Peri-Urban Land Stakes

- Publish On 19 April 2017

- Michel Desvigne

- 10 minutes

The city of the Anthropocene boasts a new relation to nature that emerges from the elaboration of a novel continuum between urban spaces and the biosphere. This living dimension, which has long been suppressed by modernist planning schemes, has nevertheless always been at the core of the work and of the practice of landscape design. Michel Desvigne speaks of his attachment to the physical dimension of things, of how he envisions urbanization as a landscape designer and of his work on peri-urban territories and scattered housing—a key urban issue that he seeks to “mend” by working on the “lisière”, the intermediary landscape situated between the city and the agricultural landscape. He calls for a more significant commitment on behalf of public authorities, but also for a new vision for agriculture.

Michel Desvigne is a landscape designer and architect, director of MDP Agency, Grand Prix in Urban Planning.

Stream : In this issue, we are exploring the challenges of global urbanization and we are curious as to how a landscape designer envisions this type of phenomenon.

Michel Desvigne : It seems to me that our profession is first and foremost defined by a major interest in the physical thing. Our mission is to be capable of seeing, understanding, and measuring the physical thing and then possibly transforming it. I am genuinely interested in the physical thing. I am of course aware of the immense difficulty of seeing, for starters, and then of understanding and measuring the physical reality of territories, and in particular of our present urban spaces. That is probably the major issue for me: how can I see things without being blinded by any form of belief, certainty, or prior experience? Clearly this has to do with the concept of space-time. I travel a lot—it’s almost part of a healthy lifestyle—probably around one hundred work-related trips each year, and I need that to continuously recalibrate my perception, failing which I wouldn’t be capable of measuring anything. If I complacently watched Parisian rooftops through my window, I wouldn’t see anything anymore. We have to recalibrate our perceptions to be able to make sense of what we see. I need to explore, that is to see, and especially to see by comparing. As soon as I stop doing so, I lose any proficiency I have. Seeing is the biggest challenge.

Scattered urbanisation

Regarding urbanization, I am of course aware that the majority of the population lives in urban environments but I also read that a lot of people live in towns which aren’t really towns, living more than half a mile away from their school, their workplace, and from shops. It is more than simple suburban growth: this scattered housing is where a large part of the population lives, at least in Europe and the United States. I do not know the figures but I indeed see that the population is becoming urban, so, by default, it ceases being rural and linked to farming for instance. Nevertheless, is it really urban? And what kind of city are we talking about? When I touch upon this with my fellow urban planners, it is obvious just how difficult it is to answer these questions, to quantify this scattered housing. It seems that electoral outcomes give an indication: electoral maps quite precisely overlap what we have called in France “rurbanisation.” But the term is a misnomer. Another phenomenon is at play—building further away, cheaper, in the middle of nowhere—which has become massive. I am convinced this is a major subject. It is said that this is becoming a social time bomb—in fact, Laurent Davezies points to it as a key factor of the upcoming crisis he describes in La crise qui vient. Part of the population is experiencing high levels of insecurity—they will be incapable of finding new jobs and getting proper training, and those who have invested in real estate will find out it does not necessarily have any real value. We therefore keep coming back to the same question: what city are we talking about? Is it a city or is it some sort of population transfer to kinds of “involuntary ghettos?” I do not perceive any manipulation but, due to a lack of vision, a lack of will, we find that society is really falling apart.

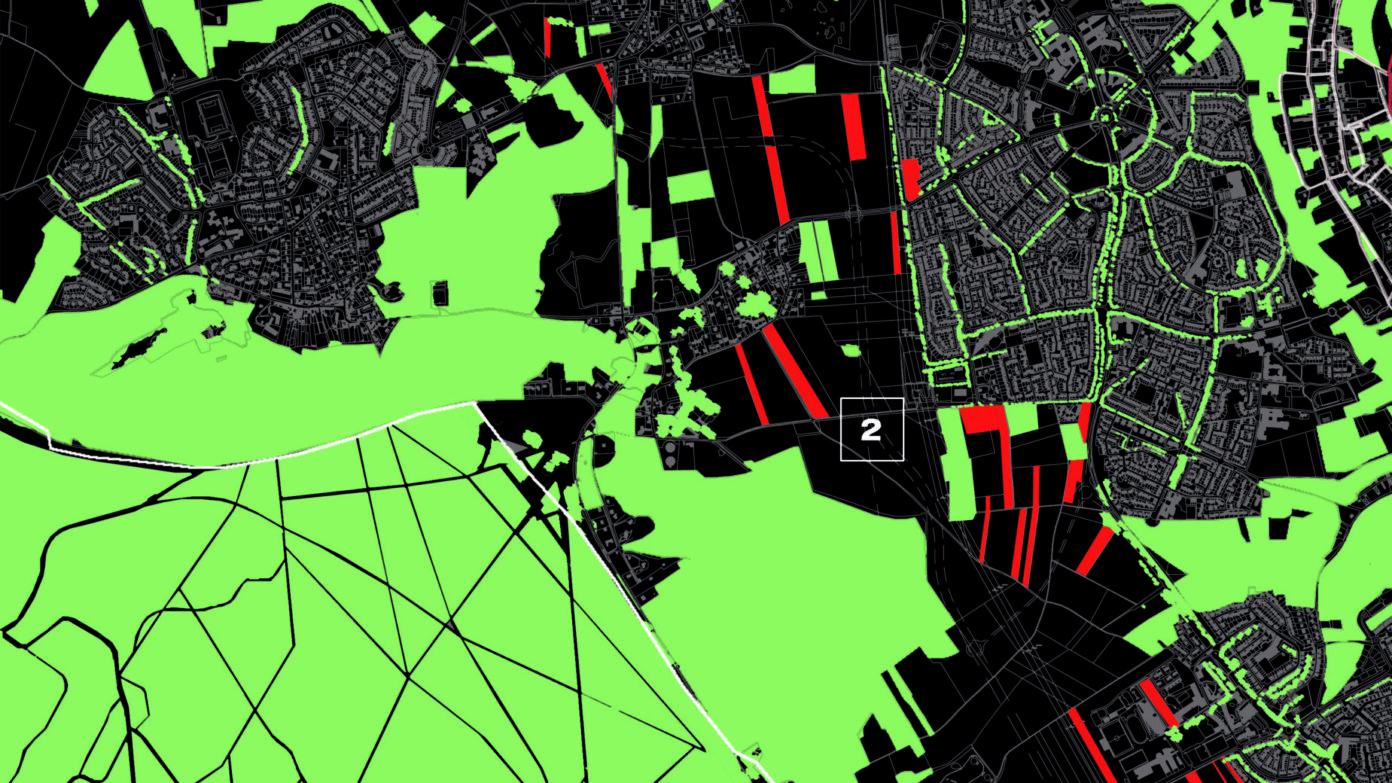

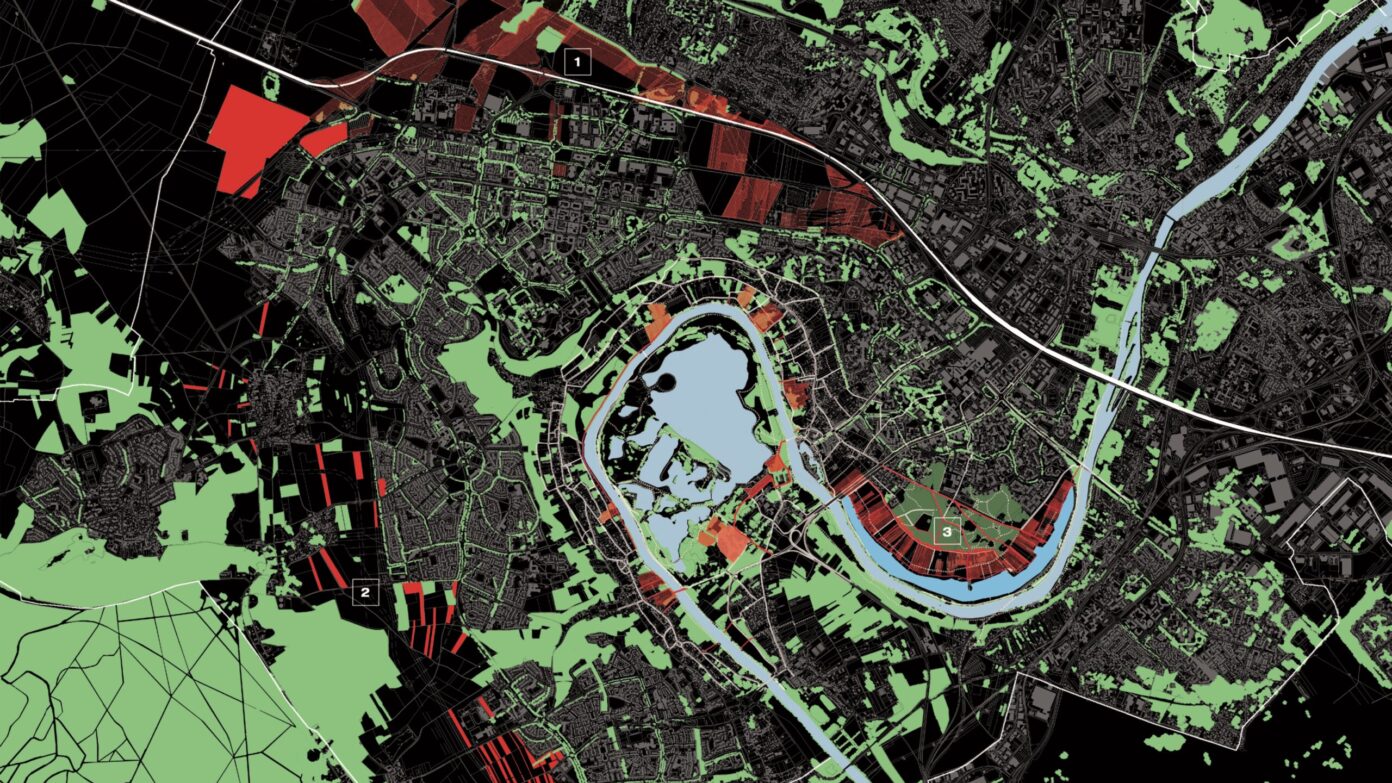

I am very interested in the urban metabolism, probably because the maps which are drawn by scientists help us find the appropriate scale and focus. It is sometimes difficult to go from the scale of a block or a building to an entire city, but departing from this built urban environment to replace it within an agricultural landscape is even more difficult. These successive adjustments are nearly impossible. We are confronted to this difficulty in Saclay, where we are building neighborhoods on vast territories. The questions we ask ourselves and the way we look at farmland are very different according to the scales we are considering. For instance, 5,600 acres of agricultural land have been granted protected status. If one stands back and takes a broader view, this figure pales in comparison to the total farmland in the Île-de-France region. The question of scale is paramount and acting demands a remarkable adaptability: we therefore need these maps. What does scattered housing really represent within the agricultural landscape? It is difficult to draw an accurate picture of these physical realities when we fly over these territories.

Inherited plots

Stream : How would you define this physical reality you talk about?

Michel Desvigne : Let us go back to agriculture. It is important and still occupies a major part of the landscape but economically it hardly represents anything these days. It is an agriculture that has been turned upside down by mechanization and continuous re-parceling, which is still ongoing in places. Farmland is relentlessly transformed and reassembled. This is a physical reality—this upheaval is visible no matter where you are. When we are moving around—something we do constantly, be it by car, rail, or plane—we see farmland which is the product of policies that have led to re-parceling. It is not the work of agronomists—the agricultural landscape is now rarely the result of physical practices. The ownership of parcels as well as a number of technical practices (harvesting, watering, sheltering from the wind, animal husbandry) shaped the agricultural landscapes throughout the world. However, since the 1970s, land re-parceling is first and foremost carried out for technocratic reasons: the critical size of a farm is defined in view of its profitability and the number of people per acre is defined according to mechanization. This agricultural land has thus lost all connection to human territory. As a matter of fact, it also has many technical difficulties: low wind protection, poor drainage, the risk of flooding, etc. Nowadays, we sometimes try to rethink the re-parceling but with a nostalgic vision which, as it is the case, is not effective. Those who study agronomics are said to be presently divided: there is a sort of schizophrenia between financial cynicism and a sense of nostalgia—the idea of coming back to a supposedly ideal state. In any case, few of them seem to be interested in the phenomenal capacity to shape a landscape for the future.

In Saclay, we are working with the agronomy school INRA (the National Institute of Agronomical Research) and are trying to find experimental solutions to provide better quality to our agricultural and peri-urban territories. But right now, I feel our research is paltry and disconnected from actual practices because a large part of our contemporaries live in a landscape dominated by agriculture without having the slightest physical relationship to this land. Re-parceling has partly eliminated the lanes behind the houses which made it possible to enter into the countryside and the model of suburban development has created no connection at all between the last remnants of the ancient agricultural land parceling and these new neighborhoods. This explains the paradoxical situation whereby many people live in the countryside without having any relationship with it. Again, it is not a question of feeling nostalgic: our countryside has been completely transformed by a series of land consolidation schemes lacking any vision, any architecture, any project, with retail developments which have often been imagined only by surveyors and project developers. We are now in presence of towns with no urban planners, no architects, no agronomists, and perhaps even no farmers able to give shape to the landscape. I do not think there is a state of reference to which we should come back, but given that this agricultural landscape has been transformed, why haven’t we taken the opportunity to build some public space? I believe this is a very important question.

In the suburban city, public space is virtually nonexistent, with the exception of a turnaround or a public square from time to time. Our society hasn’t built adequate public space for these cities which take up a large part of the land. Nowadays, when we build a project, we try to respect certain ratios—30% of public space, with 15% dedicated to roadways and city squares, and 15% to parks and gardens—but when we look at what was done during the twentieth century, that 30% was clearly not respected. Our generation has seen this phenomenon unfold with an utter helplessness. I therefore think we should take much more interest in public space.

The missing public space

I therefore think we should take much more interest in public space. I am fundamentally an optimistic person and I think that with some effort we can correct and upgrade things because this situation affects millions of people. And what means would be used? Those of agriculture: transforming agriculture on the outskirts of cities will not save the planet in terms of food production but it will probably improve the quality of life in those cities by acting as the missing public space. Jean Nouvel was kind enough to include some of my ideas on the subject in his thoughts about the Grand Paris (Greater Paris) project. In particular, he used the term “lisière”—the French term for the boundary of two habitats—which is probably too vague, but underlines the necessity to establish firm roots within the landscape: the aim isn’t to form a green belt but to create a minimum amount of public space so that the city can be a place where it is possible to go for a walk, to move around, and to maintain a direct rapport with the land. Nouvel went so far as to imagine a “lisière” law, in the same way as there is a coastline law, i.e., a set of processes to carry out when we are at the borders of the city, facing this agricultural landscape.

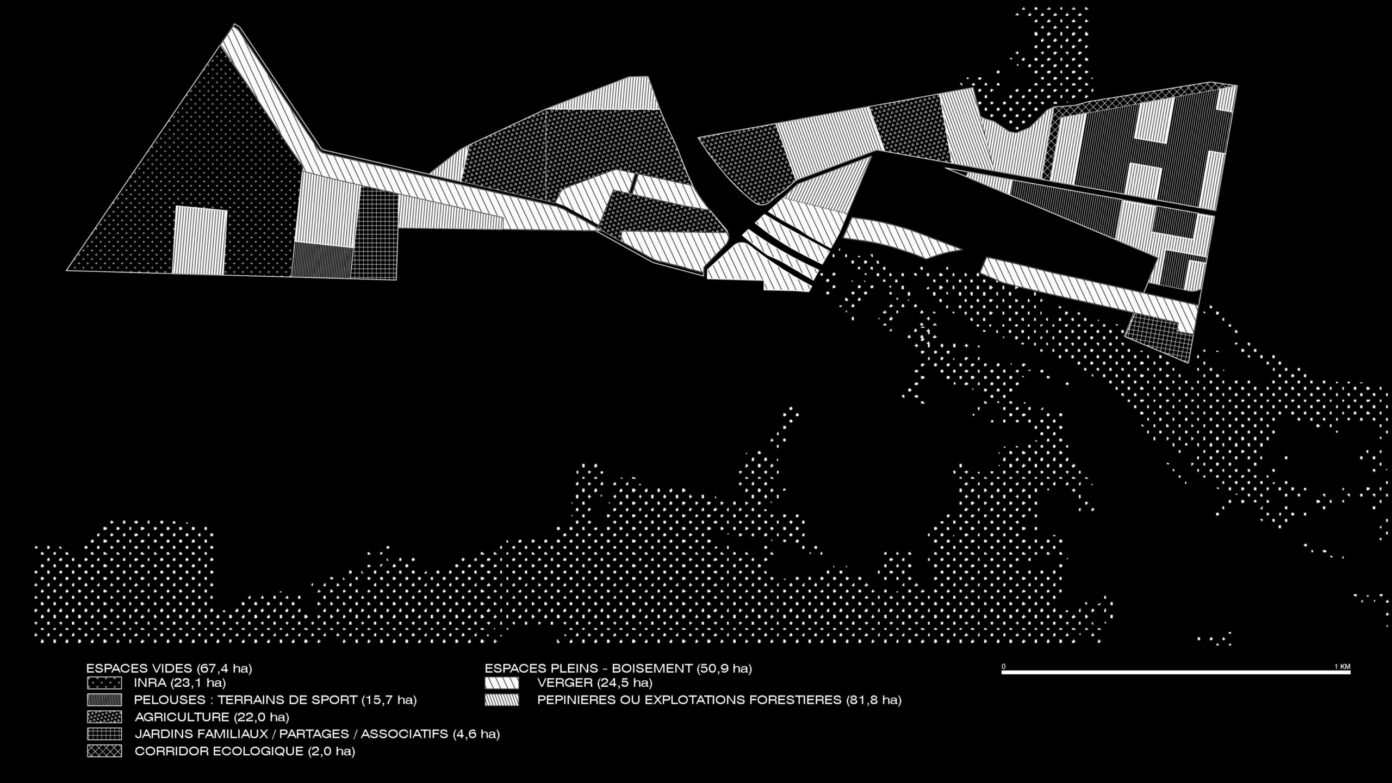

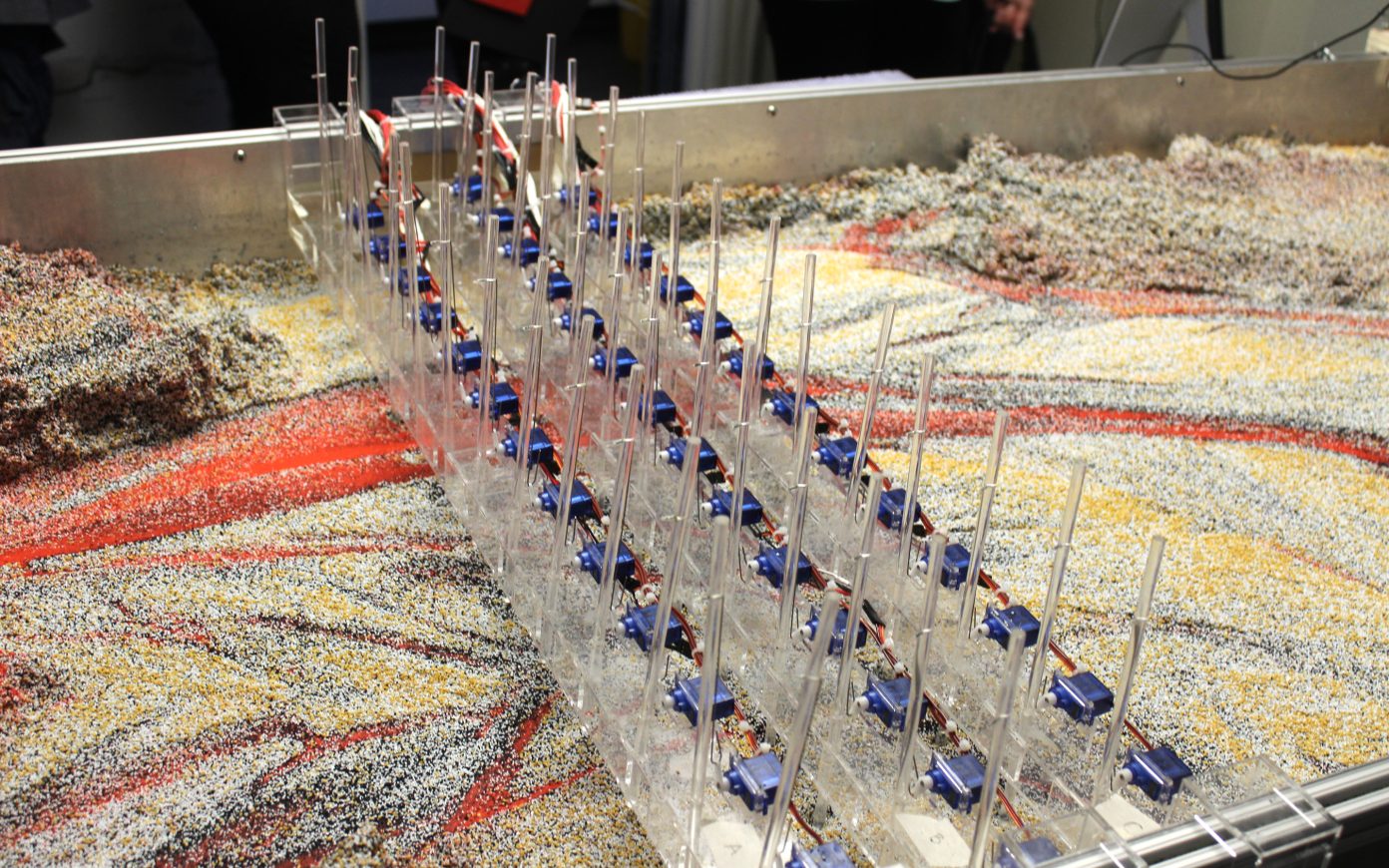

The great threat is of course the development of slums and economic insecurity. It must be a true public project, solid, drafted, and designed, something that has yet to be invented. We are carrying out a few experiments which seek to do that in Saclay: we are conceiving a system of parks between the campus district and the large expanses of farmland. Thanks to three years of lobbying, a series of orchards, woodlands, and lanes will be established. I am convinced that this is a real blueprint for society but I find it very difficult to convince politicians to get interested in the subject.

Agronomics is the only lever and these projects must be financed by slightly more profitable agronomical practices at the local level. This cannot be governed only by urban policy. That is what we are trying to do in Saclay: to free up a zone between protected agriculture and dense districts to make this landscape, which I call intermediary, the prototype of a set of practices. The idea is to densify so as to free up some land which isn’t deemed to be farmland on which miniaturized agricultural practices can be put in place to create intensity and to build public space.

I have published extensively on the subject and we have presented conferences throughout the world and it seems that it is of interest to the community—I was probably awarded the Grand Prix de l’Urbanisme on the basis of these ideas—but, unfortunately, in practice it still hasn’t had much impact.

Stream: To clarify, the idea is to recreate public space through agriculture?

Michel Desvigne: Yes, I am probably not giving enough examples. There is this slightly mythical image of the medieval or Italian Renaissance city with a continuum going from the house to an open territory: behind the house, there is first the decorative garden, then the vegetable garden, the orchard, a few communal meadows and then at last, the open countryside. The landscape becomes gradually denser and we can see some very thin connections. It can still be seen in some small towns in Umbria. There are a few obvious physical transformations to carry out: re-densifying the network of hedges and paths to introduce a finer scale, market gardening, human presence, greenhouses, etc. It is a true blueprint for society which probably entails public investment. It would involve bringing intensity to the urban periphery without expecting actual profitability, at least in the short run. This isn’t an activist landscape or nonprofit tinkering, but again, a true blueprint for society. I think this should be a public responsibility and its drafting should be imbued with the dignity, power, and possibly the magnificence of public affairs.

I would really like to work with agronomists on the subject: is this a genuine working assumption or is it a desperate move? I am personally convinced of the value of that physical reality. I see it when I go to Ticino: a domain where vineyards are relatively precious, where urban areas are strongly embedded in the agricultural world. To state things more clearly, in towns such as Bellinzona or Mendrisio, one can find vineyard plots and some orchards right in the middle of town. This embeddedness is strong because everything has value—the city as much as agriculture—and there is beauty in this approach; it is honestly an enviable way of life.

People know their territory well, unlike new country dwellers whose only link to the farmland is the mall where they buy their garden shed and who develop practices devoid of any beauty because they are not founded on any skill or culture. This is unacceptable and something we must improve on. I cannot claim to be a landscape designer without having any interest in the subject. Since the postwar years, in Europe, engineers have taken control of the land: of infrastructure, agronomics, urban planning, and construction, there is no need for architects any more, so to speak. The field has been completely confiscated by engineers and industrialists. Must we, landscape designers and architects, resign forever and be contented with very beautiful but powerless images, or do we have some sort of responsibility to our fellow citizens? I would lean towards the obligation to act.

This article was published in Stream 03 in 2014