Toward the Aerocene Era

- Publish On 7 October 2021

- Tomás Saraceno & Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel

- 8 minutes

Artists experience the shared condition of being both protagonists and victims of the Anthropocene, and therefore see their role dramatically altered. For Tomás Saraceno, the exceptionalism of the artist’s position matters less than the catalyzing of new ways of thinking and inhabiting the world. The aim is to find solutions by collaborating with humans and non-humans, as in his installation set up with Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel, where spider intelligence took the forefront. Such new rituals of encounter with art endeavor to highlight relationships with the Earth that go beyond an ethic of extraction. With the alternative epoch of the Aerocene, Saraceno works along with an interdisciplinary community of artists, researchers, and citizens in order to break free from the Modern narrative of division and offer concrete alternatives, as with the experience of the flight of the Aerocene Pacha, in collaboration with the elements and local populations.

What role does the Anthropocene play in your work?

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel: As a curator, my work is less concerned by the Anthropocene than by what comes after, which means that I see art and artists as enablers for new ways of thinking, sensing, and perceiving the way we inhabit the world. I am not interested in commenting on the Anthropocene and anthropocentrism so much as I am in exploring these alternative ways of sensing other sensibilities and sensitivities. I believe that artists are among the last remaining guides engaged in imagining alternative and desirable futures. Many artists have been mobilizing around the Anthropocene and providing commentary on the way humans have been destroying their environment but I never really was interested in the artist’s position as someone who produces commentaries on the world we live in however, but rather as someone who enables us to “go beyond,” to rise above settled positions and open up new perspectives. Tomás Saraceno’s work on a new era called the Aerocene is an important example of this. His position is to basically take notes on the current situation, to consider where we are and where we are coming from, but not to stop there, but rather to imagine other ways. The Aerocene is very much a revolution in the way we move around in the world. It also illustrates the way we behave and build relationships with the Earth and natural resources by erasing the almost entrenched behavior of using predatory extractive and capitalist means and tools to depict and perceive the world.

Tomas Saraceno: I have been fascinated with astronomy, cosmology, astrophysics, and by the unfathomable scale of spacetime since my childhood, and all the more so given that I come from a family of scientists, with my brother and my aunt who studied quantum physics. These topics have always inspired me and I very much view the Anthropocene as resting on understanding how the various scales of time and space mesh with one another. Its very name is a way of saying that we live in an era where certain humans are now a driving force in the abrupt change in the conditions of the habitability of the planet. Today, the real question is whether and how we can find a way out of this situation. Few profit from the sustained abuse of life and land, yet we have seen just how drastically an ethics of extraction, extraction of data, of resources, of capital, have impacted indigenous communities, nonhuman life, in short the lives of our neighbors. So we have found ourselves set with the hefty task of formulating a response to these wide scale problems, which is something I know we can only do if we come together and think collaboratively.

Working together with humans and nonhumans, with spiders and webs, we have imagined a solution: a new era, which we call the Aerocene. It provides a way for me to anticipate a space-time I would really want to live in, because continuously thinking about the Anthropocene is simply too depressing, I feel guilty and it is something I would rather not be a part of. In a sense, the Aerocene is a work of art that develops over time and space with potential consequences on a geological scale.

There are already many alternative “-cenes” out there, but I hope the Aerocene will succeed in not only in sparking our imagination, but also in inspiring change, especially in the elite minority that is on the driving seat and causing the consequences that are borne by the broader majority in a world that is more unequal than ever. Our purpose is to manage to convince part of the human population to attune itself to the world and change its habits rather than the climate, ultimately doing everything activists tell us we should be doing but using a different rhetoric.

We are all aware of global warming and climate change, but it is clear that our political systems are failing to address it, but also that there is no single discipline that can, alone, grasp the scale and complexity of the phenomenon. Be it in art, science, or architecture, we are locked in silos of encapsulated comfort zones, and my work consists in trying to find a way to extend the knowledge spectrum, to move out of these comfort zones and bring disciplines together to start new conversations.

Are you under the impression that this change of era is also transforming the paradigm of creation? How does it change the role of artists in society?

Tomas Saraceno: Generally speaking, I always strive to form part of a movement and not to dwell on differences or on the exceptionalism of who I am or what I can do as an artist. What I’m interested in is similarities, exploring everything that could help connect individuals and approaches. In a sense, even being different helps connect to one another, because it opens potentialities and synergies. My way of thinking and working is to look for contact points between disciplines. We are all different, but it is my belief that we could nevertheless somehow work together, gather together around projects. And I do it with humans, but also with non-humans, with dust or spiders—I’m fascinated with spider intelligence—because it seems to me that the discourse of the Anthropocene has accelerated the urgency of the need to understand other realities, other points or webs of view.

To give you an example, one of the projects I’m most happy about, Aerocene Pacha, emerged from an invitation by BTS, a huge K-pop band. The band itself is a global phenomenon. I think they’ve sold more records than the Beatles, though I had never heard about them when they first contacted me. At any rate, it was my first project that wasn’t directly coming from the art world. As part of a global exhibition, Connect BTS, DaeHyung Lee acted as a curator, inviting various artists from all over the world. When they offered me to create an artwork in my country of origin, we chose to go to return to northern Argentina, in the province of Jujuy, where I produced a series of artworks in 2018 through the support of CCK. I knew there were huge tensions and struggles around lithium extraction there. The salt lakes in this region, in what is called the “lithium triangle,” between Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, contain 70% of the lithium reserves of the planet. Lithium is used, among other things, for electric car batteries as well as in almost all the devices of the “green revolution.” But there are very strong tensions between the multi-national companies and the indigenous populations, as extracting lithium plainly destroys their way of life. One ton of lithium requires two millions of liters of water, resulting in huge amounts of pollution and waste, just as with fracking. In Jujuy, the atmosphere is very dry and there is very little rain, and all the agriculture there and the indigenous way of life relies on the scarce water resource. But now, large corporations are coming in to extract all these minerals with the same colonial mindset as five hundred years ago—nothing has changed—and this leaves the local communities with very little possibility for self-determination.

We decided to create a flying sculpture based on the principle of the hot-air balloon bearing a slogan, “Water and Life are Worth More than Lithium” written with the communities of Salinas Grandes, Jujuy, Argentina. The flight of Aerocene Pacha took place completely free from fossil fuels, batteries, lithium, solar panels, helium, and hydrogen. It marks the most sustainable flight in human history, and one of the most important experiments in the history of aviation.

The sculpture rises up thanks to the difference in temperatures generated by the hot sun, in other words thanks to the collaboration between the sun and the atmosphere, and our collaboration with them, but also thanks to dialog and collaboration between humans. Together with the communities, we carried out the Pachamama ritual, thanking Mother Earth and asking for its blessing. There, in the salt lake, was a meeting of different cultures and generations, with Korean and Argentinian youth, joined in singing to BTS songs in Korean, as well as people from the art world, friends, and family. It was really wonderful to see all these people work together, especially since we were conveying a very strong message with the indigenous communities, a message all could see lifted off into the sky.

We received the confirmation from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) that this was the most sustainable flight in human history, more than those of the Wright or Montgolfier brothers, or than anyone who has ever managed to lift themselves into the air! FAI, based in Lausanne, is the authority for air and space flight. For over a century they have recognized the most important accomplishments in air and space; awarding world records to individuals such as Peter Lindbergh, Maryse Bastié, Yuri Gagarin, the crew of Apollo 11… For the Pacha project, these 32 world records also represent the profound contributions made by the communities of Salinas Grandes. The exchange of local knowledge and the struggles faced by the native communities as a result of the extractive lithium industry that now plagues the region was central to the narrative of the Aerocene Pacha project, and defines the next step towards humanitarian action for the Aerocene Foundation.

Aerocene Pacha is also an example that proves that technology could, and needs to be, coupled with social coherence and decoupled from extractive energies. It illustrates the activist dimension of artistic work, which isn’t simply about generating emotions, but also about revealing prospects for concrete alternatives, coupled with genuine social coherence. Artists are now often increasingly wanting to contribute more towards welfare, redistribution, and equality within society. It isn’t only an artistic practice and we often diverge into crafting governance, the processes that will help shape our work. For instance, we experiment with practical solutions and share them around us, sharing all the information and data of the project in open source.

I believe that we must step up collective actions like this one on all fronts, not only be an artist or an architect and keep to one’s field. Being only an architect isn’t enough to really contribute to change things anymore if it ever was enough. We must engage in rethinking the way we’ve been designing and organizing in the West, open up to other disciplines, to other societies and other worldviews. Quite simply, we have to move beyond the silos in which Western modernity has enclosed us.

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel: Art has always been very much about reshaping sensitivities and our grasp on the visible. Somehow, since the earliest age of creation, even in cave paintings, we can see this deep need to represent and transcend, or to represent a transcendence of what can be seen and the power of what cannot be seen. Creation is derived from this urgent need that human beings have to acknowledge a reality that might not be as obvious or as tangible. The urgency of the time we live in includes an overwhelming discourse of catastrophe, of an impending Armageddon. This is producing a general state of panic or paralysis. The overwhelming attitude is that we’re too late and there is nothing we can do, a form of resignation. Certain artists have devoted their entire existence to alternative visions of the world, and I believe this posture is needed today more than ever. It is in such moments of crisis and severe lack of understanding of an overwhelming, radical situation that artists take on new relevance. Joseph Beuys was already advocating the social mission of the artist decades ago. His concept of “social sculpture” acknowledged the idea that the artist has a very special role beyond the art world, in broader society. This position should not only be embraced but encouraged, supported, and promoted as such. Marcel Duchamp had this posture where he wanted to permanently expand the territories of creation, art’s subject matter.

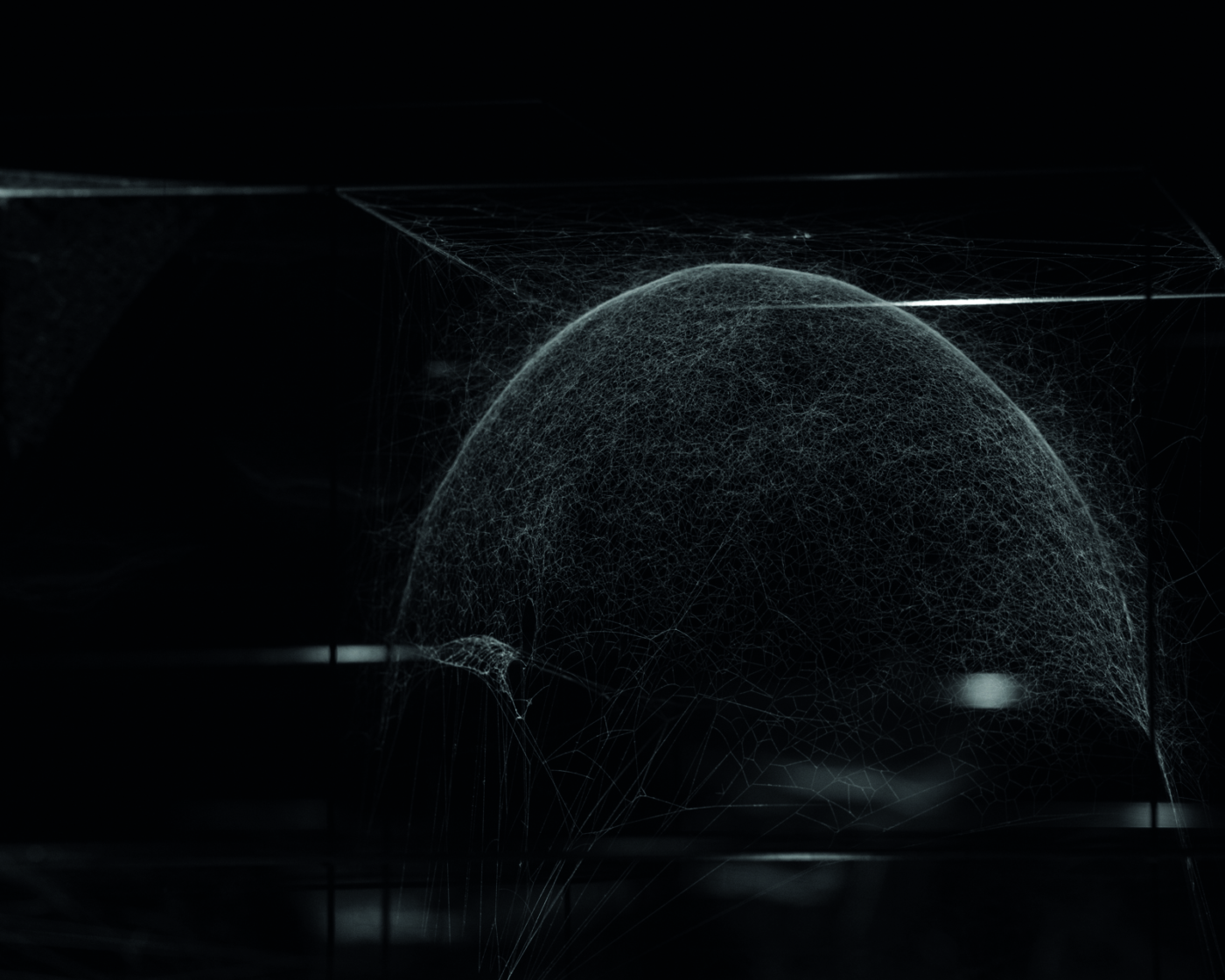

It seems that we may be becoming more aware of the fact that artists offer visions and perspectives that are further enriching us. For instance, one of Tomás’s projects for Carte Blanche in Palais de Tokyo built on the hypothesis that spiders can capture primordial gravitational waves with their webs, as they have developed senses that by far exceed those of humans. Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space that are hypothesized to be caused by colliding black holes. They were only first recorded in 2017, however, the hypothesis of Tomás is that spiders have been able to detect them since the earliest times due to their unique abilities. He had been working on this idea with various physicists, and is in fact still engaged in studying the potentialities of non-human beings. This is one of the projects where he overlays a very poetic and visionary hypothesis onto the scientific world with the goal of expanding our understanding of the variety and richness of life of non-human beings. In this sense, he embodies this idea of the artist that expands our understanding of the natural world and shows how boundless we could be as humans if we worked to develop other types of awareness.

I always thought that artists had a very special position within society, and I believe it’s the role of society to acknowledge that and let it happen. I’m terrified by the fact that what currently decides whether beings are considered worthy or unworthy of existence, whether shops and cultural spaces can open or must close is driven purely by economics and monetization. Our current model of society only recognizes financial and economic value, and not spiritual or mind-expanding value. We will have to ask ourselves a lot of questions about these decisions, because, beyond being indiscriminate and extremely unfair, it shows something much deeper about what kind of values we worship and support. I believe that artists are promoting values that are essential for us as human beings, and that, in these moments, they have a very special role to play which might not be unlike that of the Oracles in Ancient Greece. Like the Oracles, the modern artist is an individual who has a very special voice and is able to express some kind of truth or sentiment that we are blind to. The vision and perspective of artists is something that we should all listen to much more carefully.

Do you think this also entails considering and leveraging other intelligences, not only those derived from Western modernity?

Tomas Saraceno: I believe that by dividing ourselves from nature, we will never allow ourselves to become truly intelligent. So, yes, Let’s look at the spider /web with the “extended embodied intelligence” that arises from being attuned to our environment. Returning to the case of Aerocene Pacha, we needed to know the weather to prepare the flight because the sculpture can only rise up into the air when the temperature and sunlight are just right. My impulse was to look this up on Google, but this proved impossible, because I had no signal. Well, the people living there simply looked at the clouds and through this extended intelligence, they could forecast the weather based on their observable reality. This is an example of a very simple way in which somehow we have become dependent on a central machine system from which we must find ways of relating to ourselves. I grew up in Italy, and we have sayings like “Cielo a pecorelle, pioggia a catinelle,” meaning that when the clouds take on the shape of sheep, the rain will come. These are forms of knowledge that we used to have, but that have disappeared with modernity.

This ties in with my interest in the “embodied cognition” of spiders, because their cobwebs form part of this extended intelligence. Agamben and Von Uexküll talk about the “reciprocal blindness” in which each species is confined to, even though they are nevertheless capable of communicating with one another to a surprising extent. Spiders cannot see the flies and the mosquitoes, yet, in the course of evolution, the geometry of their webs shifted in such a way that flies continue getting caught in them as their own flying patterns change. Neither the spiders nor the flies can perceive the world of the other yet, somehow, they are sensing each other. Most human beings have lost this capacity to tap into the sense of others, this “response-ability,” as Donna Haraway calls it. Ants, for instance, are able to sense tsunamis in advance, so because humans used to maintain a relationship with ants, like a large family, with no separation, when the ants would suddenly start moving uphill, humans would follow, and no one would die. These are things that we are only slowly rediscovering, just as when we very recently discovered that dogs could sniff out Covid faster than any technology.

I visited a village in Cameroon located very close to the border with Nigeria where there is an age-old practice, of spider divination called Nggam. During Nggam, a specific set of binary questions are asked of a grounddwelling spider, whose response is interpreted via the spider’s specific rearrangements of the arachnomancer’s divination cards—stiff plant leaves from which symbolic shapes have been excised, and which have been arranged around the entrance to the spider’s burrow. The practice of Nggam is premised on an ethics of care and respect: between the human community, the diviner and the ground-dwelling spider whose wisdom is consulted. Spiders are consulted for certain decisions regarding the village, acting as a sort of tribunal. I am working now with the Cameroonian spider diviner Bollo Pierre and Oxford anthropologist David Zeitlyn on a project for Berliner Festspiele as part of the programme series Immersion at Gropius Bau, Berlin. I believe that in the context of mass extinction we are currently living in, we should be doing more of this, turning towards insects and spiders in order to better understand what many humans aren’t seeing in the world. We must take heed of these non-human intelligences.

Not only them, however. In many countries, indigenous communities are treated like non-humans and live on the fringe of society and the economy. Yet, though indigenous peoples only amount to approximately 6% of the global population, living a very intrinsic and deep relationship with the milieu that is surrounding them, the lands they manage support 80% of the world’s biodiversity. This means that, where humans are truly embedded in the web of life, biodiversity on the whole is in better shape. In Ecuador, as in many other places throughout the world, the richest biodiversity can be found precisely in those areas where a certain type of humanity is present and has managed to coexist with it. As we are currently witnessing the direct effects of zoonosis—infectious diseases caused by pathogens that have jumped from non-humans to humans—, it is important to consider that these spillovers are inseparably linked to biodiversity crises and destabilized ecosystems. Equilibrated cohabitation is a way to preserve diverse habitats; a way of living together which indigenous communities have been practicing for generations.

There is a huge need to acknowledge this, to strive towards a certain equality, and correct our values systems, addressing not only indigenous populations by the way but other growing social movements including Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. This is also why my upcoming augmented reality artwork “Webs of Life”, on the Acute Art app as part of Back to Earth at Serpentine this summer, will donate proceeds from the sale of the AR sculptures Maratus speciosus and Bagheera kiplingi to Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), a non-profit that connects with communities in northern Argentina that work to maintain biodiversity in their region. This project is an experiment in biodiversity and technodiversity that I’ve worked on with the research group Arachnophilia that I helped to found in 2018.

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel: The fundamental point for me is to understand that we are inheriting what might be considered the “Great Divide,” which is the fact that humans, in order to feel secure and comfortable within this world, have developed systems to separate, divide, categorize, and break relationships, interdependencies, ecosystems, vital needs and copresences, and solidarities. We are inheriting a very violent culture of authority and mastership that has transformed the Earth into a resource that can be endlessly exploited in order to feed our own profit motives and desires. Everything that derives from this culture—exhibitions included— expresses some form of violence. We shouldn’t ignore the fact that exhibitions are a very recent ritual for humanity, and are only a few centuries old. They derive from the “cabinets of curiosities,” which themself derive from the act of colonization. Bringing back objects from expeditions or trophies, for example, would historically be described as curiosity, but can now also be viewed as an act of appropriation, a way of taking possession of whatever had been encountered. Since around the end of the nineteeth century and beginning of the twentieth century, exhibitions have traditionally been based on the supremacy of the visual senses, meaning that, basically, our encounter with art mostly derives from the way we look at still objects.

As a curator, I must ask myself how we can invent new rituals for a new century. One of the options is to accept the aleatory, accidents, and porosity. In other words, to accept something that I’ve been describing lately as an exposition de catastrophe (disaster exhibition), a term inspired by disaster medicine, which is a discipline that forces practitioners to step out of their comfort zone, and be inventive while accepting their limitations. Similarly, artists need to accept the boundaries of their desires and the impossibility of bringing them into existence. Exhibitions are one of the most controlled rituals, for example. There are opening hours, and you follow a top-down curated experience, a specific, predefined route through an exhibition of artworks hung on walls. You have all a discourse around the works, and the visitor is asked not to scream or even speak, to be very discreet, to keep a certain distance, and all of this extremely authoritarian choreography is rooted in this idea of categories and separation. What I’m trying to do with exhibitions is to work out how to create a space that allows the outside to come inside, in order to transform the rules of the game, or to try to imagine new modes of presence for the visitors. This provides for new modes of encountering art, while allowing participants to behave differently, and to be much less authoritarian towards the experience.

Another way to try to overcome this situation is to invite people who do not call themselves artists into the process. The first time I worked with Tomás Saraceno was actually for Le Bord des Mondes [At the Edge of the Worlds], an exhibition where I was following the lead of Marcel Duchamp’s 1913 famous question on whether we could make works of art that are not art. I travelled the world for two years trying to find highly unique creators that were not necessarily calling themselves artists but who were producing ambivalent, ambiguous, poetic, inspiring works that I felt truly deserved more exposure, and I felt we almost had a duty to acknowledge as art. I invited twentyfive creators, and out of those, Tomás was the only one who was rather wellknown. To me, Tomás has always been an artist who has been between worlds and growing in the space between. His work with spiders, which is the one that I showed, has this ambiguity of the authorship in terms of who holds the pen and holds the creation.

The whole project was about the idea of transcending these inherited categories that I felt were becoming more and more inconsequential and irrelevant. I believe one cannot dictate where creation starts and stops. I wanted to acknowledge the fact that creation and art is such a large and vast territory that you cannot try to conciliate it into one space, one territory. In this exhibition for example, there were people that would traditionally be described as scientists, as researchers, or engineers, and still others that don’t fit any clear or defined category. The exhibition was working hard to erase this idea of “outsider artist,” or «art brut,» which is a category that I truly despise as it is rooted in a history of violence and coercion, the dictating of who is at the center and who is at the margins, and who holds and bestows legitimacy and upon whom. Categorization of this nature can be very judgemental and can be a very dangerous way to separate and classify humans. Also I really wanted to highlight the fact that doing so is much less interesting than trying to grasp the full complexity of the world. What I propose is instead to approach things from a child-like attitude where every sign, color, sound, and so on, is welcomed and accepted and reinforces life as an experience. Since then I’ve always invited creators who are working at the margins. In every show or group exhibition that I do, I invite creators who don’t need to hold the title of “artist” to produce incredibly challenging work and create new knowledge. The main challenge of our times is to unlearn, to undo, to de-articulate, to understand, to criticize, to scrutinize every method of seeing and feeling and sensing the world that we have inherited as Western Europeans. Once we will have deconstructed and reconstructed new discourses, new myths, and new narratives about how we can inhabit the world, then each one of us as humans will be able to start exploring beyond traditional absolutes. Artists have a crucial role to play in that regard, preparing the groundwork for the transformation of our societies. I think they can really deeply transform the way we think about economies, politics, society, urbanism, architecture… And Tomás has been incredibly involved in these sorts of processes because he has an incredible talent to go for every type of knowledge, to build bridges between worlds that we have been taught to think that they have nothing to say to each other, and to suspend his judgement.

Can you explain how the Aerocene could concretely help us escape from the Anthropocene?

Tomas Saraceno: I wouldn’t say the end aim is to escape from the Anthropocene, because our utopia and our ethics are more concerned with breaking free from the great narrative of divides, following Bruno Latour’s clear vision. The Aerocene Pacha balloon lifts off because we understood how to make the earth and the sun work together, rather than keeping them separate, but also because we collaborated with a population that has never divided in the way we divide, for which there is no duality between nature and society. We must keep learning from them. This is the idea behind the notion of “Pacha” by the way. Not “Pacha Mama,” which is Mother Earth or Gaia, but the concept of space and time and cosmos as an entangled web of life. Rather than fixating on a form of “escapism,” we focus on trying to somehow weave all the possibilities that we have today on Earth. Buckminster Fuller talked about “Spaceship Earth,” but this stems from a very mechanistic representation of this whole. I feel closer to the vision of Mother Earth, which is less mechanistic, that insists more on care and interrelationships.

A simple way of explaining the Aerocene is to say that I live a substantial part of my day, say 90%, in the Anthropocene, because my way of life, the objects I use, somehow belong to that era, but in the other 10% are those moments I feel proud of my behavior and am starting to live in another era. I don’t eat any meat, I change my diet, I look more around myself, and gradually am establishing a whole set of rules. Every day, I’m trying to gain one extra minute living in this alternative way of life. It’s a slow transition of sorts. Naming things, talking about the Aerocene, helps support this change, helps us represent it. I can tell myself that today, I’ve lived two hours in the Aerocene and so, hopefully, in the future, we will all start living in another era, and this era will start manifesting itself as a global phenomenon.

When Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel and I met to discuss her invitation to Le Bord des Mondes, it was understood that by thinking together against the inherited categorizations of the Anthropocene we could affect this transition a little further. The title of the group exhibition is key—not a single world but a plurality of worlds, emerging from all different backgrounds and environments. So, rather than transcending the Anthropocene or negating it, we exposed its limits in asking nonhuman models of social architecture, like spiders/webs, to guide our investigations. If the web of the spider is not simply its home, not simply its world but an extension of its body and mind, what could spiders/ webs teach us about the limits in our thinking, the limits of our worlds?

Le Bord des Mondes allowed us to pose a question and leave it floating in the air. This important collaboration with Rebecca would lead to On Air at the Palais de Tokyo three year later in 2018, where we came back together as an ecosystem of writers, artists, researchers, spiders/webs, cosmic dust and the very particles floating in the air we breathe. This was a space for listening and for some of the voices which go unheard by human ears to be amplified, emphasizing new forms of knowledge and knowledge production to counter the constant, growing threats of air pollution and lithium extraction. Each of us recognizes the urgency of the moment—we need new forums, new communities and new types of awareness for diverse, habitable, sustainable futures. The next step is to act on this feeling, to which the Aerocene is fundamentally both a response and a promise.

The Aerocene extends into all aspects of life. It is a large cross-disciplinary community of artists, researchers, and concerned citizens looking for new collaborations with the environment and the atmosphere, for new imaginaries and ways of life. When we organize gatherings of Aerocene groups somewhere in the world, members give themselves new rules and objectives: forbidding themselves to fly there, perhaps only taking trains and then being fetched at the railway station by someone riding a tandem bicycle, or perhaps, worstcase, sharing a car with other people. Perhaps all the food we eat is rescue food, we partner with Helen Eckstein of FoodSharing.de, a nonprofit that salvages food that has been thrown away, and we prepare it together… We are continuously inventing new rules, but the idea isn’t behaving like the thought police, dictating what people should be doing, but rather giving ourselves a code to collaborate and progress together. Group psychology can be of tremendous help, and so we try to grow these enthusiasms by sharing our desire to do better together and acknowledging that we are all trying to do things better.