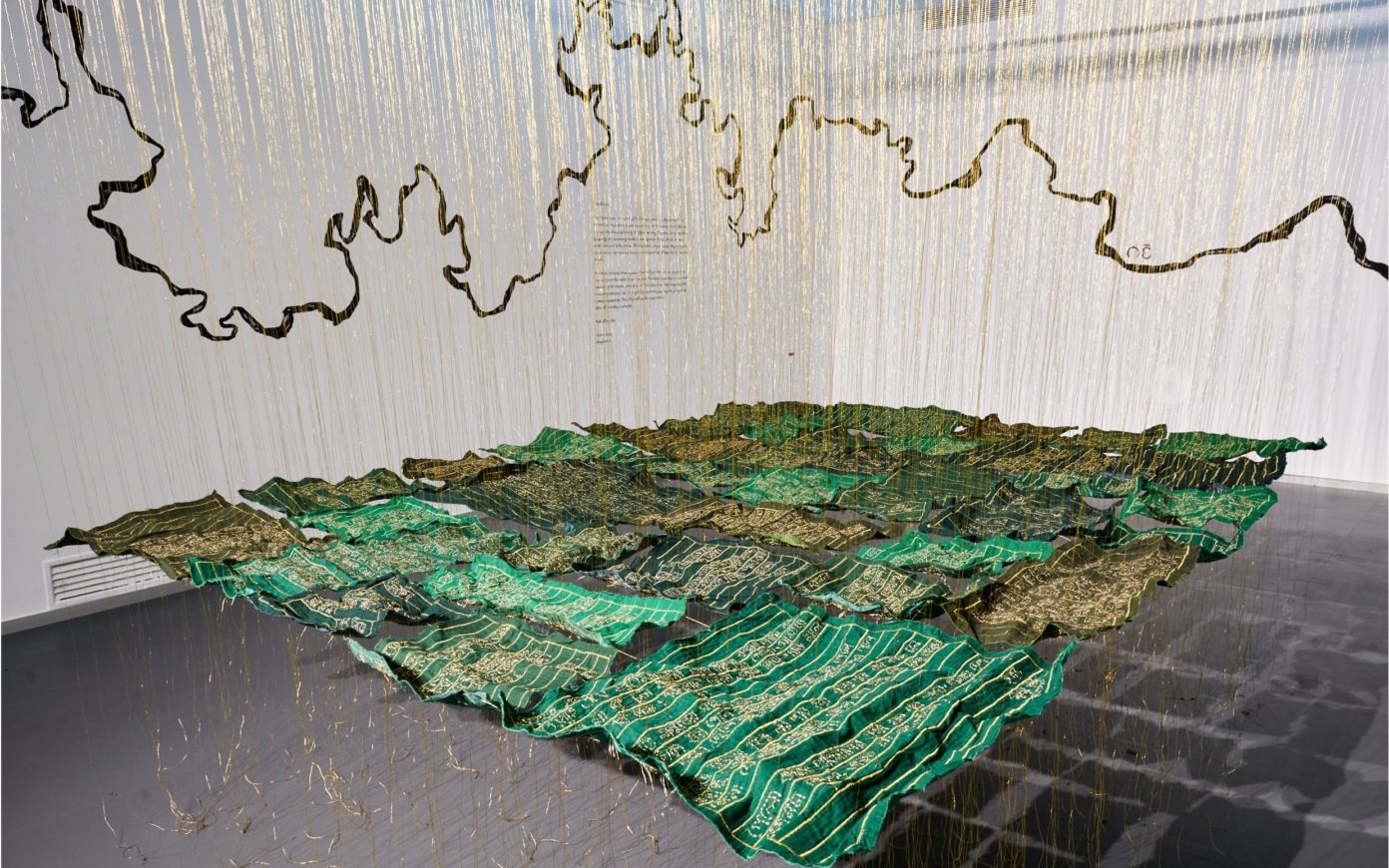

With the return of the living to the urban space, the landscape—as a discipline—has become a fertile conceptual framework for architecture. Landscaper Anita Berrizbeitia explains the way in which her activity explores the dynamics between nature, the economy, and society. From simple adjunct to the improvement of the conditions of urban living, the landscape extends its role to the redefinition of a city that goes further than multifunctional infrastructures to create complex spaces that contain multiple interactions and possess many uses. Resolving complex environmental issues requires an interdisciplinary approach, the establishment of international coalitions and regulations, but also the multiplication of citizens’ initiatives. Urban agriculture must also acquire a social and popular dimension so as not to remain anecdotic. It must shape spaces of production but also symbolic tools in order to develop our relationship with the environment through an increased awareness of where food comes from.

Stream 04 is investigating the theme of the living. In the context of the Anthropocene, we are exploring new kinds of interactions between humanity, technology, and nature. We have for example spoken with philosophers Graham Harman and Timothy Morton about object-oriented ontology (OOO) theory. Landscaping appears to be another very interesting point of investigation, because you are working with living natural elements.

Landscape architecture is the kind of mediating framework between what we know as “nature” (in the sense of natural processes), and society. In fact, we could say the intellectual project of landscape architecture is to understand this dynamic between nature, the economy, and society. Landscape architecture comes in to give organization and to mediate between existing natural processes (hydrological structures, environmental structures, ecology), the economic operations that define the city, and of course, the needs of the society that lives and works there.

Landscape is both generative of and supportive of urbanization and of capitalism, but it’s like Janus. It has always had this double-gaze: one that wants to support urban processes which are fundamentally instrumental and productive, and another gaze which tells us, “Let’s give shape and direction to those forces of capitalism so that they don’t get out of hand, so that it’s not just about maximization of efficiencies and profit, but also about sustaining culture, quality of human life, and now, of course, the climate and the health of the ecosystem.”

Landscape architecture, which started very much as a discipline to improve living conditions in cities, is now expanding to address a greater set of challenges because although cities cover a very small percentage of the earth’s surface, they cause the most damage. For instance, we cannot continue to have mono-functional infrastructures. This speaks to your point, “We have been separating humans from nature.” Well, the city has also, through zonification, had very clear divisions between recreation, commerce, housing, production, and infrastructure. We cannot do that anymore. We have to make everything in the city that relates to landscape do two or three things. For example, the Transportation Department has to get into forestry because highways might need to—as cars disappear—become forests. In the future, we will have more typologies of landscape space, more places that landscapes can inhabit, and more challenges that can be addressed through landscape.

From a theoretical point of view, are we close to a conceptual breakthrough, like rethinking the non-living? Like looking at the building, no longer as just an object, but as a metabolism? Are there ideas like that developing in response to anthropocentric concerns?

We are feeling the effects of climate change everywhere. You see it in the fact that we have flooding problems everywhere, not just at the edges of the water. The world’s coastlines are all at risk. The United States, for instance, has urbanized primarily along the coastlines without proper planning. But we can also see it in the way that species are reacting. Take the example of the sugar maple. Everything that’s beautiful and in color right now in New England is probably a sugar maple. This tree has formed a part of the local economy and with climate change, it has become very brittle. So how do you begin to rethink big forest plantations when the species are dying? We have a similar problem with hemlock. A native evergreen that grows from Canada down to the mid-Atlantic, it is also dying and causing massive deforestation. I’m not sure that we are responding quickly enough, or that we even know what to do, but there is rapid, large-scale change everywhere.

In Boston, the conversation has been, “Individuals have to respond on their own because the government can’t respond soon enough.” This is the interesting thing about the Anthropocene—everybody has to respond and act accordingly at a personal level. We’re going to need top-down agreements and international coalitions. Last week, many countries agreed that they’re no longer going to use the refrigerant fluid that is used in air-conditioning around the world, as it is one of the major causes of greenhouse gases. These kinds of very top-down solutions are going to have to be implemented very quickly. But just as necessary will be grassroots initiatives that will need to be extensive and deal with how we live differently on a day-to-day basis.

In your research, what are the options and strategies that you find most effective?

We deal with these topics across all departments at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). Food and food security is another challenge we explore, for example, across all programs. Questions of energy, food, climate, waste, water etc., are all issues that not only transcend disciplinary boundaries, but also require multiple instruments in order to address them. I find that the most effective way of working is in an interdisciplinary way, because complex problems require multiple frameworks and approaches.

They’re a part of architecture, and of planning, and of landscape architecture—so we are all thinking about this together. This is why it’s exciting to be here at the moment. And because we have an experimental approach at the GSD design studios, we are inventive with questions such as, “Where will the forest of the future be? How do you replace a forest that has died because of climate-related issues? How do you think about the interface between the city and water? How do you live in that city?”

A mediating framework between nature and society

One aspect that is connecting the food debate you mentioned with nature in the city is the question of urban farming, an area in which we have seen a huge rise in Paris. What is the future for urban farming? Is this just a trend, like a fashion, for a creative class? Or is there a real sense of moving toward local food production?

There’s a future there, but we need to think creatively in order to make it happen. First, urban farming needs to be scaled up if it’s going to be affordable, certainly in this country. Urban land is very expensive, so where is urban farming going to happen? It’s not necessarily on the ground. Here in Boston, we have urban farms that are very old and historic and those will probably stay. But they only feed a very small fragment of the population. An excellent alternative we have developed in the United States are CSAs—Community-Supported Agriculture— programs. With CSAs, if you are in any city that has farms on the outskirts you can buy a share in this farm. Once a week you receive your share of fruits and vegetables. It keeps the farm in business and it supplies people with fresh food.

In some cities, like New York, they have expanded that program so that people supported by the government through food stamp programs will have access to healthy food as well. Of course, this is an issue of health, too, because we have a great crisis with obesity due to the lack of access to fresh food on a regular basis.

This is a multidimensional problem that is intractable at every level. But we have been able—either through local, municipal, or state-wide initiatives—to start to move in the right direction. For instance, New England, in colonial times, was an agricultural landscape and some of those historic farms have been preserved. When the agricultural economy went to the Midwest, everything returned to forest because a temperate zone always tends to forest. So, in New England, we’re constantly battling to find a balance between forest and agriculture.

One case of different institutions working together to expand the reach of local agriculture is an organization called Gaining Ground, which runs an organic farm in a historic landscape. The products of this farm go to feed the homeless, and the labor to cultivate, harvest, and distribute the produce comes from volunteers, many of them students from the local high school that need the hours in order to graduate. So here you have an educational requirement, a social need, and a preservation issue—the homeless and access to food with historic preservation—converging. This is the future: thinking transversally to expand the applications and relevance of our organizations.

It’s not only spaces, infrastructures, and buildings that cannot be mono-functional anymore—our institutions also need to become porous; meaning, the Parks Department can’t just be about recreation. Or the historic commissions cannot just be about preservation. All of the institutions that support the existence of all of these different landscapes in our society need to expand their mission. It’s not easy to do, but I think it’s going to happen, there are remarkable examples of what small farms can do. Roofs also have great potential, especially in this country where we have big-box stores.

You have been working a lot on this subject of urban agriculture?

Absolutely. Farms inside skyscrapers, hayfields inside skyscrapers… Some of the big-box retailers are also starting to lease their roofs for photovoltaic energy, and this is fantastic. That means that there is some profit and we’re also not totally dependent on the cost of fuel. I think that’s going to happen with agriculture. These roofs need to be designed in the future to do this. In Brooklyn, New York, there are farms on top of very large roofs. I think we need to make them social, to make them the new parks and spaces of production to educate people. Because when I say this needs to be a grassroots movement, people need to understand where food comes from—that is not an abstraction. The problem is that the human-environment relationship is very abstract so nobody understands where milk comes from or everything that needs to happen for milk to get to your table.